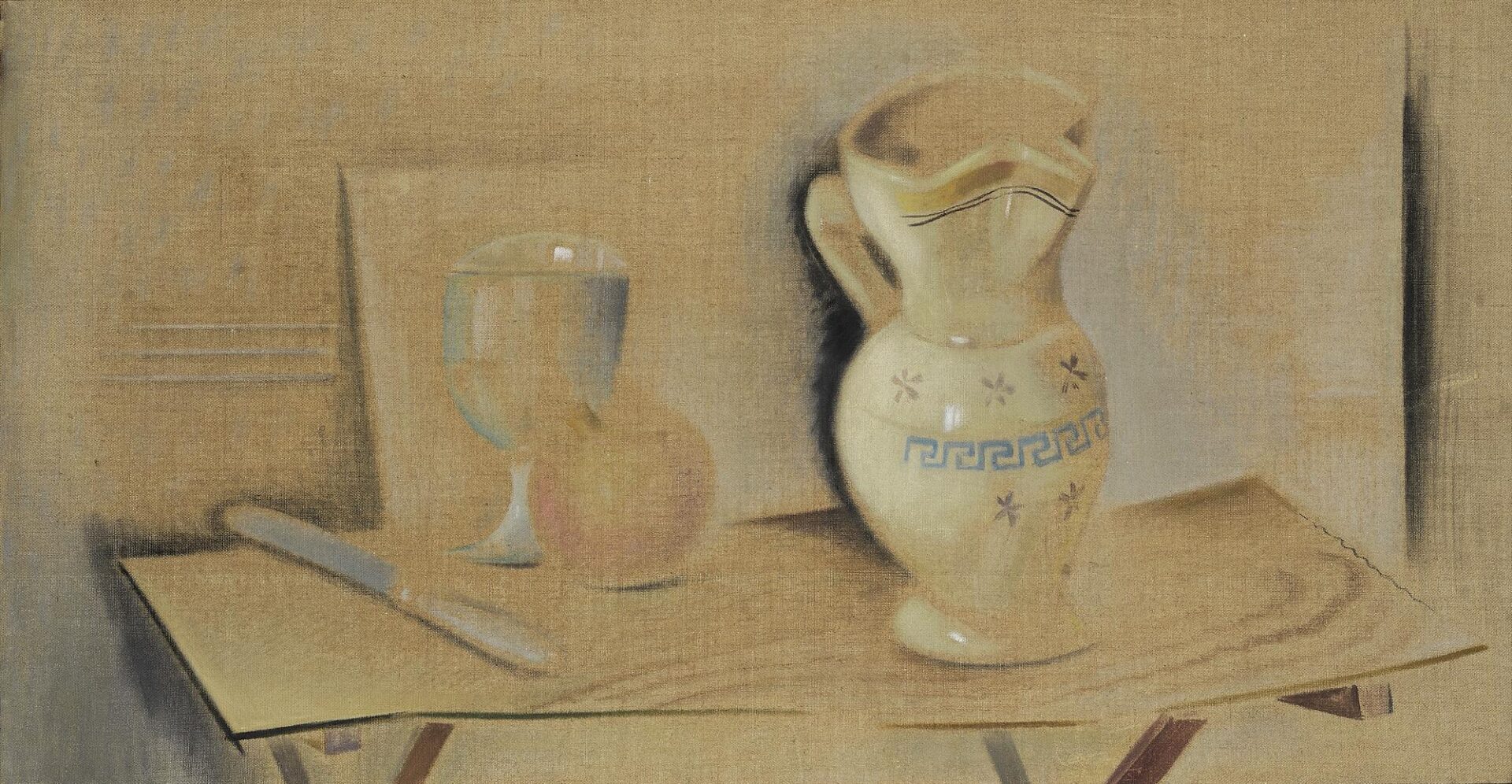

The “Harbour of Kalamata” introduces us to the poetic and lyrical atmosphere of Parthenis’ painting. What can we see in this painting? A quay with benches and a red lighthouse at the end. A ship with open sails painted yellow. A violet mountain in the distance. And a sky with faint clouds, in which we find once again, in softer tones, the colours of the sea and the mountain. The entire work is lightly painted, allowing the spaces between the colour areas to breathe. The harmony of colours is based on the interplay of blue-purple and yellow-orange. In other words, a conversation between cool-warm and complementary colours. The composition is based on the large horizontal line of the sea, the vertical lighthouse and the diagonal quay. The ship with open sails balances the weight of the elements that would otherwise be heavier to the right.

