This strange yet “modern” painting is the heavenly section of an “Annunciation”, today in the collections of a Madrid bank. It is one of the very last works painted by Greco shortly before he died in Toledo in 1614. Left unfinished, the painting teaches us a lot about the artist’s technique. One notices that these angels have no wings. They are the members of a heavenly orchestra, playing period musical instruments, of the sort that the artist must have seen while living in Venice. The instruments are a spinet (a precursor of the piano), a harp, a flute and a viola da gamba. The second angel is holding the score and directing as well as singing. Note the accuracy in capturing the musicians’ gestures. The figures have been rendered in swift brushwork, and the angels’ robes sway with movement, as if they were swirling tongues of fire. Note also the iridescent palette employed by the painter: the orange in red and green, the gold in blue. Changing even as the light falls on them, such colours were called metanthounta by ancient Greeks. The painting is vibrant with inner life. The Concert may be seen as a precursor of Expressionism.

“St Peter” belongs to a series of portraits of Christ and the Twelve Apostles which was first produced by El Greco, called “apostolados.” Such works frequently decorated the treasury in Catholic churches, where the sacred utensils of the church were kept.

“St Peter” is an austere, realistic figure, meditatively gazing beyond the viewer. He is holding in his hand the keys he was entrusted with by Christ. The blue robe and orange himation have been rendered in broad brush strokes; white lights run across the foldings like lightning, evoking the lights and golden trimmings in Byzantine art.

