From 14.12.2000

In 2000, The National Gallery of Greece celebrated 100 years in existence. This historic anniversary, which coincided with the celebrations for the millennium, was punctuated by the grand opening of the new display of the permanent collections, in the buildings refurbished through the generous sponsorship of the Stavros S. Niarchos Foundation.

The interiors were renovated according to an aesthetic which combined luxurious materials, minimalistic approach and emphasis on functionality. The design of the fixed panels on a triangular arrangement which adds dynamism to the elongated rooms was very highly regarded. The architectural studies for the renovation and the new display were both made by the professors Panos Tzonos, Sonia Haralambidou-Divani and Giorgos Parmenidis, in cooperation with the architects Irene Haralambidou and Christine Longuépée.

The permanent collections went on display from a modern museological pointview, in tune with the parallel development of art and society. The Director, Marina Lambraki-Plaka, professor of the History of Art, was tasked with the study for the new display. The study was supervised by Dr. Olga Mentzafou-Polyzou, Curator, National Gallery of Greece, now Director of Collections and Museum Planning, in cooperation with the curators Efi Agathonikou, Dr. Tonia Giannoudaki and Dr. Maria Katsanaki. Zina Kaloudi, Loula Kalaberidou and Roula Spanoudi conducted research in the museum storage rooms. The Chief Conservator, Dr. Michalis Doulgeridis, and his associates, prepared the artworks for the new display. Stavros Psiroukis was the photographer.

The new display concept.

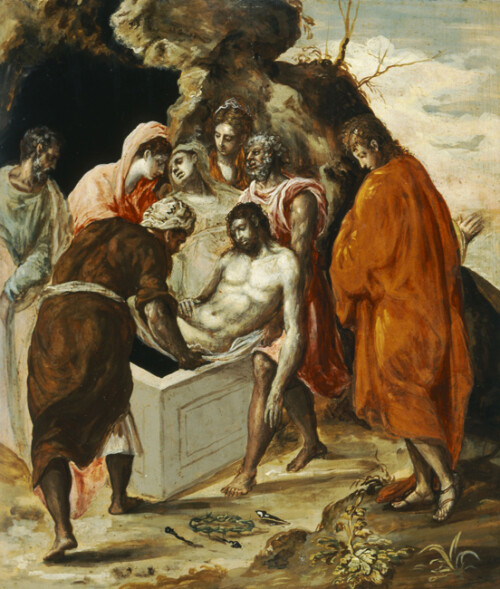

In the commemorative edition National Gallery 100 years, Four Centuries of Greek Art, we discussed our proposal in terms of the grouping and the display of the artworks. The works themselves, as well as the horizon of reception for which they were created, were our guide, rather than the methodological patterns already produced by historical research in Modern Greek art.

Due to historical circumstances, Modern Greek art has not followed an organic path of development. Therefore, it would not be correct to display the permanent collections according to strict art historical standards, as is the case in other European museums. The display of this material is expected to serve multiple goals. Key among them is, at least as far as the early period of Independence is concerned, to illuminate the role of art in the newly-established state and highlight the dialectical relationship between art and society. Accordingly, we sought to identify the dominant themes in response to a specific expectation horizon during each period. Therefore, as regards the early post-Independence years of King Otto’s reign (1832-1862), we recognized the principal ideological role played by historical painting: The promotion, idealization and monumentalization of the War was a pressing, existential need for the young state. Early Greek portraiture evokes the image of the emerging Greek bourgeois class, the traces of its agricultural past still evident. Early Greek landscape painting proposes an idealized image of Greece, populated by ancient ruins and bathed in the timeless light of romantic longing. Stylistically, Academism eradicated all other influences and sources of inspiration, for the level of the receivers of this art (expectation horizon) prevailed over centres of influence.

