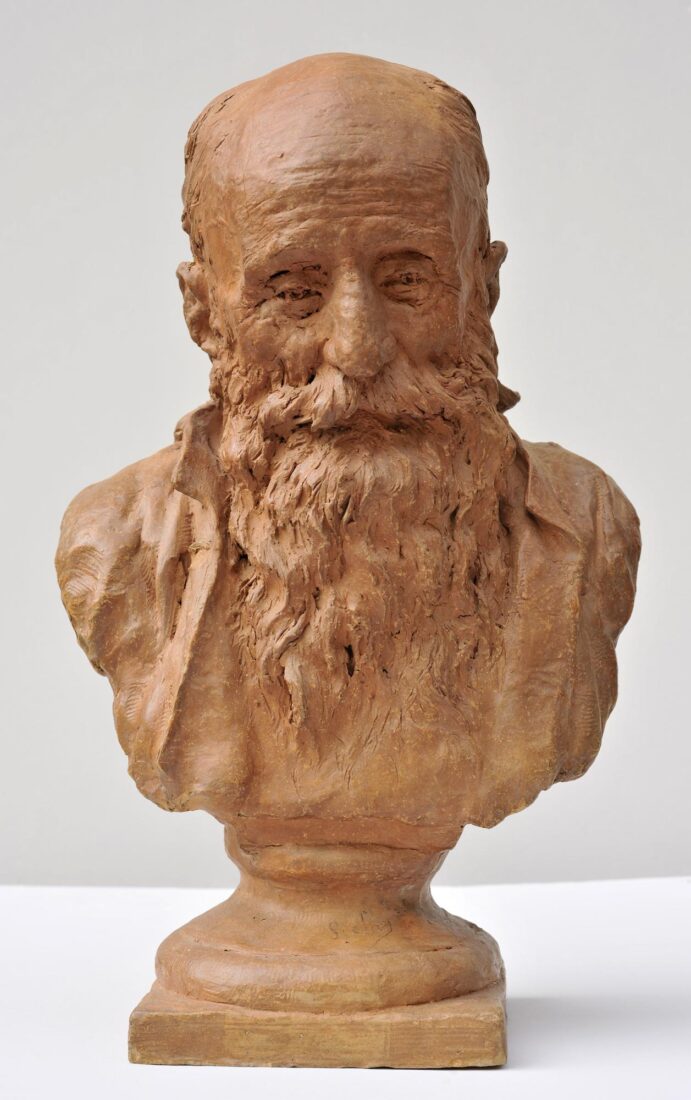

Thomas Thomopoulos was one of the last Greek sculptors to do post-graduate work in Munich, during a period when most other artists had already turned to Paris. This fact, however, did not prevent him from nourishing a deep admiration for the sculpture of Rodin and to be considered during his time as the “introducer of the Rodinian School in Greece”. His work combines academicism with symbolism and romantic tendencies, which are all derived from the French artist’s style, while in a number of compositions he also adopts a realistic form of depiction.

