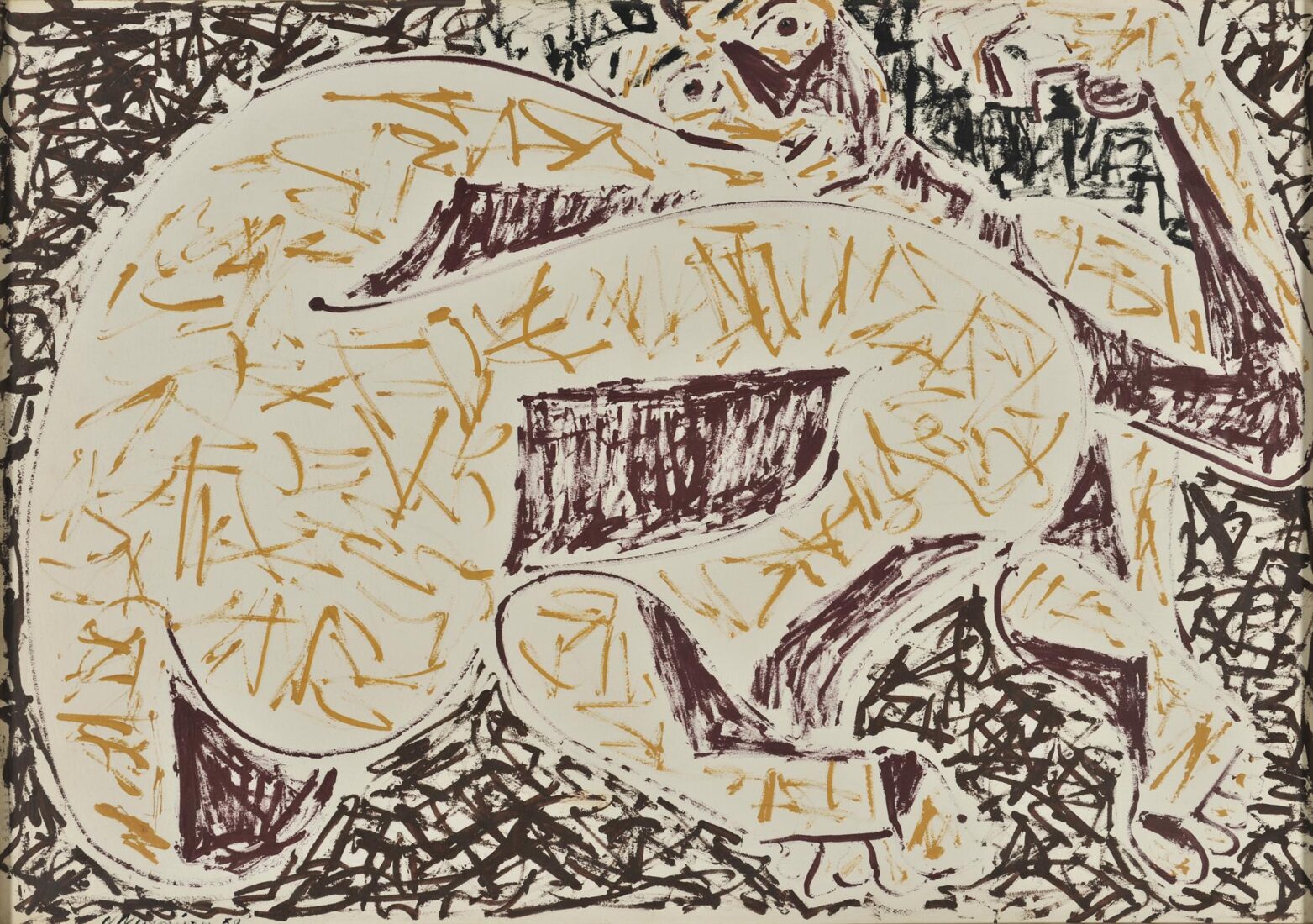

Time, deterioration and their antidote, memory, are the focus of Sotiris Sorogas’ oeuvre. With reverence and affection he paints parts of old machines that, after having served man, have been abandoned to the mercy of rust and time. Sorogas has retrieved these now useless carcasses from oblivion and silence by painting them with the flawless, sensitive style that characterizes his technique. The picture of the iron relic, painted in the brownish shades of rust, takes on another, almost metaphysical dimension, suspended as it is on the white canvas. The texture of the medium, the space, the voids, and the feeling of silence and arrested time play major roles in Sotiris Sorogas’ individualistic painterly idiom.

Pantelis Chandris studied graphic arts and painting, but his enterprise has a clear conceptual direction that is expressed primarily through constructions and manipulations of the space. These constructions and spatial manipulations draw either on nature or on human needs and pursuits connected to the conscious and unconscious. They are fashioned with the help of a visual reality that nonetheless has a symbolic character.

