His focus consistently on the human figure, Christos Kapralos fashioned his own personal style through the assimilation of the doctrines of ancient Greek and folk art as well as those of the European avant garde. He made his first works of clay and plaster, realistic but at the same time simplified and pure. When he turned to the use of bronze in 1957 the human body was transformed into Nikes and mythological figures, ancient warriors, couples, mothers and children.

In 1965 Kapralos began using wood, eucalyptus trunks in particular. This gave him the opportunity to create compositions powerfully schematic and strongly non-figurative, obedient to the form imposed on him by the shape of the trunks themselves. Thus, he created a series of works inspired by the events and figures of antiquity, such as “Warrior”, a theme which had occupied him since the Fifties. In contrast, however, to the dramatic intensity which characterized the older compositions in bronze, the “Warrior” made of wood acquires a monumental character and thus is transformed into a symbol of Victory.

This excellent work, acquired in 2002 by the National Gallery, may be considered as one of Volanakis’ most free “impressionistic” achievements. Painted in Munich, it depicts fishermen pulling the nets at sunrise. The boat and the fishermen are shown as silhouettes, as the light is coming from behind, from the background. The sky and the waves are flooded with light, which is rendered in orange and violet tones. The brushwork is free, and the entire work pulsates with life.

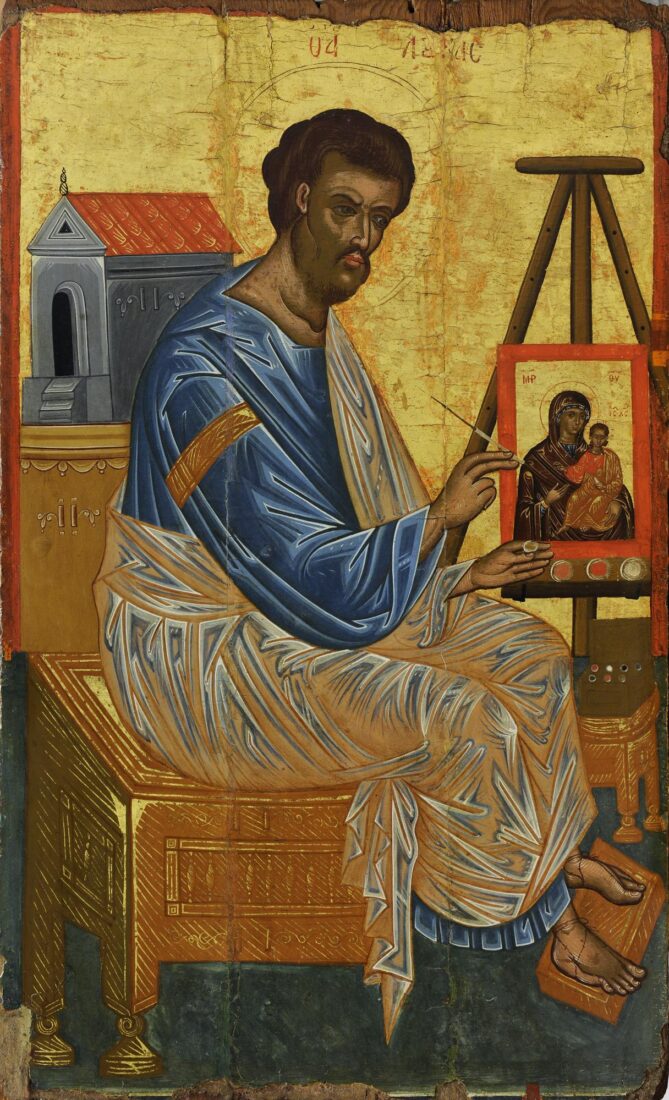

The “Crucifixion” of Christ and the two thieves, the good and the bad, was painted by Andreas Pavias in the latter half of the 15th century, using egg tempera on a wood panel, that is, adhering to the traditional Byzantine iconography process.

The scene is dramatically narrated in many episodes, against a flat golden background. Reminding us that we are dealing with an idealistic rather than a realistic painting, in Byzantine art the golden background denotes the sky; the figures are divine, transcendental, existing outside of time and place, in the infinite space-time. The figures seem lit from within themselves rather than by an external source of light. The scene is arranged in three levels, leading the eye upward, without perspective or depth. On the bottom left is depicted the resurrection of the dead, who can be seen rising from their graves; on the right hand side, the painter has portrayed the soldiers, playing dice for Christ’s crimson robe. In the middle ground, there is the colourful crowd, witnessing the tragic event; the main scene shows the Madonna fainting, supported by the Holy Women and St John, while St Magdalene is throwing her arms around the Holy Cross in lament. A colourful crowd in exotic costumes and hats, horses and a wealth of details complete the scene. On the upper, third section, in which the crosses with the bodies of Christ and the two thieves are portrayed, angels are flying about, in deep lamentation, while others are collecting the Saviour’s sacred blood in chalices. In the background on the left, an angular building structure evokes the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. There is a multitude of always meaningful detail, such as the stork above the Holy Cross, piercing its own breast in order to feed its young ones – a symbol of Christ’s sacrifice in order to save Humanity from the original sin.