Although the quay has been drawn in perspective, in fact the painting has no depth. This is because there is no atmospheric perspective, as it was called by the old painters. In other words, the more distant objects — the quay further in the distance, the mountains — have not been painted using fainter tones in order to suggest distance. In modern painting, the artist seeks to keep the image within the canvas plane, avoiding the illusion of three-dimensionality.

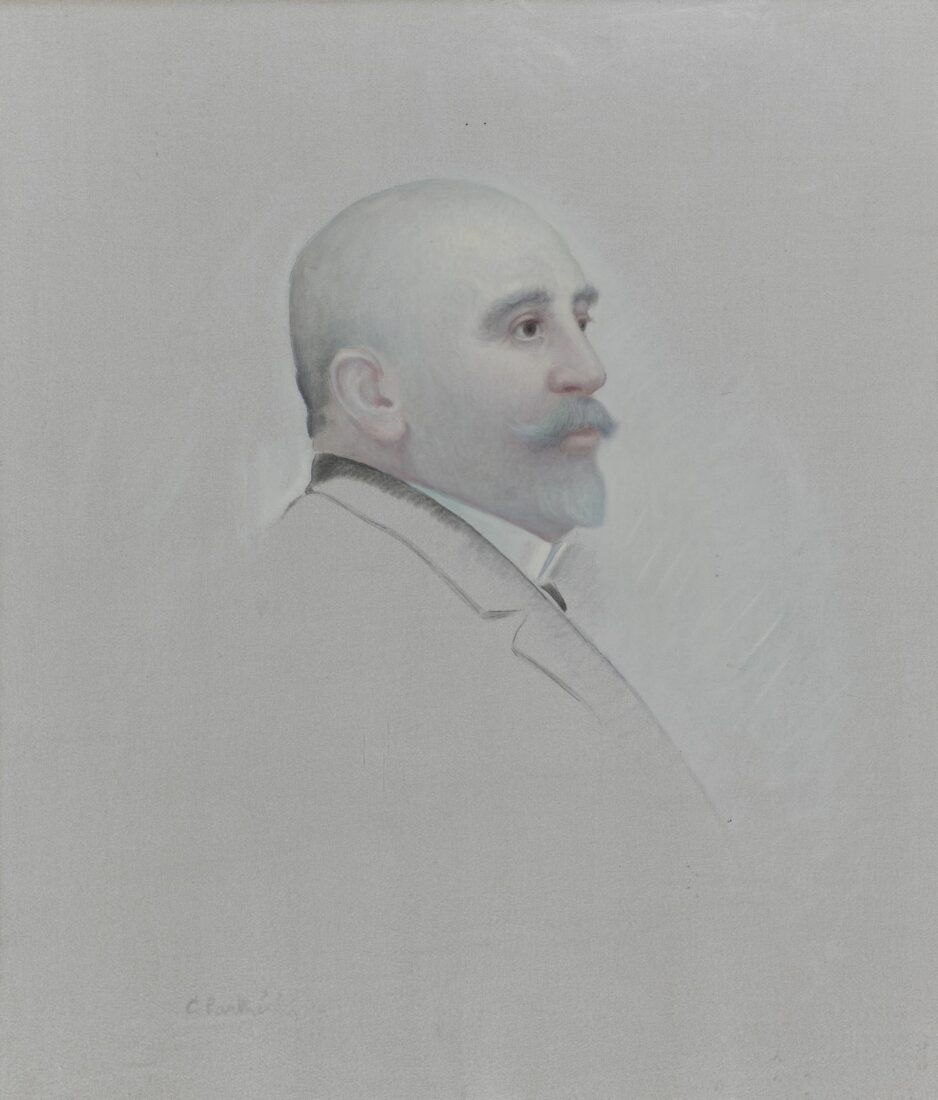

Ioannis Vaptistis Kalosgouros belongs among the Ionian island artists who revived the art of sculpture in the Ionian, creating the first works of modern Greek sculpture.

The bust of the illustrious Hellenist and Philhellene Frederick North, Count of Guilford (1776-1827), who in 1824 founded the Ionian Academy on Corfu and with whose financial assistance a number of later to be illustrious Greeks studied abroad, is almost a faithful copy of the bust Pavlos Prossalentis had made in 1827. The English Philhellene is depicted wearing the specially designed ancient-style uniform of the Lord of the Ionian Academy. His mature age is expressed by the wrinkled cheeks and the stringy but at the same time rather loose neck while his gaze is fixed, in keeping with the neoclassicist model. The thin hair on his head is framed in relief by a decorative band with an owl in the center, the symbol of education. The imposing rendering of the figure expresses self-confidence and satisfaction and stresses the count’s dynamic personality.

