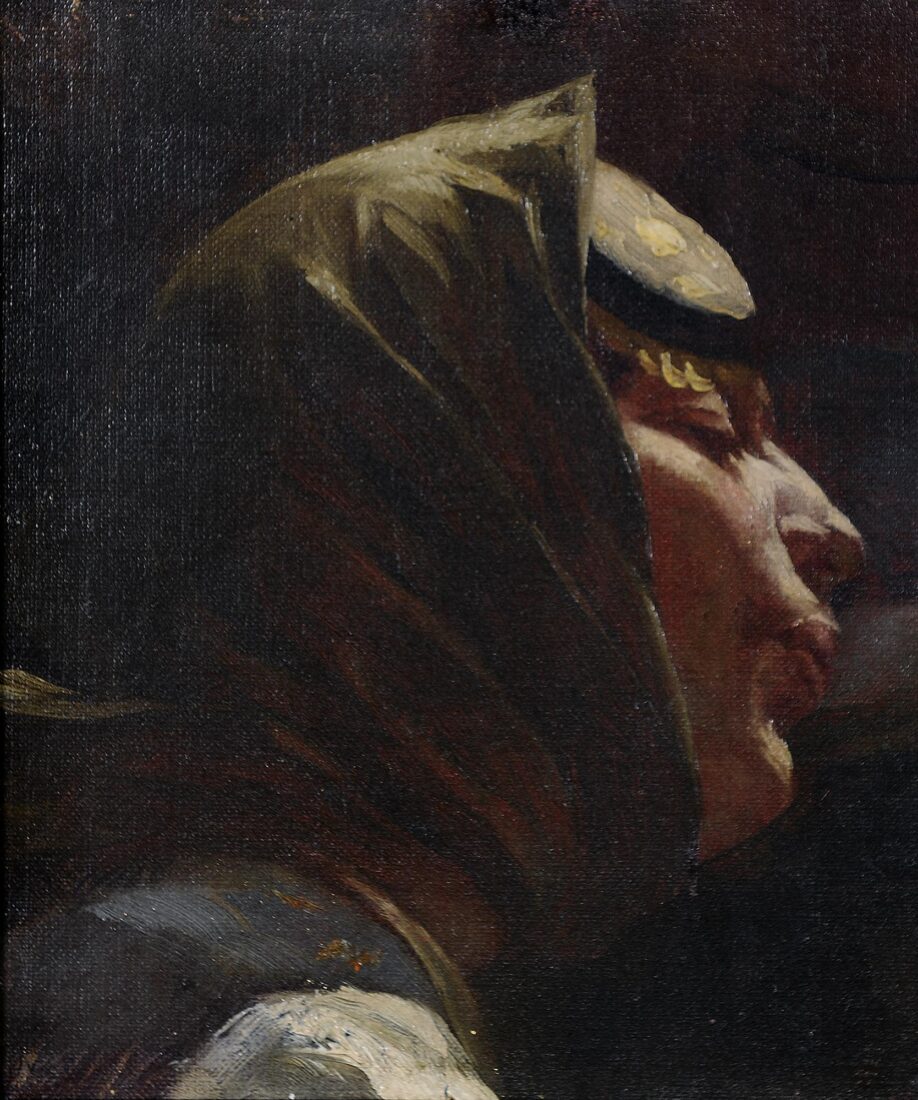

Iakovidis is the last great exponent of the Munich School. Although he distinguished himself in many genres (genre painting, portraiture, still life), he was mainly known and loved by the people as a painter of childhood. Most of his works on this theme were painted in Munich, where he lived from 1877 to 1900, when he was invited to return to Greece and become the director of the National Gallery, which had only recently been established. Iakovidis inimitably captured the relation of the elderly, grandfathers and mothers, with their grandchildren.

This work features a dark-clad goodly grandmother, holding a cute blonde little girl in her lap; the child is wearing a white flowery apron and red socks. The bronze fruit plate has captured her attention — a great opportunity for the artist to create a wonderful still life. The scene unfolds against a white wall, contrasting sharply to the dark-coloured main subject. Everything has been painted with an extraordinary knowledge of drawing, colour, light as well as profound insight into the psychology of the relation between the two ages.