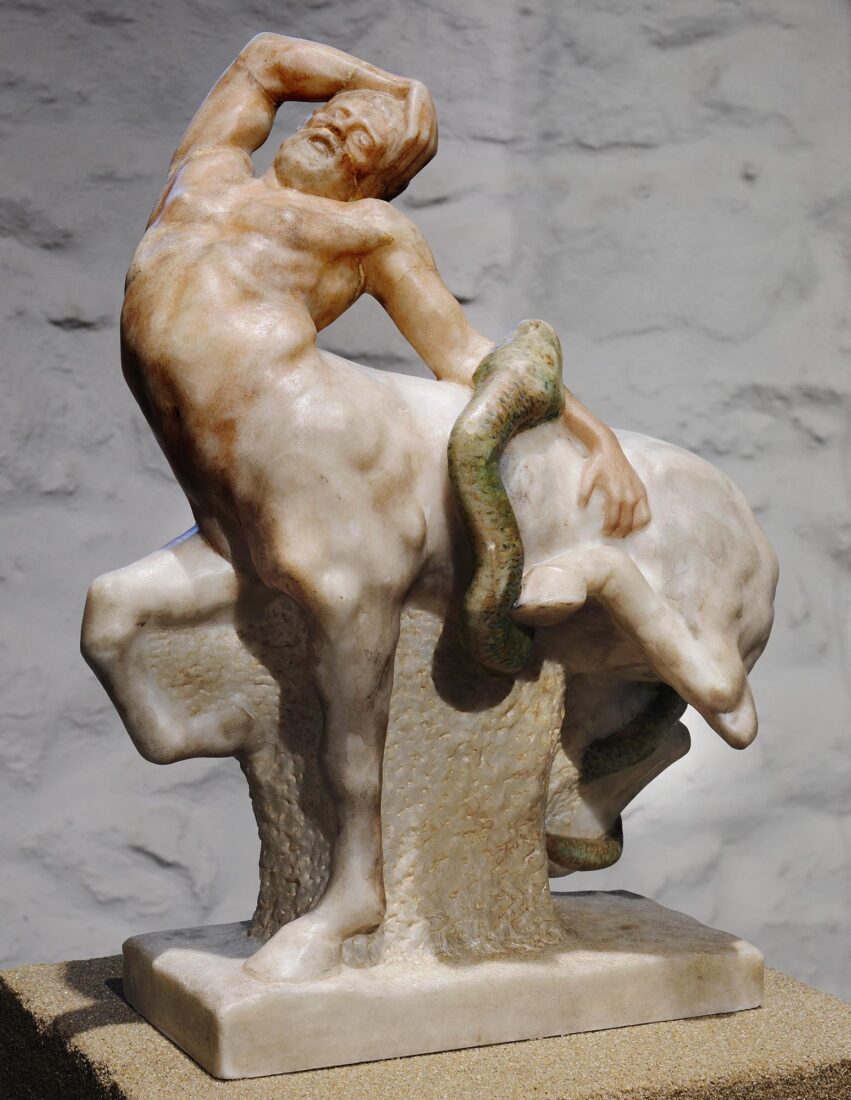

“Centaur” is a work inspired by Greek mythology, an echo, perhaps, in terms of theme, of “Female Centaur” (circa 1887) by Rodin. The “Centaur” is depicted at a moment of crisis, as a snake has wrapped itself around his body. His reaction to the deadly attack is shown by the contraction of the body backward and his right hand brought to his brow, a pose obviously based on the Hellenistic Laocoon group. Conversely, the fluid and soft surfaces and the naturally evolved base which also acts as a support, reveal the influence of Rodin’s plastic perceptions. The sculpture was painted using the encaustic method, as were quite a few of Thomopoulos’ works, who introduced this innovation around 1900.

