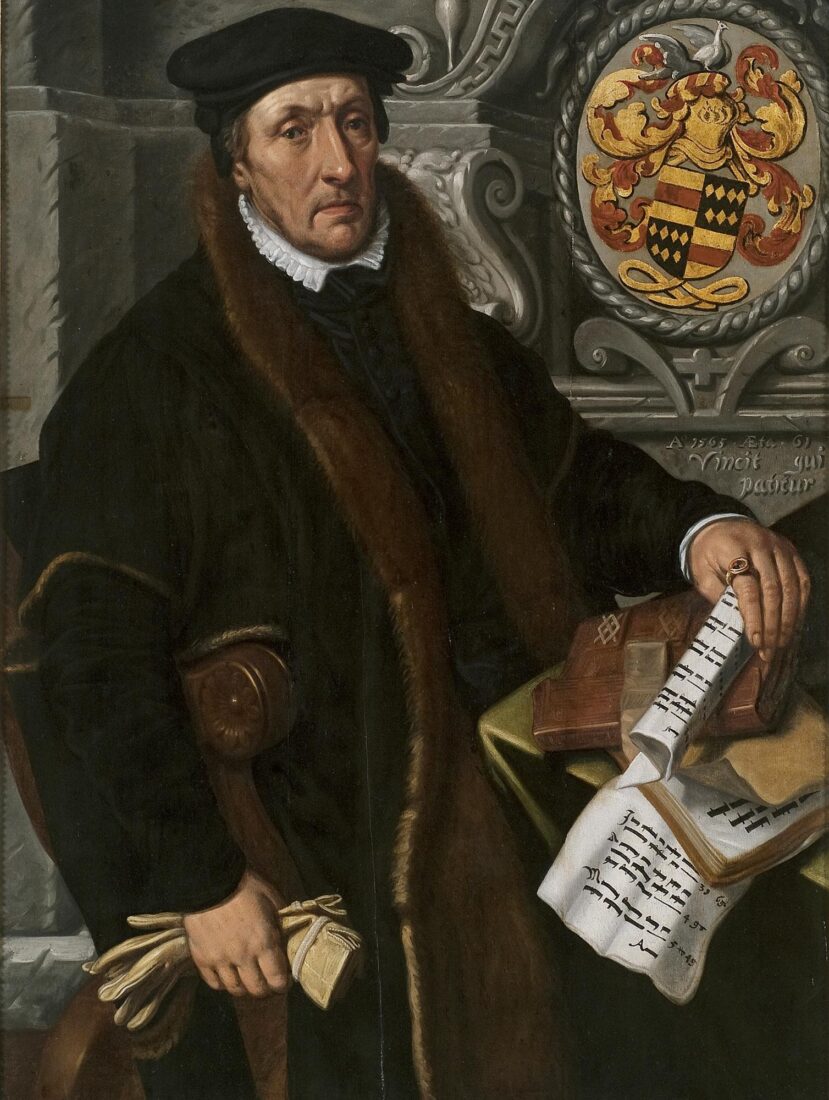

This work was purchased by the National Gallery in 1996, after it was presented at the exhibition “El Greco in Italy and Italian Art”. Despite the fact that the original attribution given in the exhibition catalogue was to Jacopo Tintoretto, it subsequently came into question, and the curator of the Western European collection at the time, Angela Tamvaki, decided, after considerable research, that the work should be attributed to his workshop; the work itself was still purchased, because of its quality. Furthermore, it is well-known that Tintoretto, trying to deal with the multitude of commissions he received, had put together a large workshop with many assistants and fellow workers, among whom were his sons Domenico and Marco, and his daughter Marietta.

In terms of style, the work is a characteristic example of Venetian painting from the second half of the 16th century. It is a diagonal composition dominated by a figure twisting and sweeping ahead. The light falls on the face and the body brilliantly and drenches the dark ends of the hair, which is held in place by a piece of gold jewellery decorated with precious gems at the back part of the head. The ornamentation of the figure is comleted by necklace and ear-rings, both of pearl. The overcoat, decorated with leaf designs, falls in undulations, creating movement in the saint’s otherwise devout attitude. The brushstroke is quick and broad. The figure itself is depicted without details while, conversely, the moulding of the flesh is more sensual. Despite its small size, the painting is characterized by the same monumental and sculptural temperament one finds in Tintoretto’s works.

Since this is a fragment of a larger composition, it is not certain if the depicted figure should be identified with this specific saint or not. The halo on her head and her devout attitude bear witness to the fact that this not a secular but rather a religious figure, and in keeping with the fashion of that period in Venice, she is depicted as an aristocrat, wearing resplendent garments.

Painted by Pablo Picasso (Malaga 1881 – Mougins 1973) in 1939, “Female Head” was donated by the artist to the Greek people in honour of its brave resistance during the Nazi occupation; it formed part of the French Artist’s Donation, made on the initiative of the Milliex couple in the aftermath of the War. It is a portrait of the photographer Dora Maar, Picasso’s companion between 1936 and 1943, as evidenced by the fact that this painting can be seen in a photograph by her from the studio at Royan, in 1940, where they retreated when Paris was occupied by the German army.

