Despite the fact the artist was then unknown and the work in poor condition, this painting was purchased by the National Gallery in 1952 for the aesthetic value with which it is so fully imbued. In 1978 Cesare Brandi, in an article he wrote for The Burlington Magazine, attributed this work to Gentile da Fabriano and dated it to around 1418. Then Roberto Longhi and Federico Zeri attributed it to Zanino di Pietro while Keith Christiansen, who agreed with their attribution, dated it to around 1405-1410.

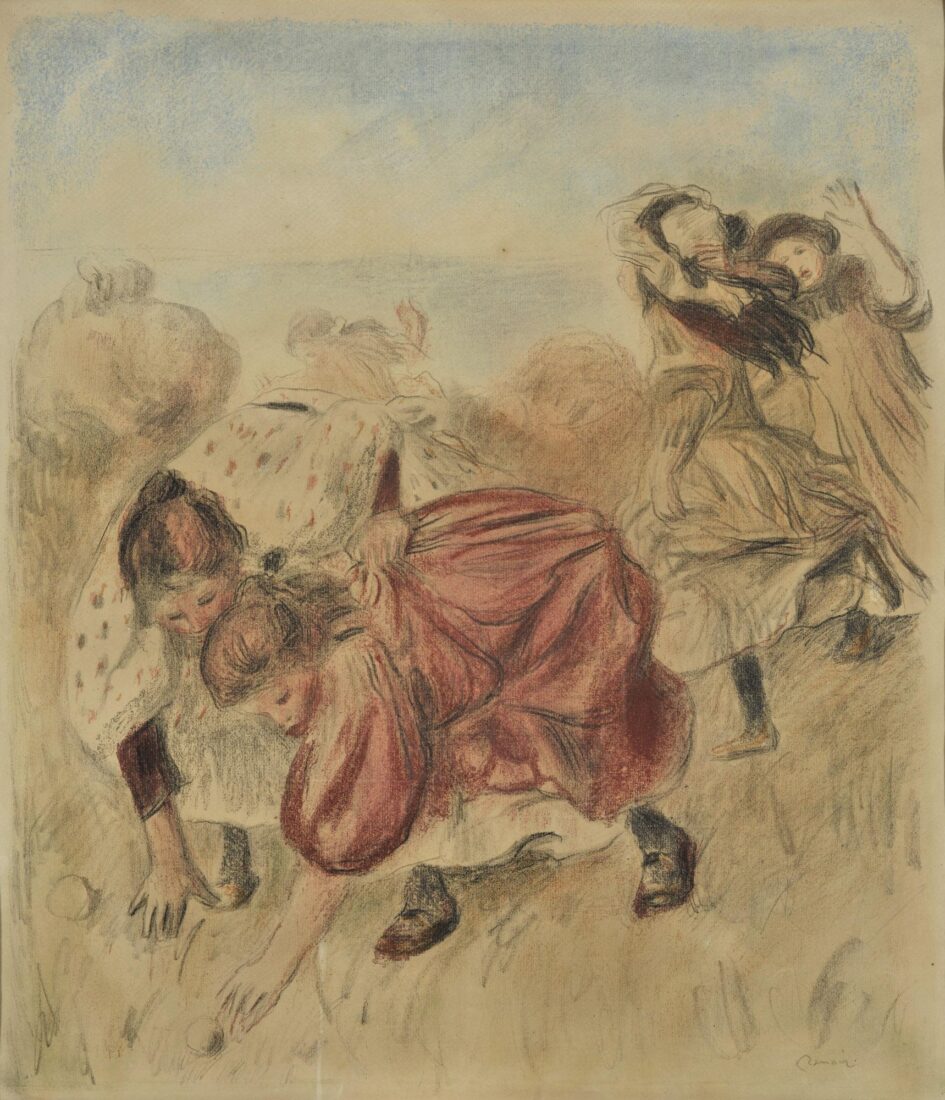

Many of his works, such as the one at the National Gallery, have been attributed to Gentile da Fabriano, which points to the influence these two painters had on each other, while the influence of Michelino da Besozzo, who worked in Venice until 1410, is also obvious. The Virgin Mary with Divine Infant and Angels (a subject often found in the works attributed to this painter) is characterized by the elegance and charm of its late-Gothic style. Following an iconographical method very widespread at the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th century, Madonna dell’Umilta, in which the Virgin Mary is depicted sitting on the ground, the Virgin Mary in this rendition is painted in a flowering field and holding the Divine Infant on her knees. On their artistically rendered halos can be very easily read the inscriptions: Santa Maria Mater Dei for the Virgin Mary, and Jesus Nacarenum rex Judeorum for Christ. On the left their hands are joined in a complex unity with the stem of a flower (today destroyed) which must have been a rose, symbol of both the Virgin Mary and the Divine Passion. Surrounded by five angels, done on a smaller scale, we see the two on the right in an attitude of prayer, a third stretching his arms in praise to the heavens, while the other two, at the bottom of the painting, are gathering flowers.

This painting depicts the army camp of General Karaiskakis at Phaliron during Greek preparations to capture the Acropolis, besieged by the Turks, in April 1827. Greeks and philhellenes are arranged along a section in the foreground, while in the mid-ground on the right, the eye is guided towards the hill from which the leading officers of the army survey the battle field. In the background on the left can be seen the Acropolis. Almost in the centre, a Greek is leaning against an ancient marble in an allusion to the heritage of classical Greece. On the right, a priest is blessing the fighters. The officer in the blue uniform on the left is Bavarian philhellene Krazeisen, to whom the Greeks are grateful. He captured for posterity the figures of the 1821 freedom fighters as we know them today. It is from these drawings that Vryzakis sourced the portraits of the fighters on the hill: Karaiskakis, Makrygiannis, Tzavelas, Notaras, the Scot named Gordon, Englishman Hastings and Karl von Heideck, looking towards the Acropolis through a telescope. Heideck, who had first-hand experience of these events, painted the same subject, and Vryzakis quoted his painting much later, in 1855. The Greek flag sways on the top right. The gold-red and brown colours characteristic of Vryzakis’ work are also pre-eminent in this painting. The description blends tension and suspense with release provided by charming genre interludes.