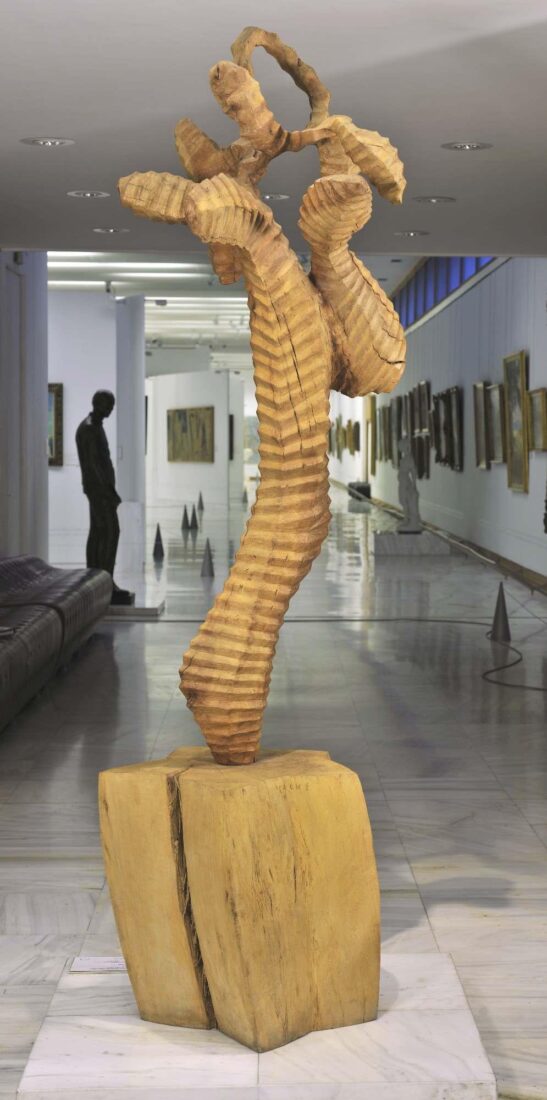

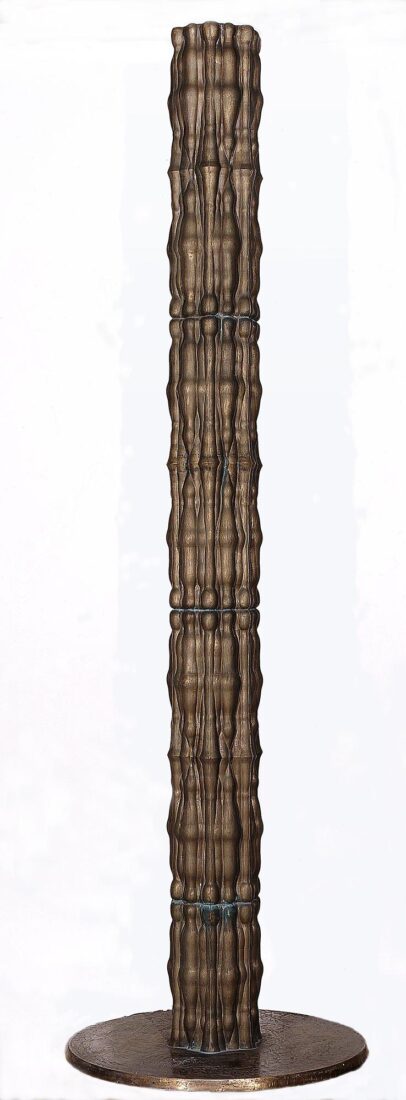

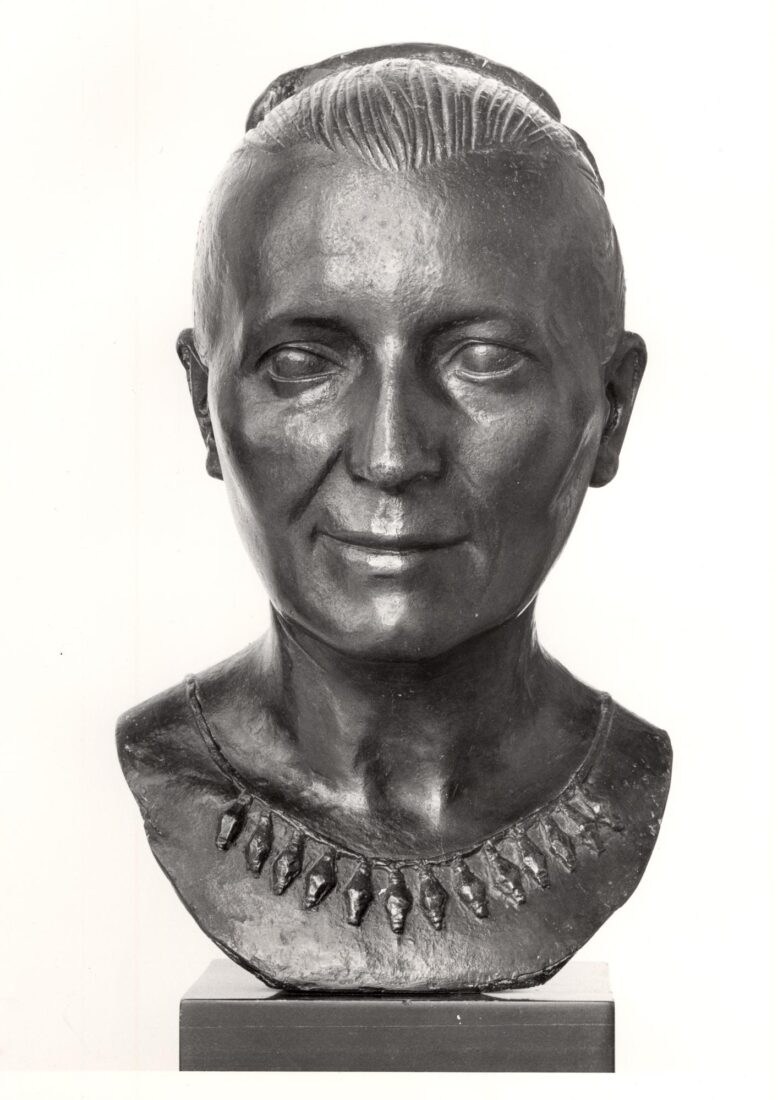

In 1918, 40 long years after the first manifestation of the symptoms of a deviating behaviour which led to the artist’s institutionalisation for 14 years, Yannoulis Chalepas’s second period as an artist began. During that time, Chalepas exhibited a totally different style: free and spontaneous, independent of academic training, guided by ancient Greek art. He now focused on the essence of each work, as he was not interested in detailed processing, refinement, or idealisation. His figures now became introverted (“St Barbara and Hermes“), solid and imposing (“Medea III“), almost hieratic at times (“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). He gives, using spare means, the tone in the pose or facial expression and transforms his works into psychographic portraits (“St Barbara and Hermes“,“Resting female figure“,“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). Moreover, several complementary elements, probably of an obscure symbolic meaning (“Medea III“), often add to the main theme and give a surreal tone to the work as a whole. The artist made clay models, not seeking a more finished version; he was engaged in several works at the same time. Not using an internal frame, he continued to make works inspired by the Greek antiquity and mythology (“St Barbara and Hermes“, “Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“, “Medea III“), figures inspired by the urban environment, or his village (“Harvester“, “Hunter“), female nudes (“Reclining female figure“, “Small reclining female figure“), different-scale figures combined, as well as his characteristic as much as hard to interpret works (“The secret“,“ The thought“, “St Barbara and Hermes“), selecting themes suggestive of his personal experiences.

Made in Venice, this work is representative of a particular phase in the artist’s development, that is, at a time when he sought to assimilate the teachings of the art of the Renaissance: the articulation of space in perspective, emphasised here by placing the marble sarcophagus on an angle and by the way the figures stand in space, as well as by the modelling of volumes through chiaroscuro and the shadows projecting against the ground. Of classical proportions, Christ’s body is depicted almost in the guise of an ancient statue. The profuse colour and dramatic expression culminating in the Virgin’s fainting are traits of the Venice Renaissance art. El Greco borrowed many elements in his composition from other Renaissance artists but so masterfully has he arranged them that this is hardly noticeable. The only elements reminding us of the Byzantine provenance of the painter’s art are the wood panel on which the painting is made and the medium of egg tempera, combined here with oil – a medium characteristic of the Italian, especially Venetian Renaissance.