Dora Maar documented as a photographer the complete production process of the Guernica; her personality provided Picasso with the model for “the weeping woman”. Two and a half years after “Guernica”, the same attitude towards colour is noted in “Female Head”, conveying the pessimist mood prevalent during World War II.

“Psyche” (ca. 1880-1882) by the Victorian symbolist painter and sculptor George Frederic

Watts (London 1817 – 1904), is a gift of Alexandros K. Ionidis, a great collector of British society, as was his father, Konstantinos Ionidis-Iplixis, and a personal friend of the artist’s.

Psyche was a beautiful mortal maiden, and the goddess Aphrodite was so envious of her beauty that she sent her son Eros to poison with his arrows all men, preventing them from falling in love with her. Yet, Eros himself fell in love with her and, as Psyche being mortal was not permitted to face an immortal, he led her to a palace where he came to visit her only at night, in the dark, without her ever being able to see him. Yet, Psyche, full of curiosity about her obscure husband, one evening while he was sleeping took a lamp and went to see his face. She was astounded by Eros’s beauty and dropped oil from the lamp on him and woke him up. Angered by her curiosity, he left. In regret, she looked for him everywhere and, after many trials, with the help of Zeus, who made her immortal, reunited with Eros for ever.

In Watt’s work (a different version of the work in the Tate Gallery, inv. no. 1585), the only hints for the story of Psyche are the feather on her foot, the lamp fallen on the ground, and the bed in the background. On the contrary, the idealized “impersonal” slim and tall nude female figure personifies pure divine eros.

Ιn contrast to his Impressionist friends, Fantin-Latour evinced no inclination to work in the open air; he was a painter of the atelier. His early still life works, from the 1860s, were austere depictions of fruit and flowers. He frequently, as in the present painting, placed the table at an oblique angle, cutting off the corners, thus making the image more dynamic and worked it in a way that it was viewed from a slightly elevated angle. In the still life at the National Gallery, which is made up of flowers, most probably pelargoniums (flowers from the geranium family) and summer fruit, the objects are arranged lengthwise along two parallel lines formed in relationship to the table’s far corners; the vase placed behind the fruit is, in reality, the composition’s vertical axis. The white “spots” that represent the flowers, the plates and the sugar are set in contrast to the vivid colors of the fruit, the dark tone of the wood set against the tepid grey background. The melon sliced open and the fully-ripened strawberries arouse the sense of taste while the gleaming cherries, apparently freshly picked, and the sugar, encourage one to sample the fruit. The simplicity of this still life, austere but at the same time provocative, in terms of the sense of taste, is an example of a subtle quest, of an admirable blending of material, painting surface and shadow. The black vase and the table made of wood, with an exceptionally glossy polish, is often seen in this painter’s still life works with fruit and flowers which he did the same year (National Gallery, Washington D.C. and The Metropolitan Museum of New York).

Donated by Aikaterini Rodokanaki in 1907, “Madonna and Child and Saint John the Baptist in a Landscape” could be associated with a series of paintings dating from the late 1620s, painted after Jan Brueghel the Elder’s depictions of the Holy Family in an idyllic wooded landscape. In this painting, we can see the Virgin and Child, accompanied by Saint John the Baptist as a child; seven cupids carry baskets of flowers and fruit (week of 3 September). The scene is set in a heavenly landscape of flowers, trees, small animals (week of 7 September), and birds flying over a river on the left.

As was the case with his father, most of these religious works by Jan Brueghel the Younger were produced with the help of Hendrik van Balen I (Antwerp 1575 – Antwerp 1632), Brueghel’s permanent collaborator, who was tasked with painting the figures in such compositions.

The painting in the Evripidis Koutlidis Collection depicts the vernissage day at the Palais des Champs-Elysees, or Palace of Industry, built for the 1855 World Fair in competition with London’s Crystal Palace. The 1878 and 1889 World Fairs, the Salon from 1857 on, and other exhibitions, horse races, and other events were held there until its demolition in 1897 to make room for the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais, which would host the 1900 World Fair.

This is a group portrait surrounded by sculpture exhibits, featuring some of the most prominent artists of the Third Republic, including Bouguereau, Puvis de Chavannes, Bonnat, Gerome, Roll, Carolus Duran, Harpignies, and the author Alexandre Dumas. Sculptors Dalou and Rodin, alongside Gustave Larroumet, can be seen talking near Alfred Boucher’s sculpture “To the Finishing Line” (“Au But”). Ιn the foreground on the right can be seen Auguste Cain’s sculpture “A Tigress Feeding Her Cubs” (“Tigresse apportant un paon a ses petits”). To the right of the composition is depicted the artist and his wife.

This painting documents, not only the social and artistic life of the time, but also the building itself, as it preserves its architecture, famous for its iron construction. The scene takes place underneath the arched glass roof and before the iron interior and the imposing stained-glass window depicted in the background.