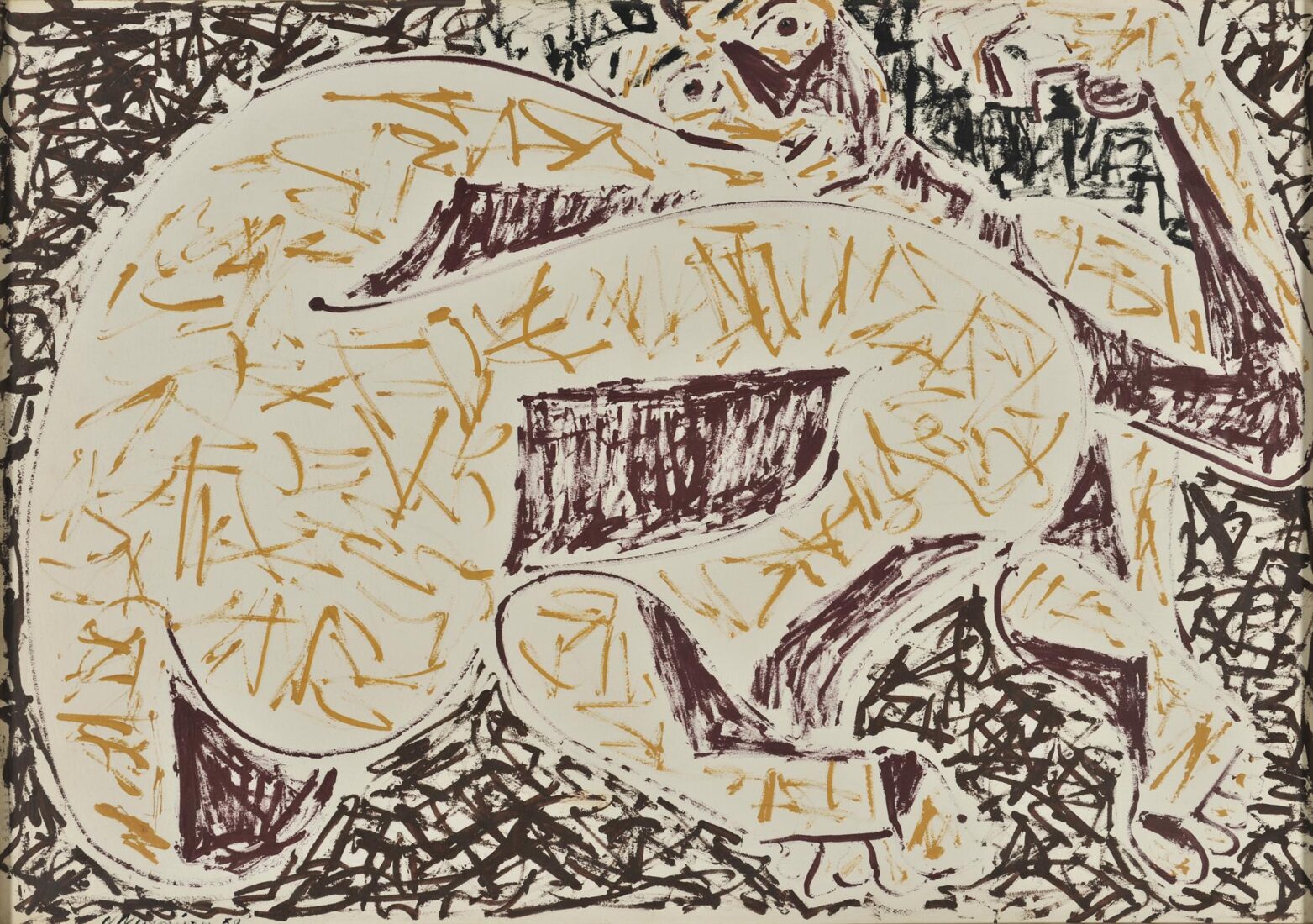

The male figure in an overcoat appeared for the first time in the trilogy “Conversations with a Wintry Figure”. It then became the basic figure in a series of pieces bearing the general title “States of Being”. “Hunter” comes from this series.

According to Chandris, the hunter-predator is identified with the Ego, the dog, the essential hunter, with the Superego, and the bird with the Id. Thus he gives form to a psychoanalytical structure as Freud analyzed it. The symbolic combination of these three figures enables Chandris to express a variety of conscious and unconscious states of being while allowing the viewer to interpret the work from a personal perspective.

Frosso Michalea chose to express herself through abstraction since, even during her brief stint doing figurative depictions of the human figure, she used strong schematization. She made use of different materials, such as marble, wood, and stone in order to realize series of works such as “Dialogues”, “Landmarks” and “Transformations”. During the Eighties she turned to metal, giving form in 1985 to the series “Movement in Space and Time”, using steel as her material and at the same time introducing color into her works. Furthermore, while her forms until then had been closed and the compositions static, with this series she introduced the feeling of latent motion that was constantly developing. The steel sheets she made use of were constructed on the basis of careful calculations, measurements and plans and assembled with bolts thus giving form to compositions which unwind rhythmically in various directions, with either a horizontal or vertical development, and created the impression of eternal movement.

