A salute to the suffering people of Italy, especially the citizens of Milan,

the city that hosts these masterpieces,

housed in the famous Pinacoteca di Brera.

May Easter bring hope and salvation to all humanity.

Marina Lambraki Plaka

Director

Giovanni Bellini and Andrea Mantegna

Two Renaissance depictions of the Passion of Christ

I still cannot forget the powerful emotional impact it had on me when I first looked at the Dead Christ by Andrea Mantegna (about 1431–1506) in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. Many years have passed, yet my feeling remains. Every time I find myself in this northern Italian city, I visit the Pinacoteca to pay homage to this gripping depiction of human suffering. Nor do I fail to stop before another, equally riveting, painting nearby, on the same theme: the Pietà by Giovanni Bellini (about 1435–1516).

Both artists and artworks are closely linked. Mantegna had joined the distinguished Venetian family of artists by his marriage to Giovanni Bellini’s sister, Nicolosia. The two prominent artists shared their experiences and influenced each other. Mantegna’s incisive drawing style, which brings his figures into sharp focus, as if they had been engraved in copper, for a while ensnared in its magic the tender Giovanni – the artist who went on to introduce the graceful, atmospheric style of the School of Venice, to become Giorgione and Titian’s master.

Related artists, kindred works. Both were executed in tempera, but Mantegna’s Dead Christ was painted on canvas, not panel, a material fit for this, still Medieval, technique, to which Giovanni Bellini adheres more closely. The Venetian artist’s Pietà (c.1460) betrays his debt to Mantegna. Both paintings exhibit a razor-sharp accuracy and similar palette. Yet, this is where the similarities end.

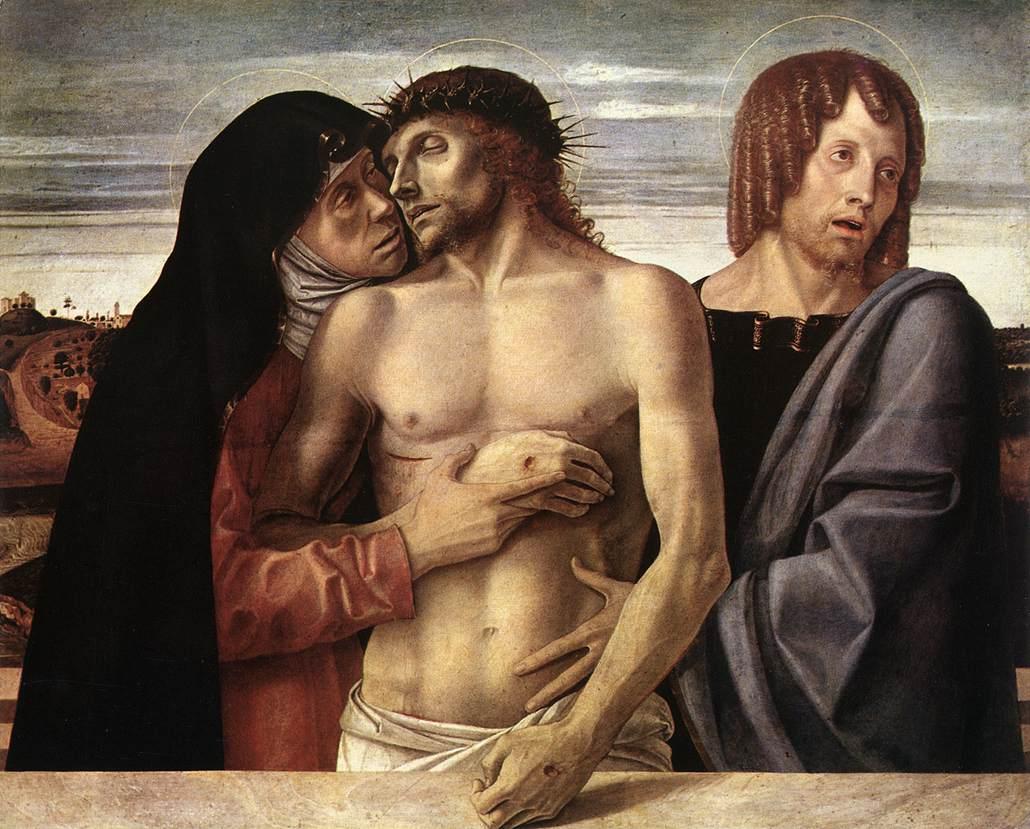

Despite its pathos, the Pietà by Giovanni Bellini is classical. The three holy figures – the dead Christ, the Virgin Mary, and Saint John – still possess a classical beauty, in spite of the pain that shakes them. The frontal arrangement of the figures and the marble parapet at the bottom create a shallow composition, in accordance with the classical rules. Christ’s face is contorted in pain, the mouth half-open, the eyes sunken as he leans to rest on his mother’s cheek, which is hollowed out by grief. Mary’s strong hand presses Christ’s lifeless hand on a body that seems to have been styled after ancient statues. The Saviour’s left hand rests inertly on the marble sill, casting a shadow that makes it appear to be very close to the actual space. The wounds suffered during the crucifixion intensify the viewer’s immersion in the Passion of Christ. The Latin inscription accompanying the artist’s signature indicates his intention to elicit powerful emotions in the faithful: ‘Every time these tear-swollen eyes will provoke sobs, perhaps it will be Giovanni Bellini’s painting that is weeping.’

