Chalepas Yannoulis (1851 - 1938)

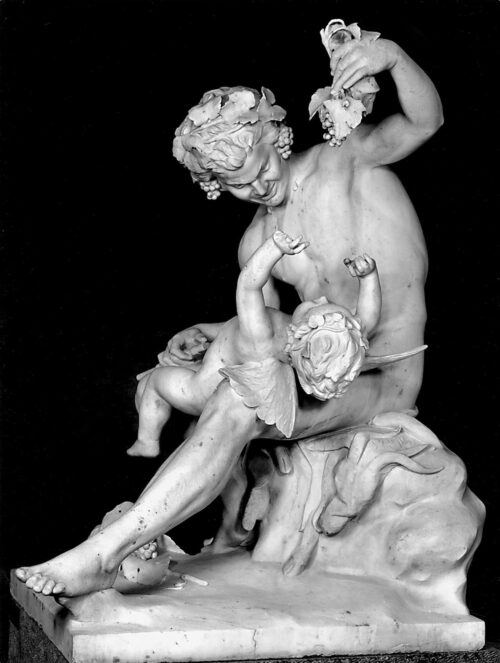

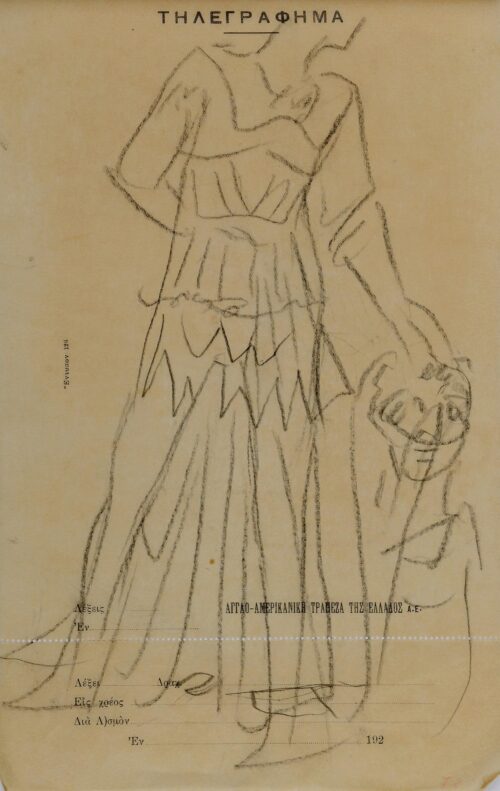

Satyr Playing with Eros, 1877

His family had a tradition in marble working, since both his uncle and his father, Ioannis Chalepas, decorated churches and built funerary monuments. Yannoulis’ talent expressed itself at a very early age, but as soon as he finished grammar school his father sent him to Syros, to work for a merchant. After intense disputes his family moved to Athens in 1869. Yannoulis enrolled in the School of Arts and studied under the superb neoclassical-style sculptor Leonidas Drosis until 1872. His exceptional talent enabled him to finish the School in half the required time, while he won all the prizes in the various contests there. In 1873, on a scholarship from the Holy Evangelistria Foundation of Tinos he went to Munich and continued his studies at the Academy there under Max von Widnmann. The distinctions and prizes kept on coming and he seemed destined for a brilliant career. But in 1875, for unknown reasons and despite the endeavors and the remonstrations of his professors, his scholarship was cut off. He managed to remain in Munich for a while, assisted by his friend the subsequent well-known historian G. Konstantinidis. In 1876 he was forced to return once and for all to Athens where he opened his own workshop. During this period he made two of the most important works of the first stage of his artistic career: “Satyr Playing with Eros” (1877), for the model of which he won the gold medal at the Munich exhibition in 1875, and “Sleeping Female Figure” (1878), for the tomb of Sofia Afentaki in the First Cemetery of Athens. These works are characterized by the exceptional way in which the doctrines of neoclassicism are used.