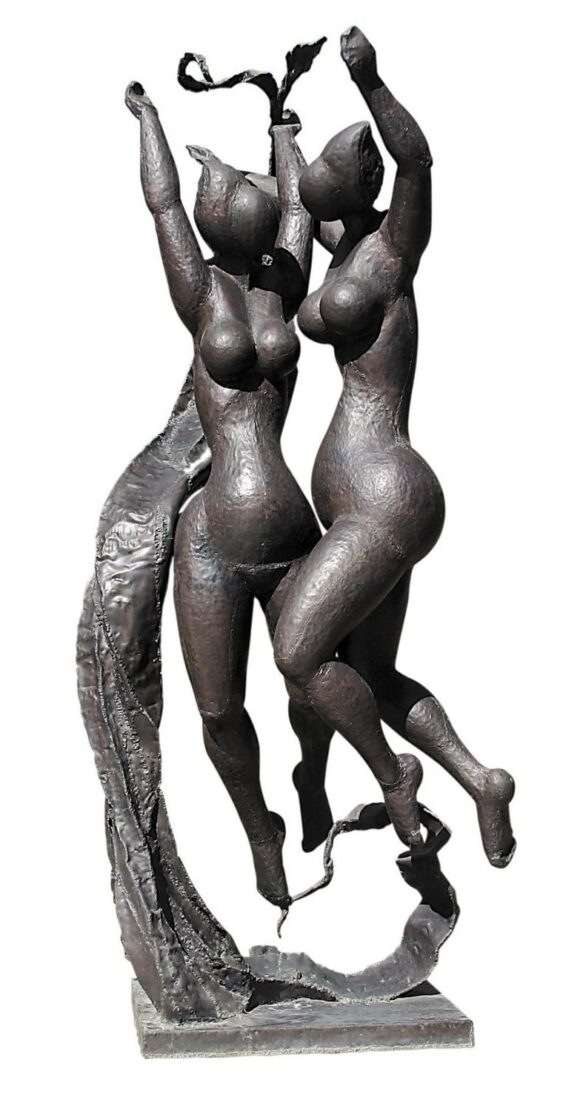

A sculptor who centered his attention on the human figure, faithful to representation but with a strong tendency toward the schematic and the abstract, Memos Makris studied at the Athens School of Fine Arts, and then attended lessons in the studios of Jean-Paul Laurens and Marcel Gimond in Paris, where he lived for five years, settling in Hungary in 1950. Busts, female figures, nudes, and monuments designed for public spaces, made up the core of his work, which drew elements from both archaic art and his French teachers and, occasionally, abstract and expressionist models.

In 1965 he began working on a number of naked figures. These figures are rendered very schematically, with oval heads and sometimes with the characteristics of their physiognomy simplified, and other times without any characteristics at all, with the bodies all worked the same way, with rounded volumes and elongated forms. The “Spring Dance” follows along these lines, but the abstract rendering is even greater, while the two figures hover in the air in a laudatory dance in honor of spring, recalling scenes from the three Graces in compositions of European art.