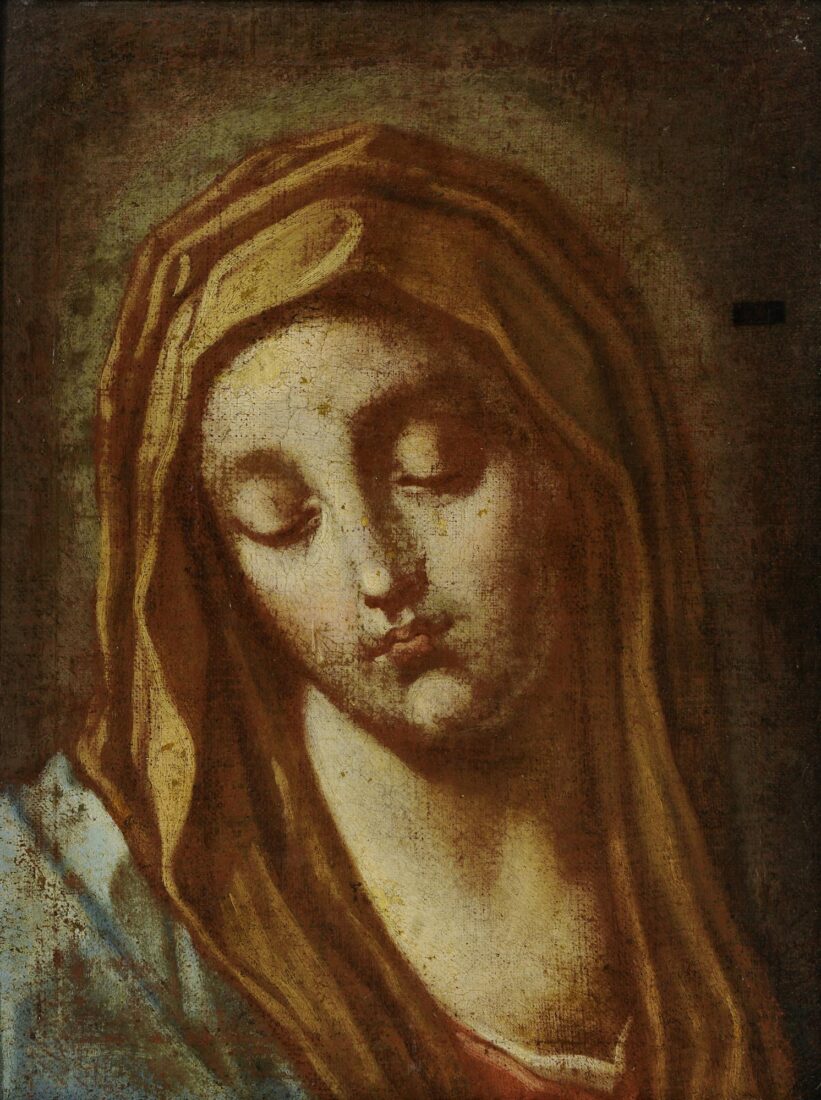

When this work was made part of the collection at the National Gallery, it was at first attributed to Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652) who settled in Naples where he became acquainted with Caravaggio and fell under his influence. Professor Gerhard Ewald, however, attributed the work, in his book Johann Carl Loth (1632-1698), Amsterdam 1965, to the German painter Johann Carl Loth.

In the work at the National Gallery one sees, in all likelihood, a depiction of Plutarch’s version of how Archimedes died. This occurred during the conquest of the Syracusans by the Roman legions under Marcellus. “As fate would have it he was alone, intent on working out a problem by means of a diagram. And as both his mind and his eyes were absorbed with these speculations, he remained completely unaware of the Roman incursion, not even realizing the city had been taken. Suddenly, he found himself face to face with a soldier who commanded him to follow him to Marcellus. But Archimedes refused to budge until he had solved the problem to his satisfaction and demonstrated it. This infuriated the soldier who drew his sword and ran him through…” (translation of the relevant section on Marcellus of the Greek edition of “Plutarch’s Lives”, edit. Philologiki, vol. II, Athens, n.d., p. 212). In the painting, the soldier, holding his sword in one hand, has lifted it with a violent movement and is holding Archimedes by the throat; he appears quite unfazed, with an absorbed look and making an emphatic gesture which shows his determination to not go with him until he has solved the problem he is involved with.

The composition is faithful to all the elements characteristic of Loth’s works. The soldier and Archimedes create, with their bodies, the sphere and the account books, a compact group that occupies nearly the entire surface of the painting. The soldier, tall and well-built, is in almost complete shadow, standing behind Archimedes’ uplifted arm while the light falling on the primary plane in practically the center of the composition, creates contrasts between the light and dark planes, revealing the elderly body of Archimedes, still strong despite his great age, as well as his strong-willed personality. The dark brown colors in combination with the intense lighting serve to stress the dramatic character of the scene.

A poet, musician and painter who studied in Italy, Georgios Avlichos, the Cephalonian artist who created this masterpiece, was completely removed from the academic tradition of his times. There is something poetic and eerie about the atmosphere in his works; an almost metaphysical aspect, heralding de Chirico and Balthus, a contemporary painter. Another characteristic quality that set Avlichos apart from other artists of his period is that he steered clear of the brown asphalt employed by academic painters, painting instead in clear and bright colours.

What is it that the young Roubina (for her name is known to us), the daughter of Ioannis Gerasimos Kavalieratos, is gazing at through the open window of her country house at Vlachata, Sami? She is gazing at the blue sky in reverie, and the little white dog she has in her arms seems equally absorbed by the same vision, invisible to us. Her ethereal white dress, painted in light lilac and ochre hues, contrasts with her black fan and loose, crow-black hair. A sea breeze, the scented zephyr of the Ionian Sea, blows on the girl’s hair, scattering the petals of the red rose in it. Can it be that this scattering of the rose petals is a symbolic allusion to the fleeting youth, torn apart like a rose by time?

“St Peter” belongs to a series of portraits of Christ and the Twelve Apostles which was first produced by El Greco, called “apostolados.” Such works frequently decorated the treasury in Catholic churches, where the sacred utensils of the church were kept.

“St Peter” is an austere, realistic figure, meditatively gazing beyond the viewer. He is holding in his hand the keys he was entrusted with by Christ. The blue robe and orange himation have been rendered in broad brush strokes; white lights run across the foldings like lightning, evoking the lights and golden trimmings in Byzantine art.

![Belle Epoque Lady [Portrait of Sophia Laskaridou]](https://www.nationalgallery.gr/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/79144_2000_2000-559x1100.jpg)