Until practically the end of the Fifties, Natalia Mela made works primarily on commission, as well as a series of busts that faithfully reproduced her lessons at the Athens School of Fine Arts. In 1960 she abandoned the use of marble and stone and turned to metal, adopting at the same time a style freer and more abstract. Animals and birds, as well as mythological figures in dynamic poses, rendered schematically, but done with a roughly-worked surface with the later addition of pieces of metal to form linear constructions in space, were thus transformed into symbols of a natural demonic power. In her most recent work her interest has remained focused on figures from the animal kingdom, but her materials have been enriched. “Owl” is a characteristic example of her work these past few years and her turn to compact figures with the use of new materials. Static, with an intense look to them, eyes stressed and formed of two inset marbles and using angular contours, she brings to realization, exercising a contemporary eye, the ancient symbol of wisdom.

![Fortress Aigosthena [pt. Porto Germeno], Lithographic Reproduction of Drawing Published in the Journal “Zeitschrift fur Bauwesen”](https://www.nationalgallery.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/75331_2000_2000-734x1100.jpg)

![Fortress Eleftherai [pt. Kriekouki], Lithographic Reproduction of Drawing Published in the Journal “Zeitschrift fur Bauwesen”](https://www.nationalgallery.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/75330_2000_2000-664x1100.jpg)

![[National] School of Chemistry, Corner of Solonos and Mavromihali Streets, Main Facade, Cross Section, Original Shape before Additions](https://www.nationalgallery.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/75327_2000_2000-1730x1100.jpg)

![Vallianios [National] Library.](https://www.nationalgallery.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/75326_2000_2000-1920x1073.jpg)