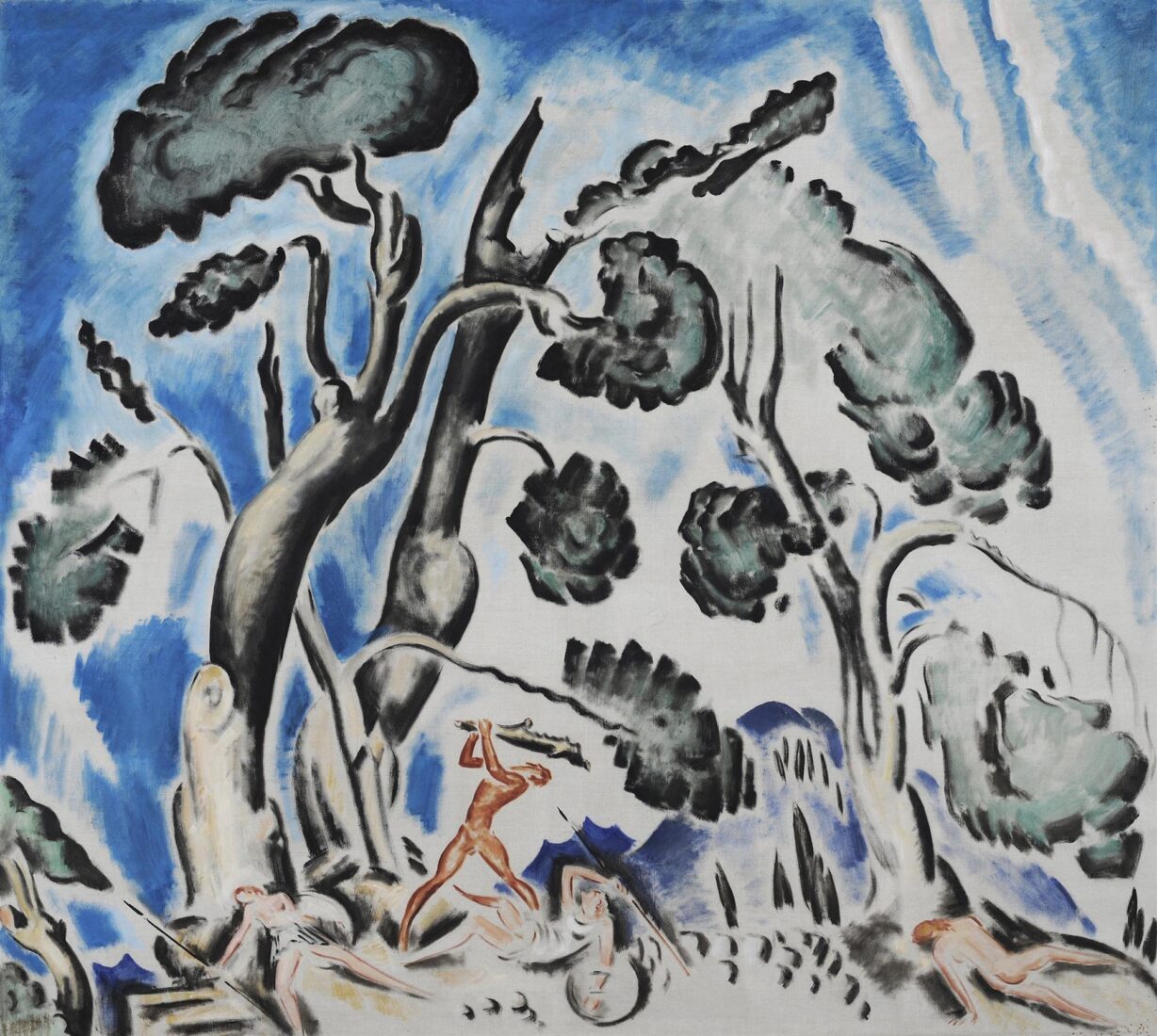

We have already met Konstantinos Parthenis in his first creative period, that of outdoor painting. After 1920, he turned towards anthropocentric, symbolist and allegorical subjects. With its powerful stylisation and light tonal palette, which makes his nimble, tall and thin figures seem like dreamlike projections on the canvas screen, Parthenis’ mature style had fully developed by this period. His works painted in this style seem like poetic reverie.