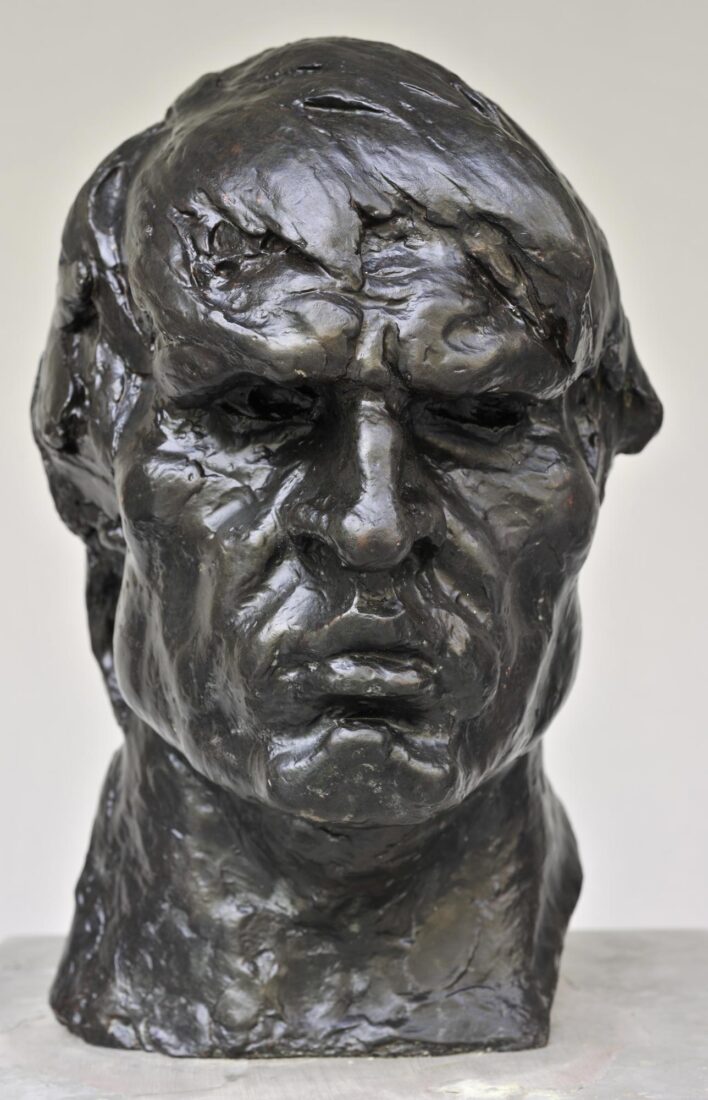

Constantinos Dimitriadis could be characterized as Rodin’s most consistent representative in modern Greek sculpture. He adopted the French artist’s style of modeling forms and used the same subject matter as a point of departure.

“To the Dreams Left Behind and Defead” is a characteristic example. It was to have been the central scene in a larger iconographical sculpture group titled “Life’s Defeated”. Nine individual scenes were to comprise the whole, references to the failures, disappointments, dilemmas and efforts of ordinary human beings in the course of life.

Dimitriadis carved two versions of “Dreams Left Behind and Defeated”. In the first, an unseen figure covered by the veil of Destiny rises up to envelop a couple. The second version is on display in the National Glyptotheque.

The powerful, muscular man, here, seems to have surrendered to his fate. His facial expression imparts a sense of forbearance, perhaps even reverie. The woman, curled up as if seeking protection, leans towards her companion.

The man’s well-defined musculature and the woman’s soft curves are elements that characterize many of Dimitriadis’ works and reveal the influence of Rodin’s views on modeling forms. The same is true for the heavy, unrefined block of marble that frames the figures, allowing them to emerge as nearly carved in the round.

Costas Dimitriadis was the most committed exponent of Rodin’s style in Modern Greek sculpture. He adopted the latter artist’s style, with whom he shared a common thematic starting point, especially in his free compositions. What might be characterised as his most innovative contribution to Modern Greek sculpture is also owed to Rodin’s influence: He established the fragmented figure as an autonomous, complete work.