In 1878 he showed the first symptoms of mental illness. This disease, which is inherited, according to certain researchers, was either due to heartbreak or was a manifestation of his exceptionally sensitive psyche. Because of this, his work came to a halt for forty entire years, and he was committed to the Mental Hospital of Corfu in 1888 diagnosed with dementia. In 1902, after the death of his father, his mother, who had always been opposed to his commitment, took him out of the Mental Hospital and brought him back to Tinos.

It is not known if during the many years that followed, he worked or not, even if only in the most rudimentary ways. A tiny head of a male figure in clay, which he made in the Mental Hospital, and is the only thing to survive from that time, shows that he had not completely lost his creative drive. This figure, completely unornamented, with a nearly featureless face and in part deformed, may represent a kind of tragic self-portrait.

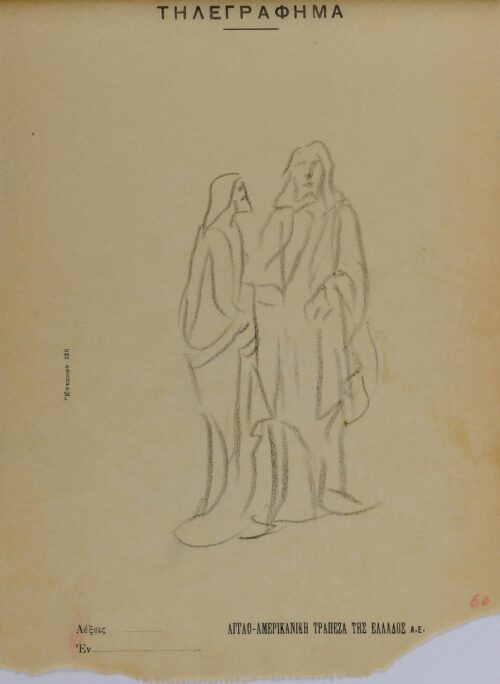

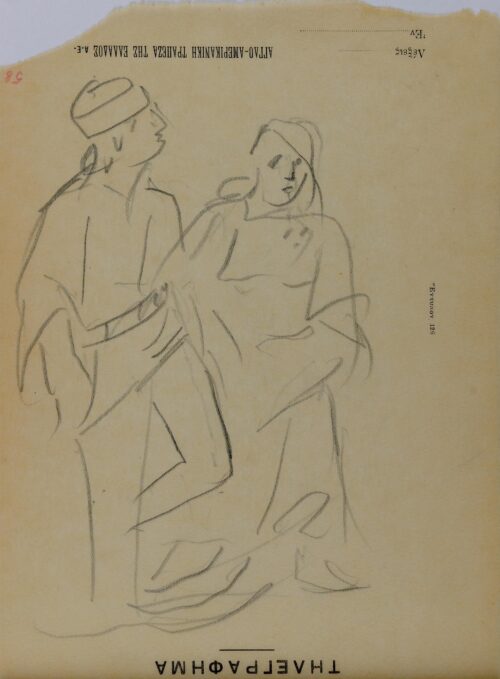

During the period which followed, Chalepas, closed within himself, and in terrible distress, was kept under his mother’s strict supervision; she destroyed the works he made in clay, as she was of the opinion sculpture was responsible for his illness. In 1915 Theοdoros Vellianitis, through a series of his articles in the newspaper Αθήναι, managed to create a little stir in regard to this forgotten sculptor, but it quickly died down. The death of his mother in 1916 appears to have been decisive.The artist, undistracted at last, became to work intensively, creating, by the time of his death, a significant number of works, but which all remained at the level of clay models. During this phase of his work, he did not use any kind of framing, as he wanted to express himself with absolute freedom, for a frame would have imposed a specific outline and prevented any significant changes being made. Several of these compositions were later cast in plaster, but they never acquired the completed form of a finished work of art.