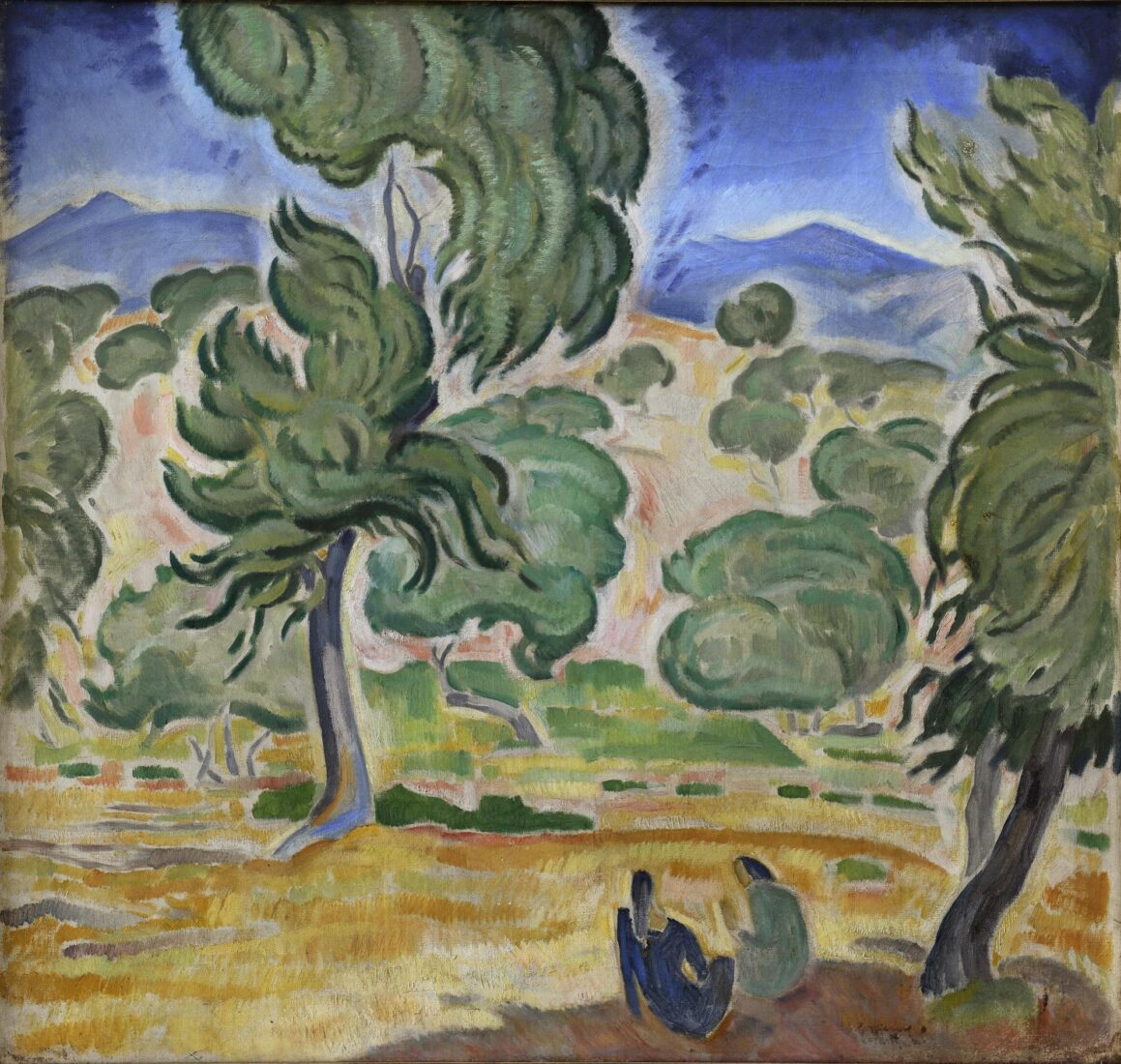

In the Thirties, certainly under conscious or unconscious influence by the predilections of that generation, Parthenis’ style changed. The curvilinear forms noted earlier now gave their place to a linear, angular writing, which often seemed to be supported by drawing instruments, such as the ruler and compass. Another notable change, probably related to Kontoglou’s return to the values of Byzantine art, was that the fresh, jubilant spring colours of the previous period were now replaced by the Byzantine palette and its earthy colours – brown, grey, dark blue. A common element with the previous period is the light hand, almost not human, which allows the canvas to show through and transforms the figures into dream-like fantasies projected on the painted surface.

Let us now “read” this monumental painting, an apotheosis, according to its title, of the great Greek revolutionary hero, Athanassios Diakos, who died a martyr’s death, near the Alamana Bridge on April 24, 1821.

The following lines are attributed to him by folk tradition:

Oh, that Death chose to take me now,

when the twigs are in full blossom and the soil is covered with fresh grass.

The artist seems to have had these lines in mind while making this monumental work, one of the crowning masterpieces of modern Greek art. He identified the hero’s resurrection and ascension with Christ’s Resurrection, both events occurring in the spring, around the month of April. On the left, a haloed figure, an Angel or one of the Myrrhophores, is startled upon discovering the empty tomb of the resurrected hero. In the middle, another angel, wearing a helmet and carrying a spear and shield, reminding us of a Christian goddess Athena, witnesses the miracle. Athanassios Diakos, in a classical chiton, rises in heaven, where he is received by angel musicians, similar to those in Greco’s paintings, while others are bringing laurel wreaths in order to crown him. A girl, as if out of Botticelli’s “Spring”, is sprinkling the hero with flowers from her lap. Incense is burning in a tall classical incense burner. The painting elevates the Greek Revolution into the sphere of the ideal world. The idealisation of history is also achieved through the symbols and the iconographical spirituality of the work.