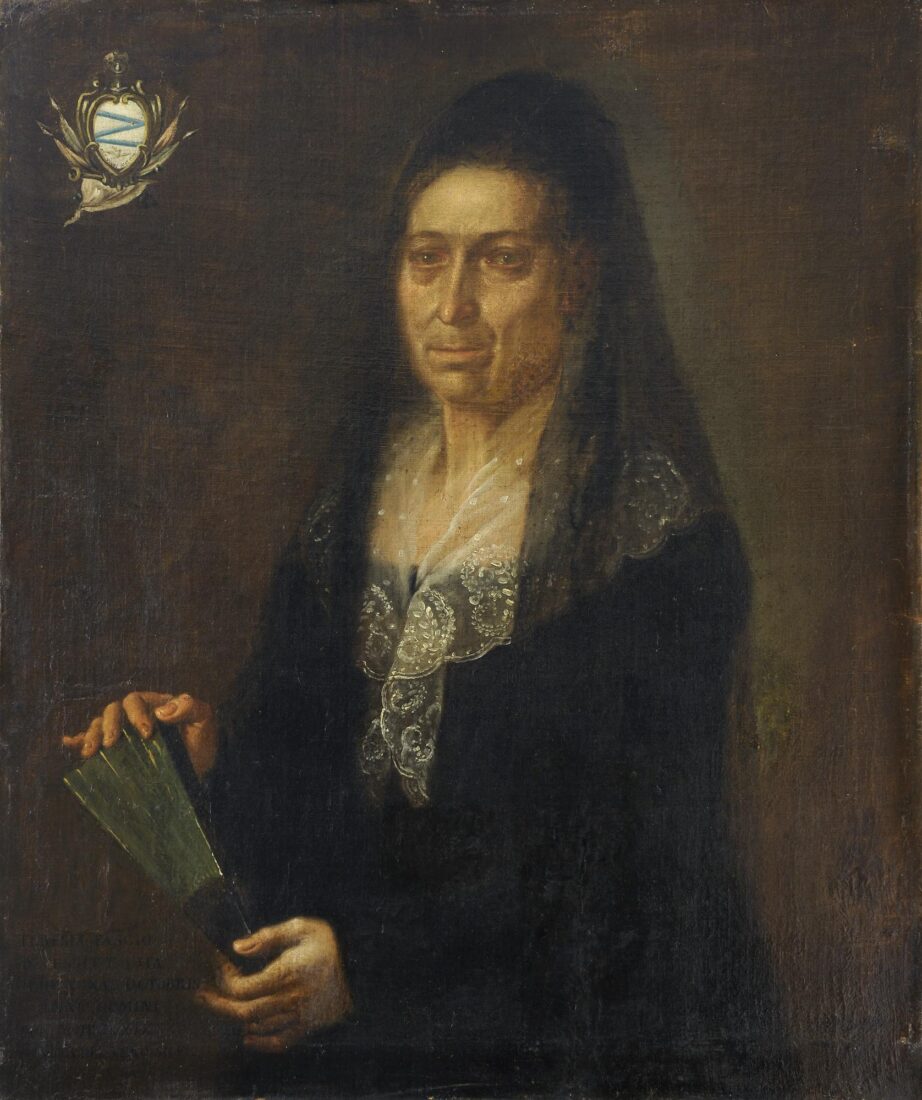

The Cretan artist Nikolaos Kounelakis studied in St Petersburg but lived and worked in Florence, where he was inspired by the great masters of the Renaissance, such as Raffaello, as well as the neoclassicism of his contemporary French artist Ingres, also related to Florence. Both artists, Raffaello and Ingres, sought to capture the ideal figure.

Zoe Kambani was the artist’s fiancee. She is shown putting her engagement ring around her finger, against a solid dark background, her eyes dreamy, as if lost in tender anticipation of love. An opened love letter on the table with the flower vase is the only additional element in the painting. The girl’s comely face, softly modelled, and her plain blue dress underline the classical character of the work.

“Psyche” (ca. 1880-1882) by the Victorian symbolist painter and sculptor George Frederic

Watts (London 1817 – 1904), is a gift of Alexandros K. Ionidis, a great collector of British society, as was his father, Konstantinos Ionidis-Iplixis, and a personal friend of the artist’s.

Psyche was a beautiful mortal maiden, and the goddess Aphrodite was so envious of her beauty that she sent her son Eros to poison with his arrows all men, preventing them from falling in love with her. Yet, Eros himself fell in love with her and, as Psyche being mortal was not permitted to face an immortal, he led her to a palace where he came to visit her only at night, in the dark, without her ever being able to see him. Yet, Psyche, full of curiosity about her obscure husband, one evening while he was sleeping took a lamp and went to see his face. She was astounded by Eros’s beauty and dropped oil from the lamp on him and woke him up. Angered by her curiosity, he left. In regret, she looked for him everywhere and, after many trials, with the help of Zeus, who made her immortal, reunited with Eros for ever.

In Watt’s work (a different version of the work in the Tate Gallery, inv. no. 1585), the only hints for the story of Psyche are the feather on her foot, the lamp fallen on the ground, and the bed in the background. On the contrary, the idealized “impersonal” slim and tall nude female figure personifies pure divine eros.