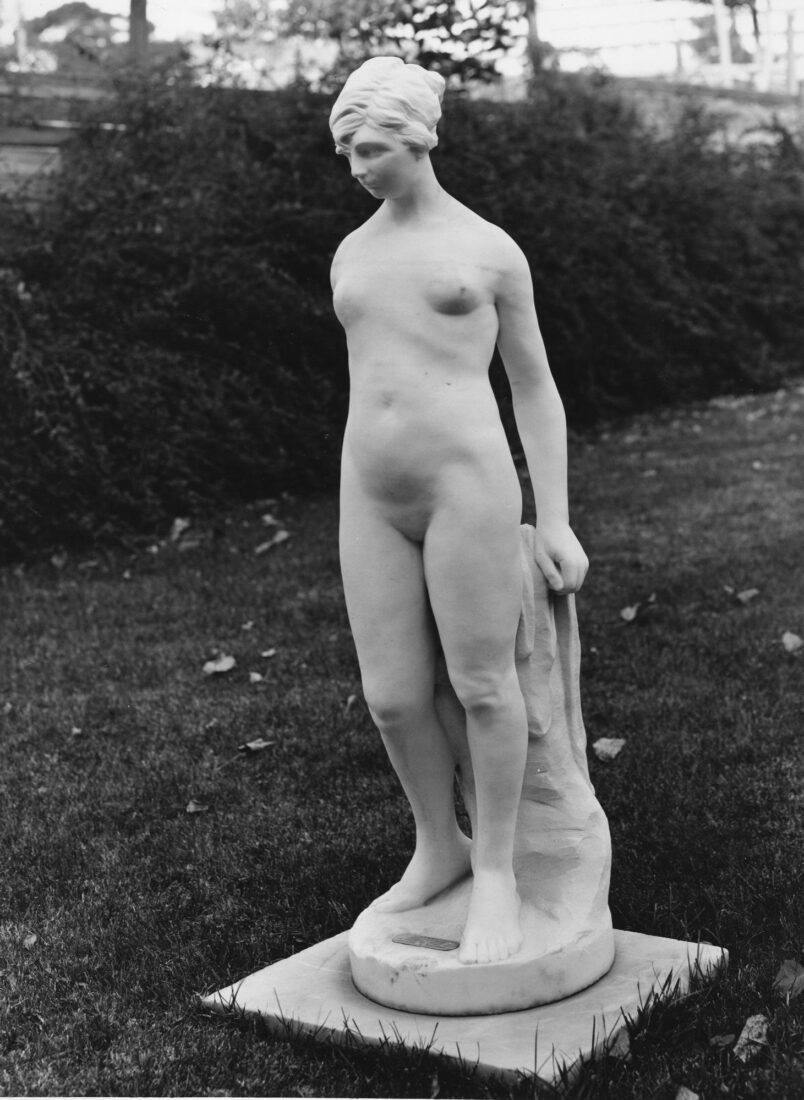

Prominent place among his free compositions enjoy his nude female figures, either whole figures, or not. His “Nude Woman” (or “Dancer”) is a typical work, in which, echoing Rodin’s “Woman-Centaur” (c. 1887), with the tense twist of the torso and the arms spread out in exasperation in front, the artist captures a fleeting dancing movement. The torso of this sculpture later became an autonomous work, on which Dimitriadis worked in various sizes. The version in the National Gallery collection went on display at the Venice Biennale in 1936 and is the sculpture which launched the museum’s sculpture collection, in 1933.

Kostas Dimitriadis could be characterized as the bearer par excellence of Rodin’s style into modern Greek sculpture. He adopted not only his plastic style but also the same subjects as his starting point, especially in his commission free compositions.

Among his non commissioned compositions, a most eminent place was occupied by nude female figures. The “Nude Woman” (or “Dancer”) falls within the range of his interests, while the model was the famous dancer Stasia Napierkowska. Dimitriadis, who was particularly interested in the rendering of the momentary, the fleeting, is here endeavoring to render the fleeting movement of the dance, which at the same time offers him the possibility to demonstrate his ability in the rendering of anatomical details. However, one must not overlook the iconographic model used here, the “Woman-Centaur” (c. 1887) by Rodin. Dimitriadis borrowed the intense twisting of the body and the desperate stretching of the arms ahead, thus largely negating their dramatic content, and transformed them into the harmonious and graceful movement of his own dancer.