During this second stage of his creative career, he expressed himself in a completely different style, instinctually and spontaneously, which had its sources in its inner anxieties and expressed his personal experiences. And despite the fact that for years he had been cut off from the developments taking place in both Greek and European sculpture, his works often are oddly in tune with the avant garde quests to be encountered in expressionism, cubism and surrealism. Greek antiquity continues to be his main source of inspiration, while at the same time he elaborated on compositions that had been begun before the onset of his illness. Characteristic is “Medea” which he reworked a total of four times and “Satyr Playing with Eros”, which he reworked twelve times. For these two works in particular, the hypothesis has been formulated that they suggest the relationship of Chalepas with his parents and the role each of them played in the development of his life.

The form of the reclining female figure, alone or in combination with other figures, is another theme which frequently occupied him and it too may be of symbolic meaning.

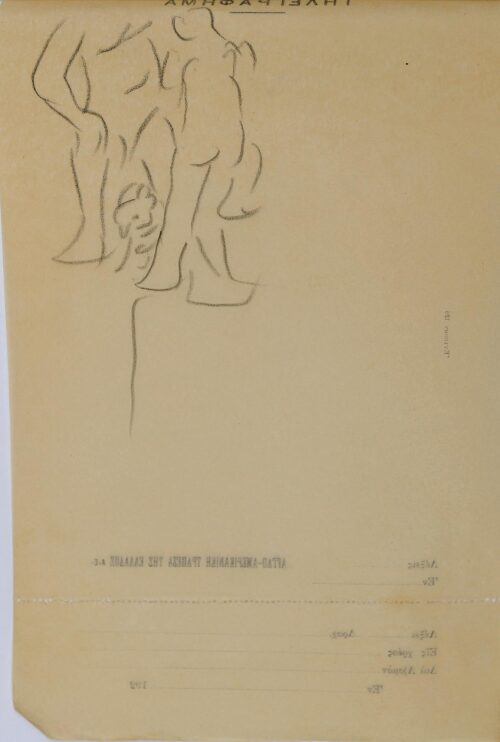

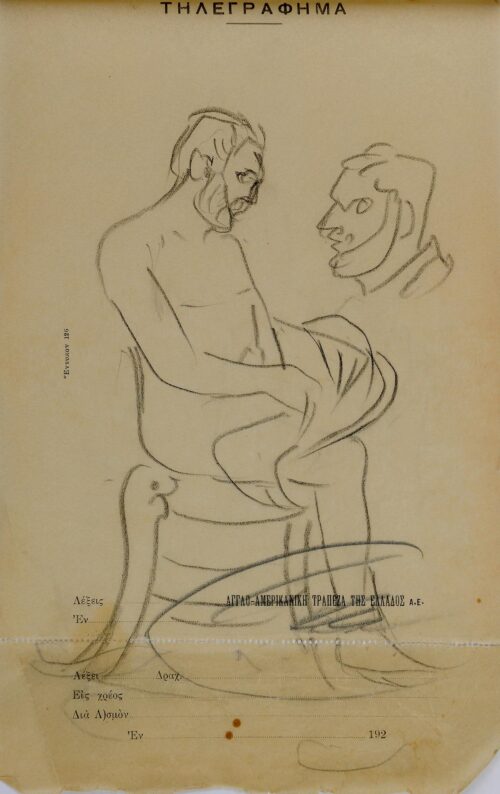

Characteristic of this second stage of his career are the “double-fronted” works. In these compositions two different, heterogeneous figures, the one frequently made as a bust and the other full-figured, coexist in an antithetical state. And though some of them are referred to by various descriptive titles, they in fact combine figures of Greek antiquity and the Christian religion. Chalepas himself said that his intention here had been to show the links of the old religion with the new, but it would seem that there is symbolism hidden here as well, derived from his own personal experiences. And indeed, the experiences of the artist are quite obviously suggested in certain of his works from this second stage, in which the expression on the depicted figures reveals inner pain and the sense of being forsaken.