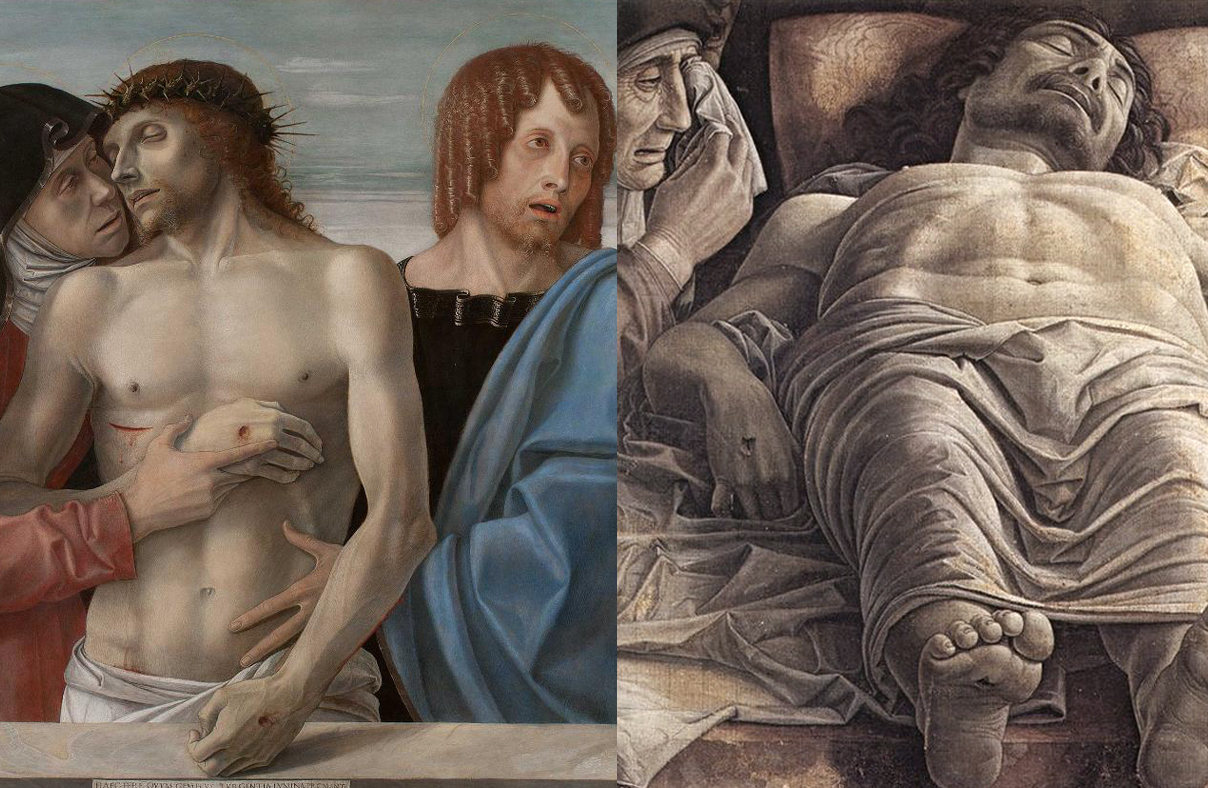

Mantegna’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ (1483) does not share this classical sentiment. In this work, naturalism and scientific spirit, characteristic of artistic pursuits in the Quattrocento, are united in a composition of superb dramatic tension. The figure model is a mature male, utterly bereft of divinity – a labourer, one might say with anachronistic boldness, despite the halo around the heavy, square head. Christ’s athletic body is laid out on a slab of red-veined marble – a reference, it has been noted, to the holy relic of the Stone of Unction, kept in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople until the city’s fall to the Turks in 1453. This slab, ‘ingrained with the Virgin’s white tears,’ was where the body of Christ was laid upon after being taken down from the cross to be embalmed by Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea. In Mantegna’s painting, the myrrh container can be seen placed on the slab beside Christ’s head. The marble slab had been transported to Constantinople during the reign of Manuel I Komnenos in the 12th century from Ephesus, where, according to tradition, it had been brought by Mary Magdalene. The image of the Stone of Unction has been identified by scholars in Byzantine representations, including the 12th-century gold-embroidered epitaphios in the St Marc’s Museum in Venice.

The beholder sees the recumbent body of Christ from a totally unexpected perspective, foregrounding the open wounds on the soles of his tortured feet, which protrude from the slab, extending out of the painting into the viewer’s space. Covered in pale green-tinged white drapery, which resonates with the pallid hue of death, the body of Christ is depicted in steep foreshortening. At first glance, the painting seems to present an accurate perspective. Yet, rather than being presented at a smaller scale due to taking up a smaller portion of our field of view, the head and torso are enlarged to reflect their importance. The image is reminiscent of a reclining human figure seen from a distance through a telephoto lens. Still, the corrections made by the artist cannot be accounted for by geometric perspective. A true religion for Renaissance artists, perspective nevertheless never restricted them. On the contrary, from the moment Brunelleschi and Alberti discovered it, in the early Quattrocento (15th century), artists adapted it for their own creative purposes. In the Brera Dead Christ, Mantegna used perspective to achieve a bursting intensity in his depiction of the Passion. Portrayed in uncompromising realism in the far left, the three mourners – the Virgin, Saint John, and Mary Magdalene – accentuate the human aspects of the Passion of Christ.

Marina Lambraki-Plaka

Professor of Art History

Director, National Gallery – Alexandros Soutsos Museum

English translation: Dimitris Saltabassis