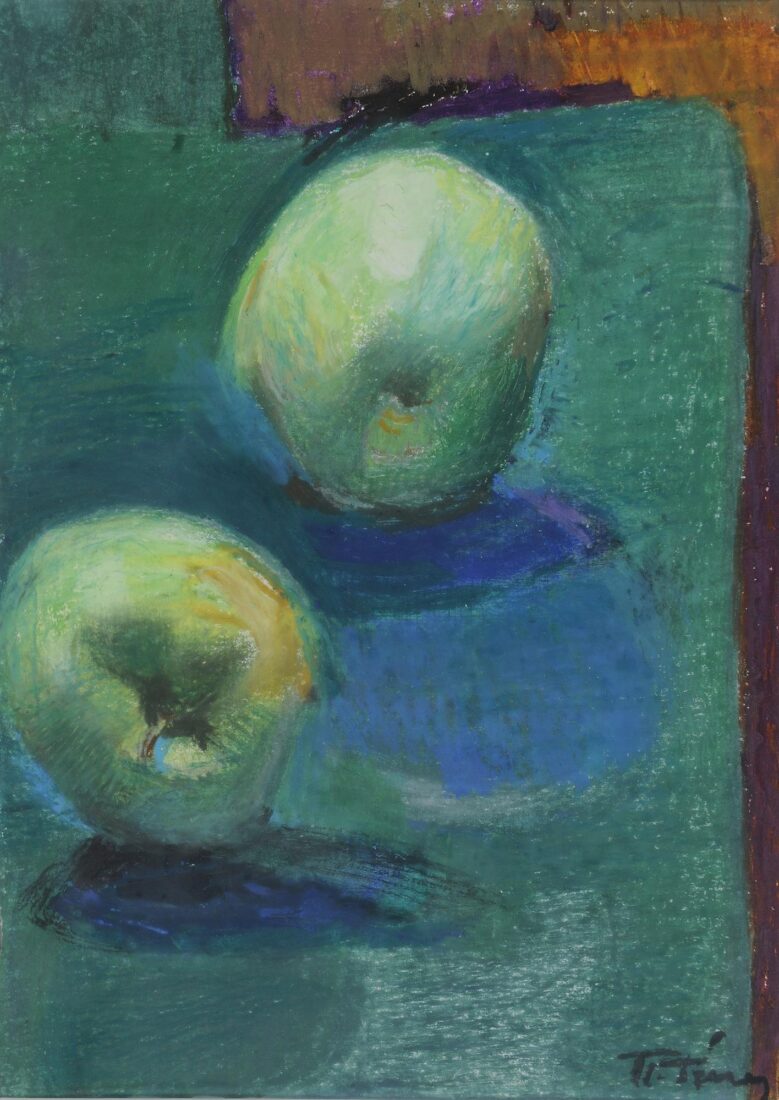

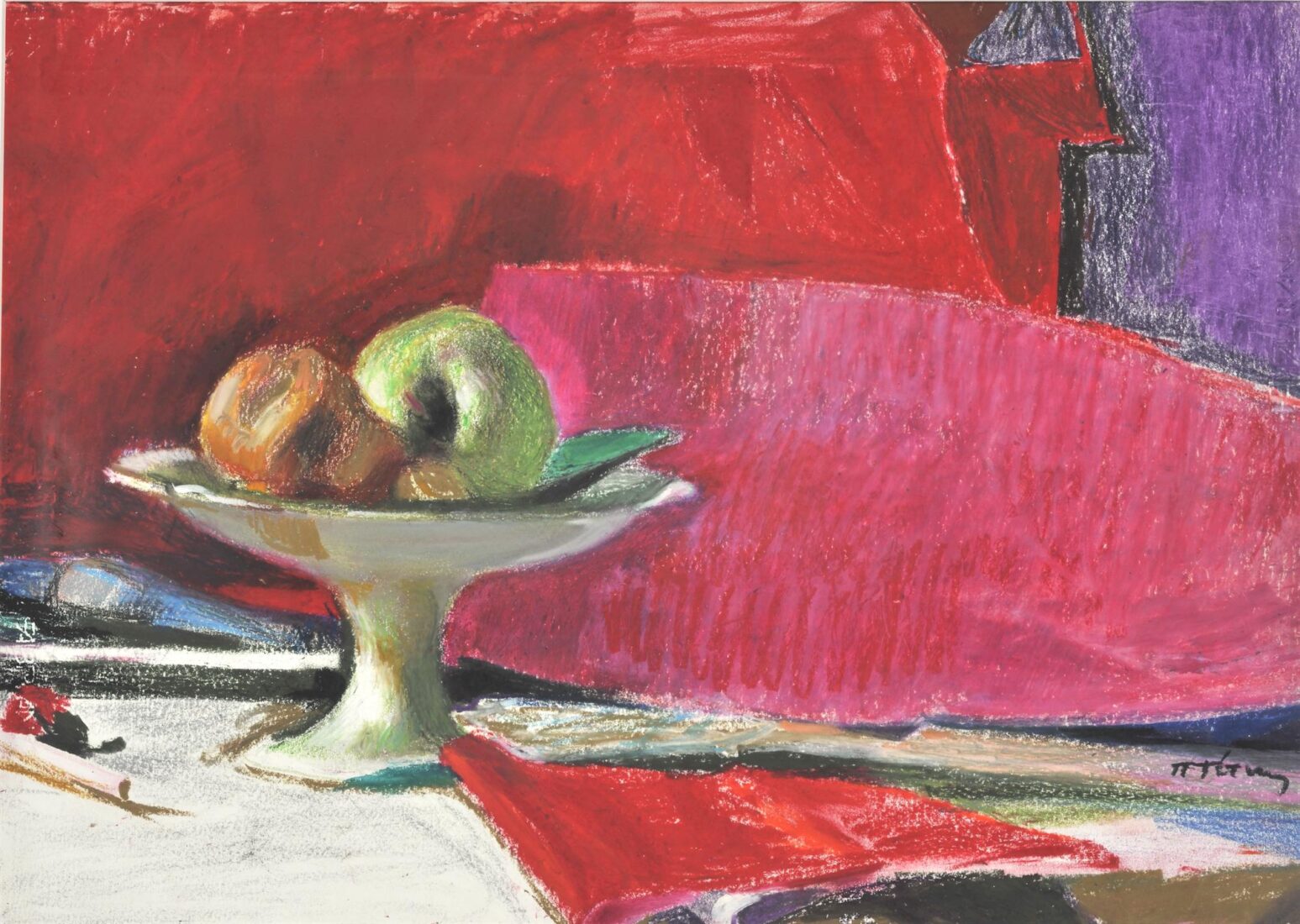

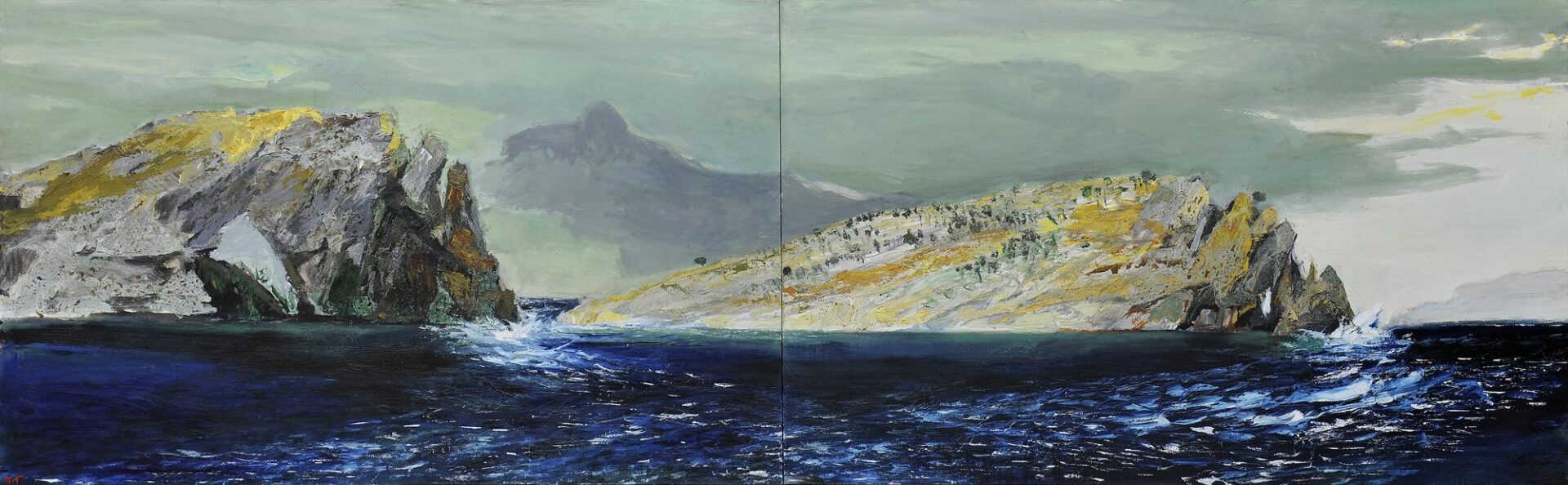

Although Panagiotis Tetsis lived in Paris in the 1950s, when the non-representational currents of abstraction were imposing themselves on art practice throughout Europe and the U.S., he remained faithful to figurative painting. His technique, his free, gestural but always structural brushwork, as well as his palette