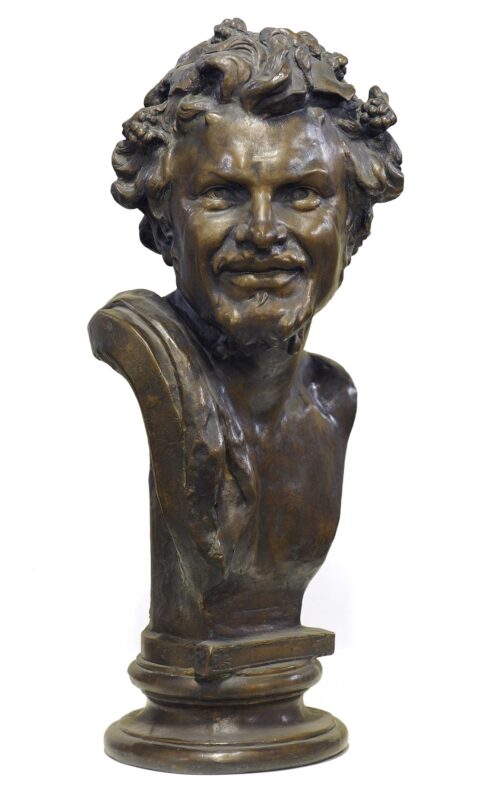

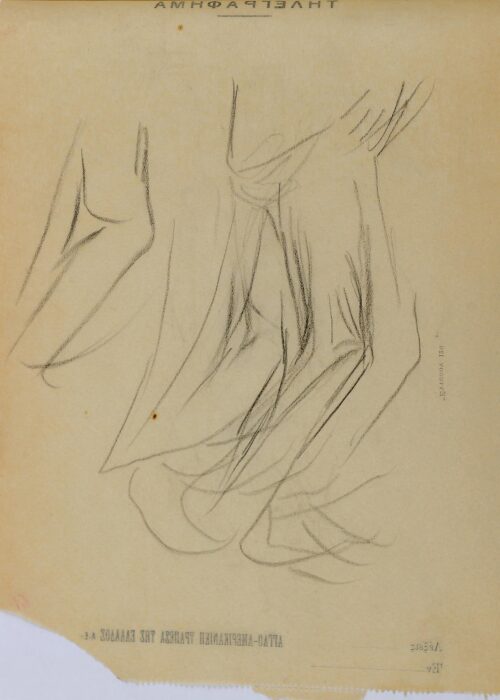

From this period of his career a significant number of drawings survive as well; many of these have been done in the account books of his father’ s business. In these drawings, sketched on top of each other, there can be seen the preparation of a work, the course it takes and its completion or even the solutions that in the end were not used. Characteristic of this is the fact that a number of them use the symbols found on decks of cards, the spade and the club, which symbolize, though discreetly, the male of female sex, while in other his self-portrait coexists with some other depictions, apparently unrelated.

The peculiar course that Chalepas’ life took did not, naturally enough, allow for much exhibition activity. After the endeavors of Theodoros Vellianitis in 1915, he remained in oblivion until 1922 when Thomas Thomopoulos visitεd him on Tinos and contributed to the organization of his first exhibition at the Athens Academy in 1925, with works cast in plaster. A second exhibition was presented by N. Velmos in 1928 at the Art Asylum, while a year earlier he had been awarded the High Distinction in Arts and Letters. After his death his work was presented in numerous retrospectives. In 1930 his niece Eirene took him with her to Athens where he lived for the final eight years of his life in familial tranquility, continuing to work intensively until his death.