The still life at the National Gallery is one of the few signed and dated works by this artist. The work is an example of Linard’s first period. We see a wooden table, on which a pewter plate has been placed, set against a dark background, and on which are arranged peaches, plums and pears in a pyramidal configuration. The velvety and fleshy texture of the fruit, the cold feel emanating from the metal combined with the hard surface of the table, create the impression of a real scene. The composition is thus characterized by the harmonious blending of cold and warm colors and balanced shapes. The credibility of the image is further intensified by the piece of paper in the middle of the table on which the artist has signed and dated the work. The manner in which this is presented nailed on one side and slightly ripped from the second nail, that was supposed to hold it, as well as its detailed description is reminiscent of another kind of painting that also developed in the 17th century, namely trompe-l-oeil.

This charming portrait is a characteristic example of the painter’s work, especially popular during the era she lived in, when it became the fashion and was eagerly sought by European Courts and aristocratic circles. These attractive portraits are today viewed by some with a fair amount of irony because of their flimsy manner and superficial content, but they also mirrors, to a degree, the spirit of her time and they also constitute an original and purely Venetian form of creation.

Contrary to most of her predecessors and contemporaries, who were not specialized portrait painters, Carriera did specialize in this kind of work, one she was notably successful at. The beautiful woman depicted in this painting, with her ethereal charm and expressive glance, holding a mask in her hands, powerfully brings to mind the feel of the atmosphere of Venice and its inhabitants’ love of festivals, highlighted by their unique Carnival.

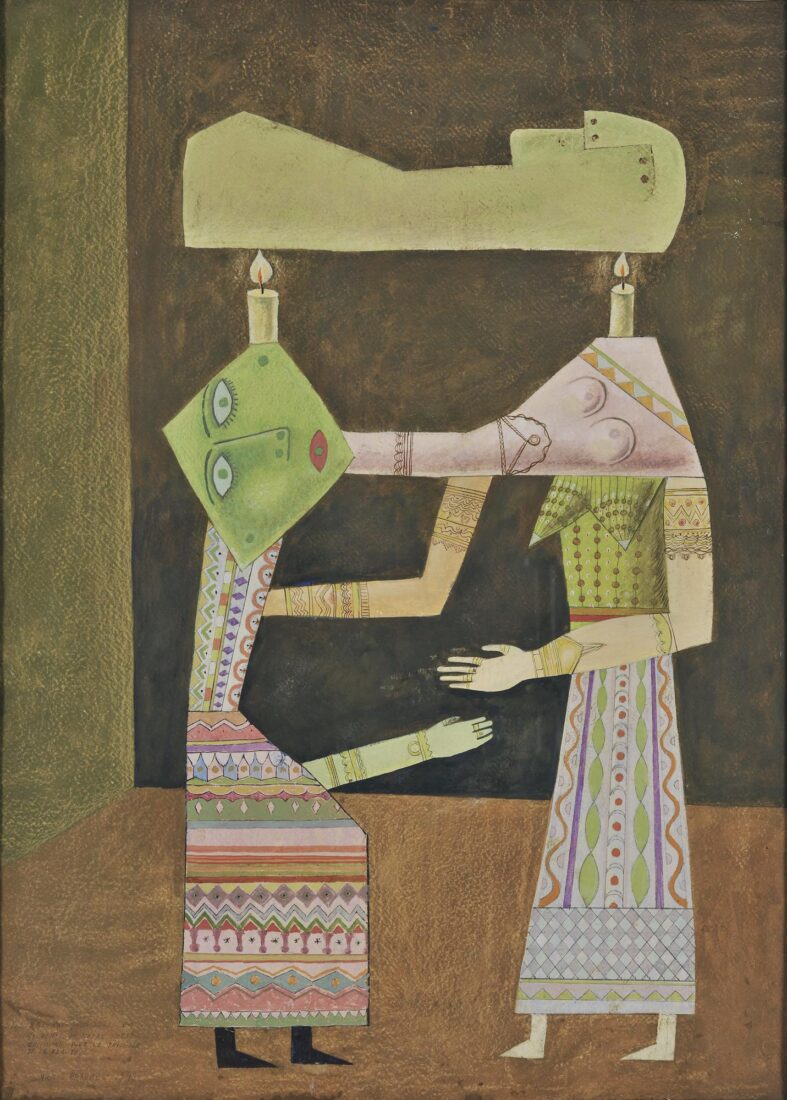

Brauner, surrealist painter, Romanian of Jewish origin sought in his images to reply to the question “What is the meaning of Being?” His overall outlook is based on Empedocles’ On Nature, according to which heads without a neck, arms without shoulders, and eyes without a face wandered on earth, until two superior laws, Love and Hate, collected these haphazard pieces and composed either monsters or divine creatures. In Brauner’s work, these creatures sometimes keep a different self, often a heterogeneous one – of a different sex, or a different kind of species – hidden within themselves, or seek one, with which to unite.

Employing the language of symbols of his religion, or of other ethnic religions (such as those of South America), of Mexican or Indian art, the artist provides the key for deciphering his images