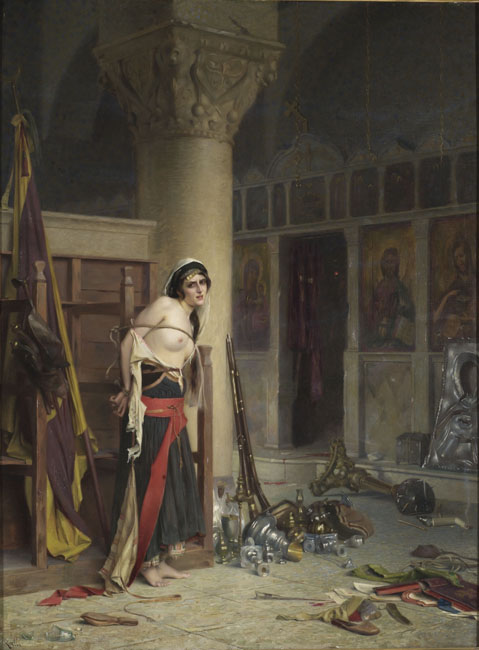

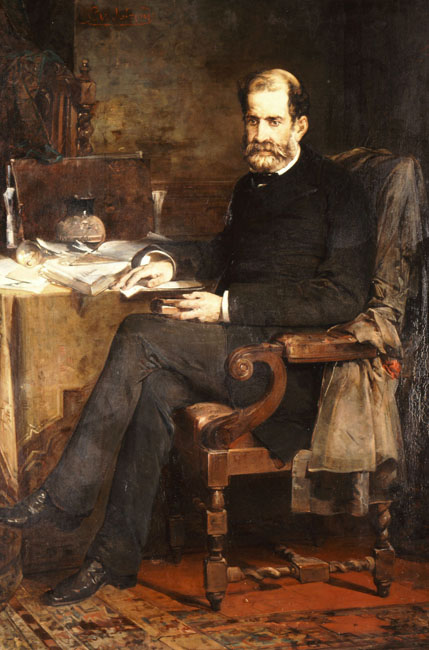

In the latter half of the 19th century (1862-1900), which coincides with the maturation of the bourgeois class and the domination of the Munich School and its great masters, the prevailing themes changed. The place of historical painting was now taken by genre painting, in various nuances (Orientalism, etc.) and schools (Munich, Paris). Genre painting, an idealized derivative of realism, shelters the longing of the bourgeois class, its false paradise. Haute-bourgeois portraiture, staged within emblematic surroundings, was radically different from the staged portraits of the early period. Still-life painting celebrates the material wealth of the new social class. Landscape painting ceased to see the world through the eyes of romantic travellers: it became realistic, set en-plein-air, feeling the first inklings of Impressionism. A special section is dedicated to Gyzis’s symbolist period. Alongside his idealistic vision the artist liberated his technique, thus becoming a great European master of the end of the century.

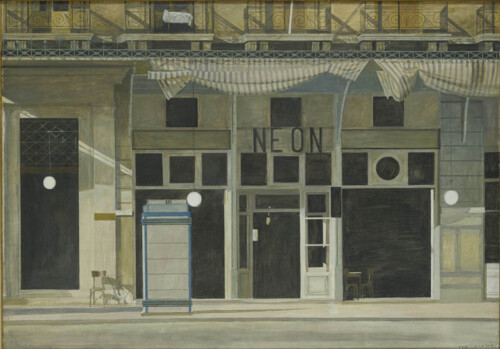

The 20th century saw a turn towards a new political, social and artistic reality. The Modern Greek modernism became en-plein-air painting. The new hierarchy now brought to the foreground post-impressionist concerns, accompanied by an ideological, rather than merely aesthetic demand: to capture the Greek light in colour (Greek light and colour). Besides, the Greek-centred ideology became an almost permanent feature of the rhetoric which developed around artistic creativity in Greece, encouraged by historical reasons, such as the Asia Minor Catastrophe in 1922.

The year 1922 was a turning point for Modern Greek art of the interwar period. The national humiliation over the Asia Minor Catastrophe was the pretext for a fall back that reflected the post World War I return to order and tradition, characteristic also of European art. The title of this section is: from sense to intellect. After a short flirt with en-plein-air painting from life, Greek artists, led by Konstantinos Parthenis, turned to an inner, cerebral image. This shift, accompanied by a return to anthropocentrism, led to various directions. Painters now sought inspiration in both tradition and modernism. These currents crystallized into the Generation of the 1930s. A restless, sceptical generation, extrovert (closely following European developments) as much as introvert (discovering another kind of tradition through the teaching of modern art).

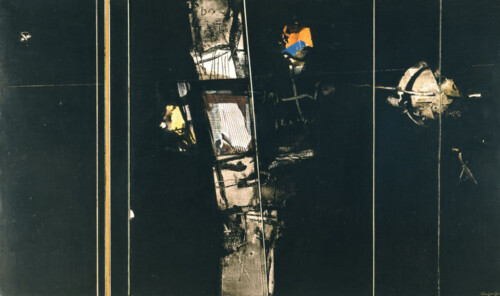

The post-war generation is one of successors, who continued the legacy of the Generation of the 1930s. This does not mean that no great and original artists were members of that generation. In the mid-1950s, Greek art kept up the pace with the new abstract trends in Europe and America. The 1960s witnessed the mass migration of Greek artists to major European art centres. These artists took an active part in avant-garde movements, thus breaking free from the isolation that kept Greek art confined within national borders. From then on, Greek painting went hand in hand with international pursuits without losing track of its indigenous identity. Space considerations do not permit a lengthy discussion of the recent currents in Greek art. For this reason, long-term temporary exhibitions will be held in the space dedicated to contemporary art.

This discussion of the National Gallery’s permanent collections creates the need to pay our respects to all those who worked for one century so that we may enjoy a complete overview of Modern Greek art today. We feel it is our obligation to honour our predecessors, the directors of the National Gallery of Greece, from the first Director, Georgios Iakovidis, also Director of the Athens School of Fine Arts, and Zacharias Papantoniou to Marinos Kalligas and Dimitris Papastamos. It is only through their struggles, their efforts, their administrative and scientific organization of the museum and inspired acquisitions, that the National Gallery of Greece came into existence.

Sponsor: Stavros S. Niarchos Foundation

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20