Satyr Playing with Eros, 1877

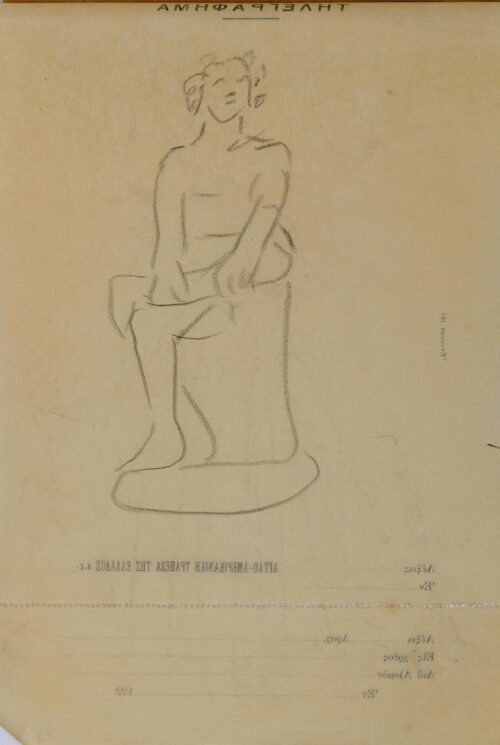

Aphrodite, 1931

The Thought, 1933

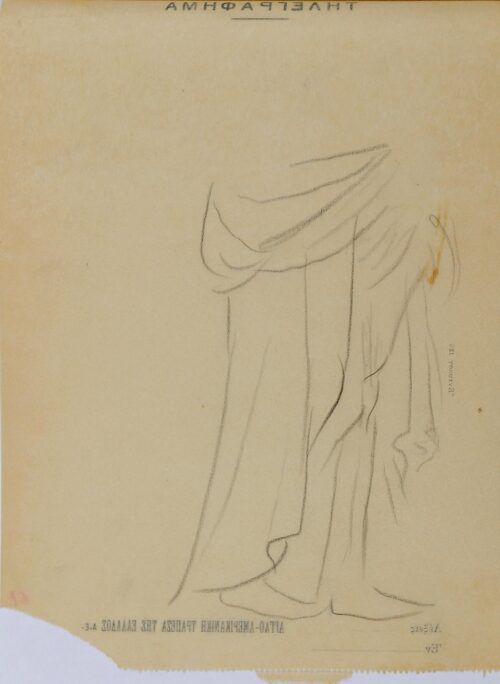

Sleeping Female Figure (Plaster cast from the tomb of Sofia Afentaki in the First Cemetery of Athens), 1878