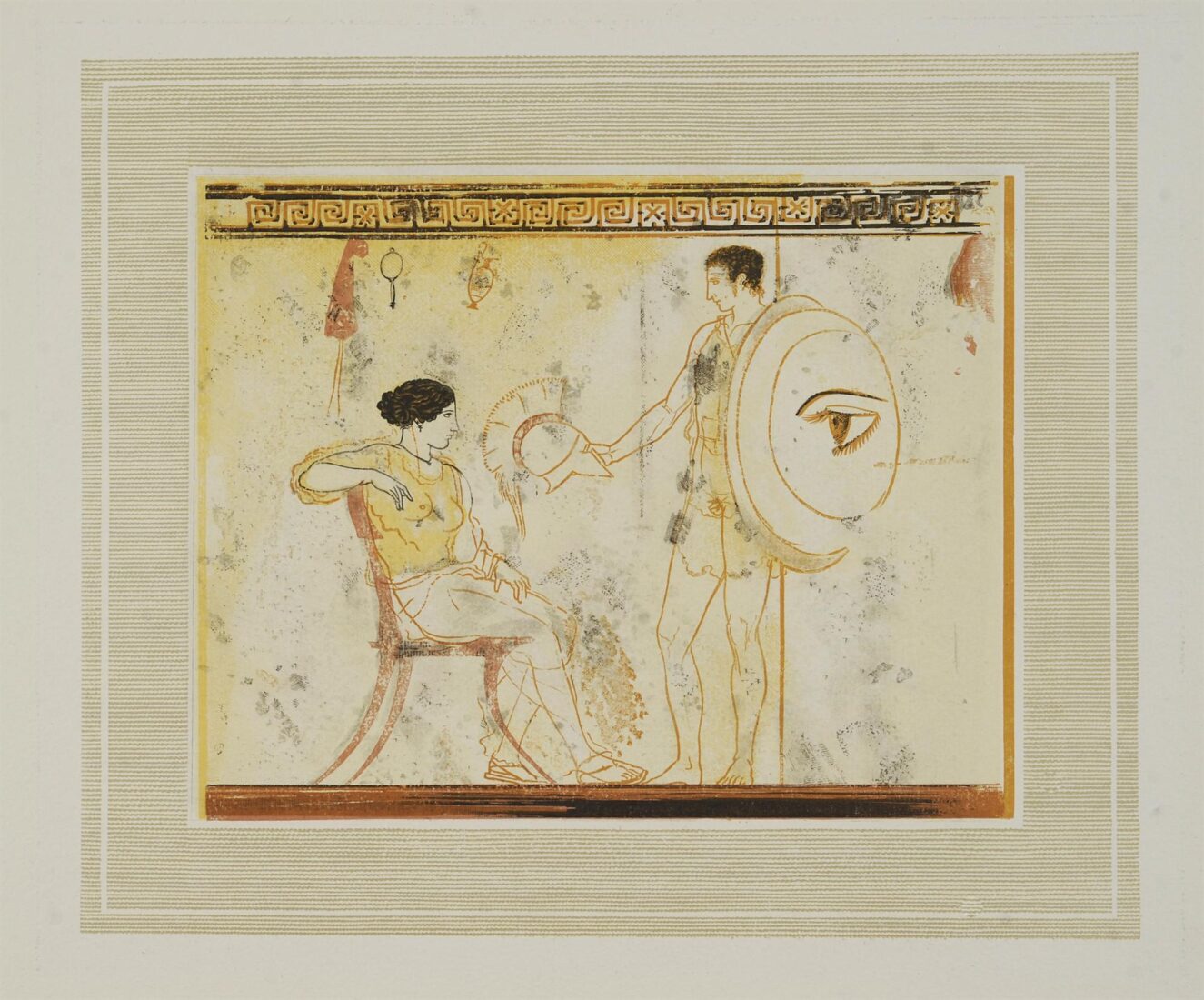

In “The Apotheosis of Athanassios Diakos”, various influences, both iconographic and stylistic ones, join and blend: The drawing echoes classical pottery. The hero’s resurrection and ascension comes from the related Byzantine iconography. Flora, the personification of Spring in Botticelli’s work of the same title, is the iconographical source of the girl on the right.

Greco’s tall and slender mannerist figures, as well as his bipartite arrangement of his works in an earthly and heavenly section have inspired the morphology and composition of the Apotheosis. The geometric shapes and broken outlines, where space and form mingle with each other, reveal the Cubist* influence on Parthenis. Moreover, his cerebral, anti-naturalistic colours also originated in Cubism. This influence was reinforced by the shift towards the Byzantine tradition by the “Generation of the Thirties”.