are testimony to the fact that he was never indifferent to developments in modern art. But he never abandoned his painterly gaze towards imagery that derived from visual stimulus. Landscapes and cityscapes, icons, portraits, and still lifes comprise Tetsis’ typical subject matter. He has a particular affinity for his birthplace, the island of Hydra, the island of Sifnos, where he spends his summer holidays, and the urban Athenian scene. Tetsis’ painting is never descriptive. He pursues the painterly equivalent of reality and renders it in strong colors, establishing him as one of the boldest colorists in contemporary Greek art. This palette is not automatically found in the Greek outdoors, where the strong sunlight tends to wash out just about hue. Tetsis succeeded in giving back to his Greek countryside the force of the color known only in the indigenous landscape painting of the first two decades of the 20th century.

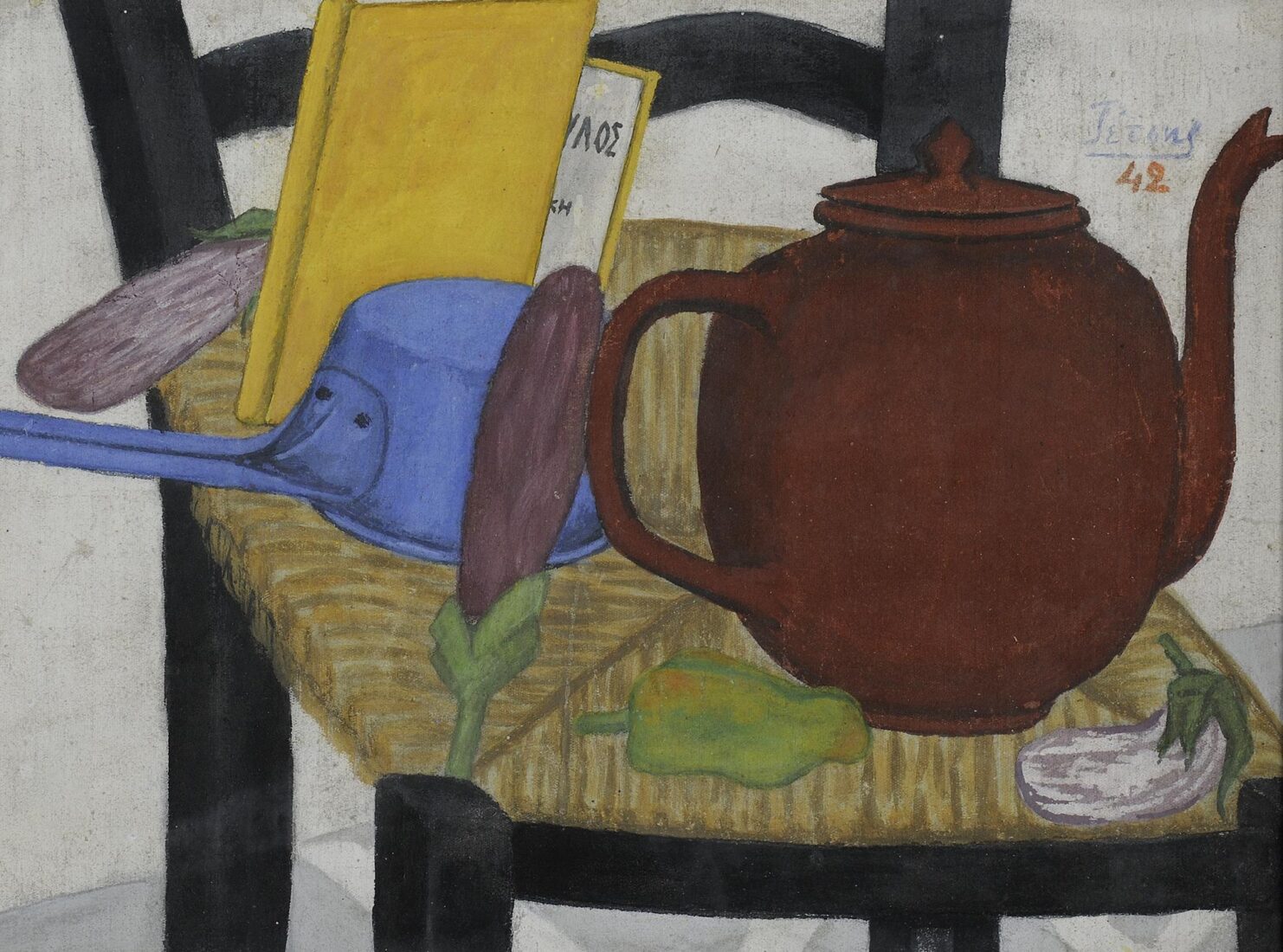

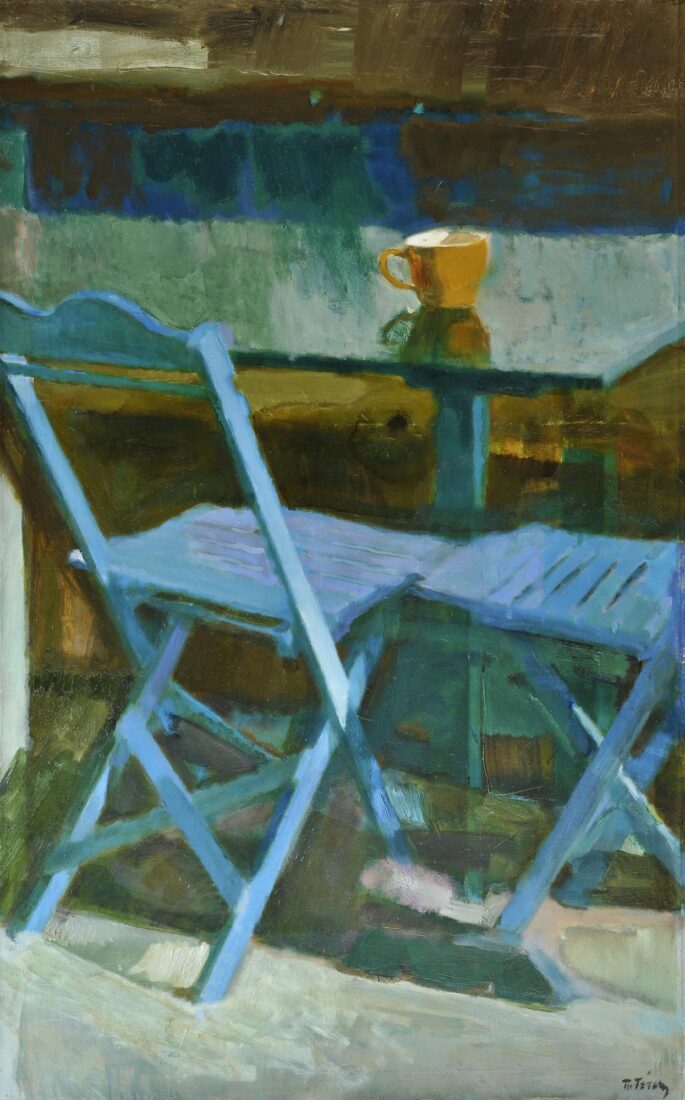

The Blue Chairs II is a typical example of Tetsis’ unrivalled ability to render the intensity of the Greek light, even when limiting his palette to cool colors such as blue and green. The yellow cup, the only warm tone in the painting, dialogues with the complementary blue-violet and enlivens the entire painting surface.