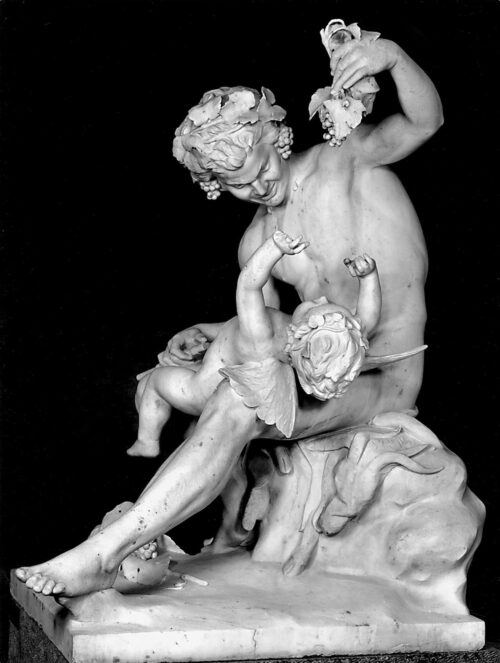

Satyr’s Head, 1878

Fairy Tale of Sleeping Beauty

Athena

Resting Hermes

Satyr and Eros

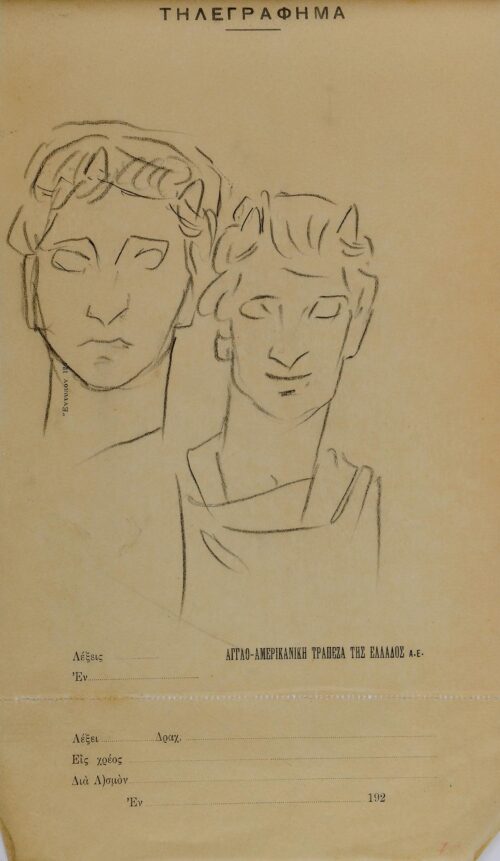

Two Heads of Alexander

Aphrodite

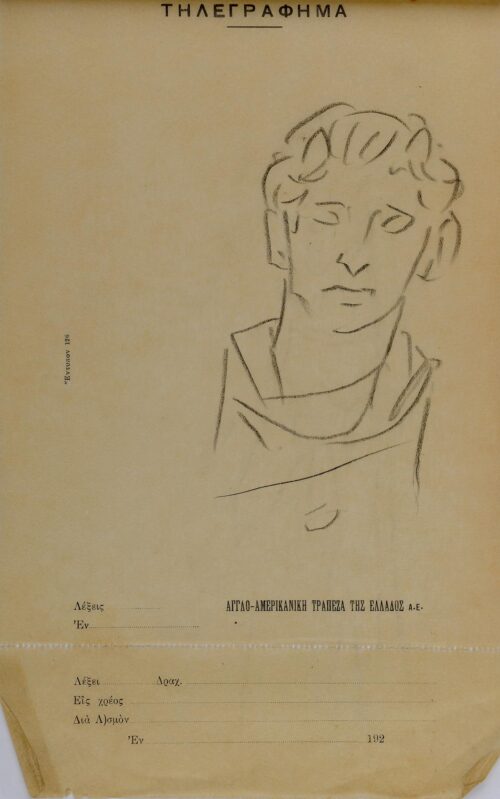

Head of Alexander

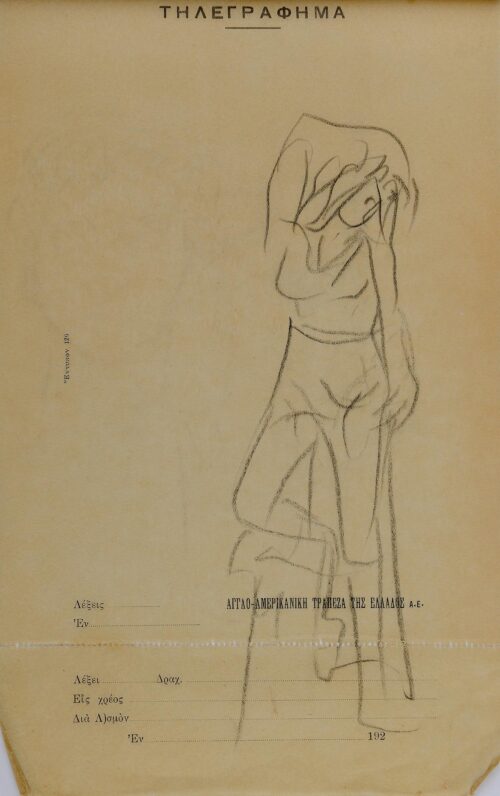

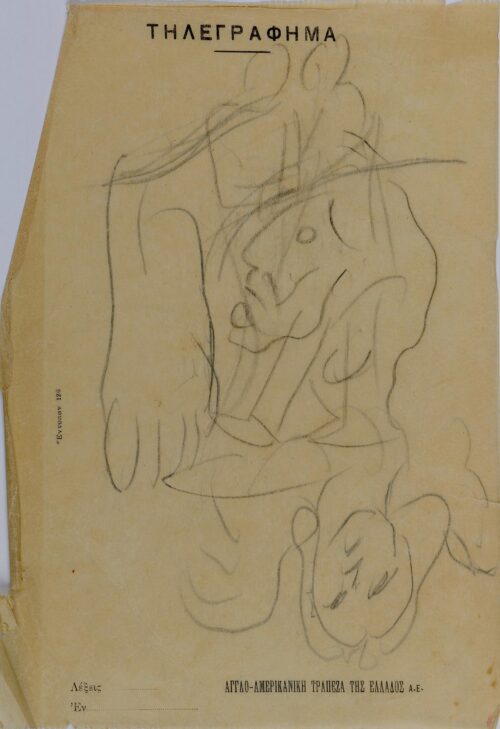

Head of a Man in Profile, Figures, Foot, Head of a Woman

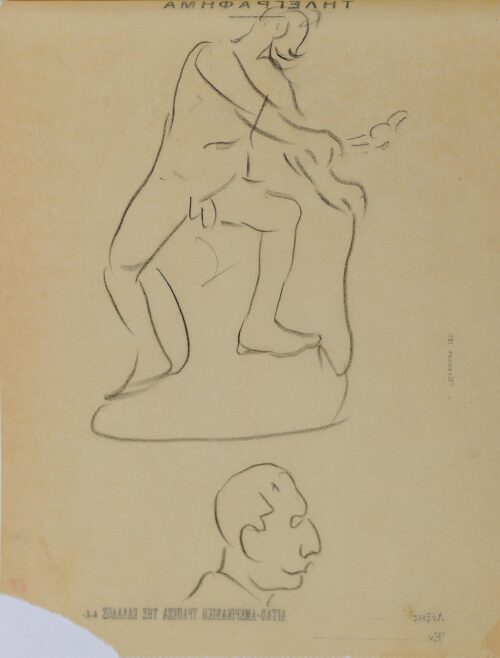

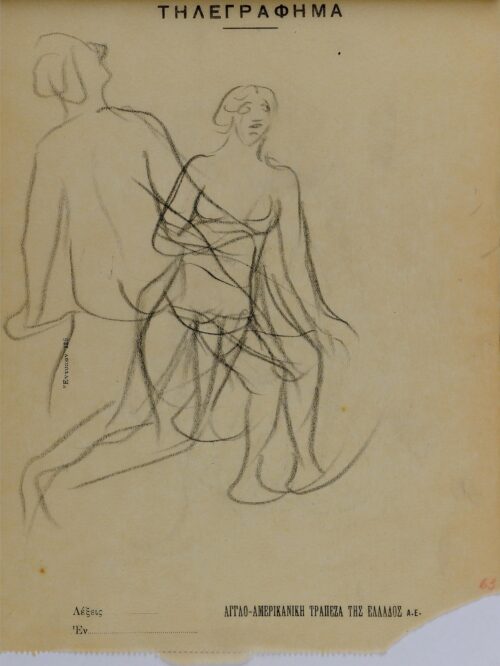

Hermes and Head of a Man in Profile

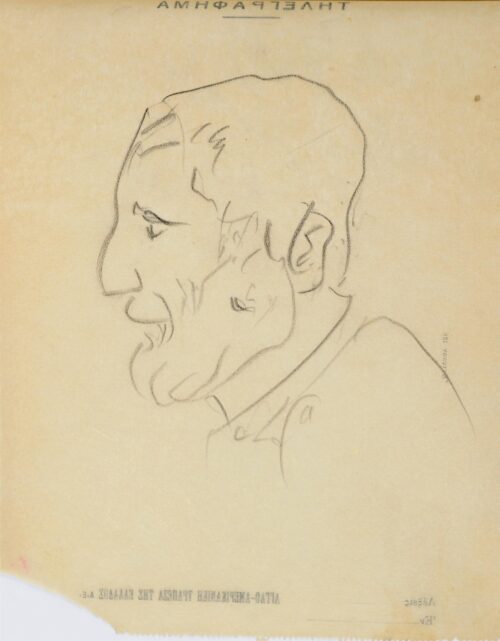

Self-portrait

Satyr and Head of a Man in Profile

Angel

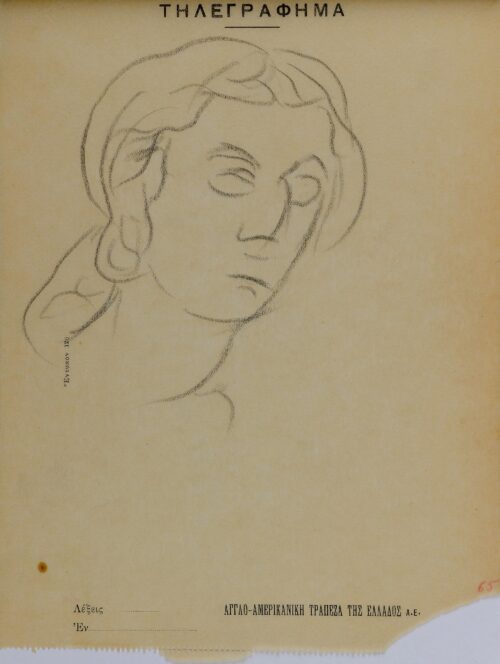

Head of a Woman

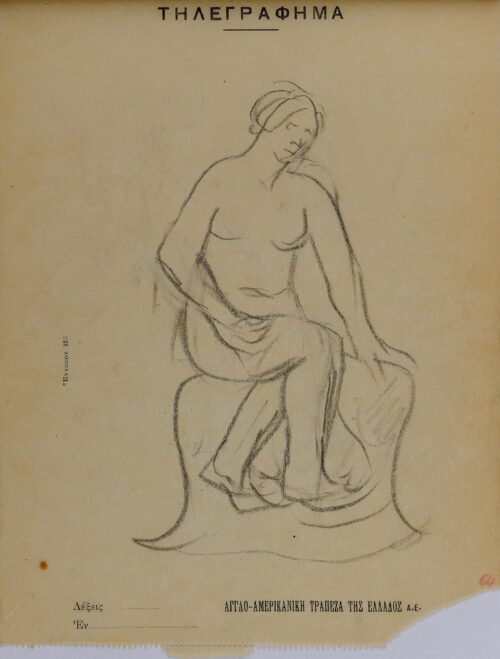

Seated Female Figure (Aphrodite?)

Seated Female Figure (Aphrodite?)

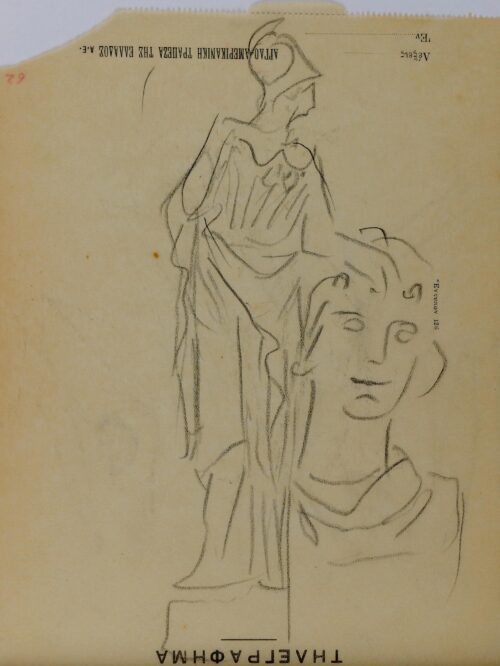

Athena Leaning on a Bust

Angel

Healing of a Blind Man

Fairy Tale of Sleeping Beauty

We use cookies to make our site work properly, to personalize content and ads, to provide social media features and to analyze our traffic. We also share information about how you use our site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners. Read the Cookies Policy.

These cookies are necessary for the website to function and cannot be switched off in our systems. They are usually only set in response to actions made by you which amount to a request for services, such as setting your privacy preferences, logging in or filling in forms. You can set your browser to block or alert you about these cookies, but some parts of the site will not then work. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable information.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

These cookies tell us about how you use the site and they help us to make it better. For example these cookies count the number of visitors to our website and see how visitors move around when they are using it. This helps us to improve the way our site works, for example, by ensuring that users find what they are looking for easily. Our website uses Google Analytics for statistics reporting.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!