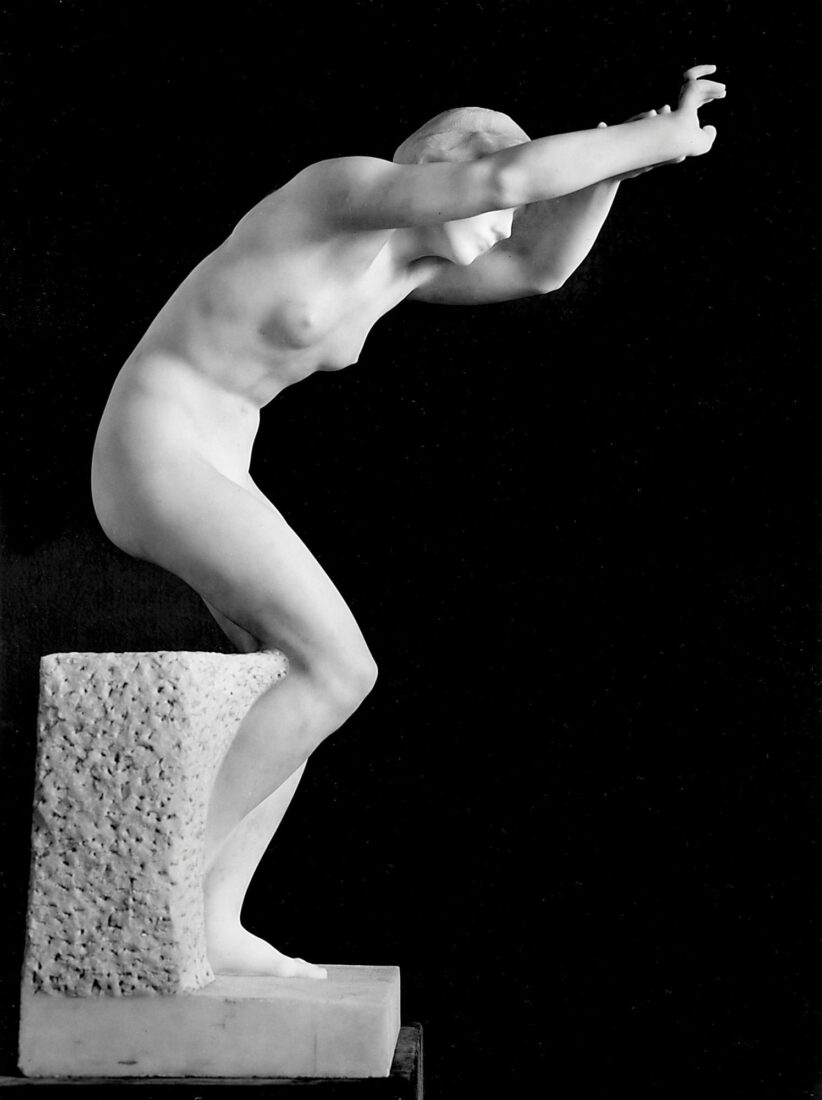

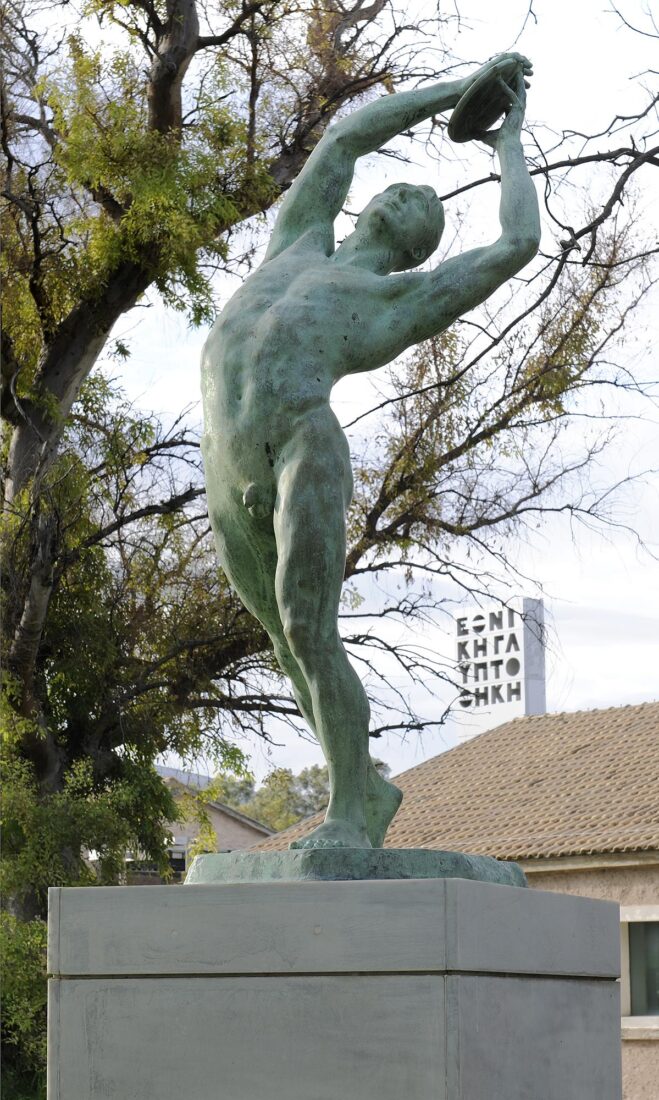

The “Discus-Thrower” is one of Dimitriadis’ mature works, one of the most characteristic of the way in which he rendered the nude male body. Made in 1924 and exhibited in Paris in the framework of the Olympic Games held there, it won the sculpture prize. The following year the entrepreneur, Euripides Kehayias, a Greek from America, bought it and gave it to the Municipality of New York City, which placed it in Central Park. Another copy was placed in the Dijon stadium in France and a third in Athens, in 1927. The copy exhibited at the National Glyptotheque was cast in 1989 from the plaster model which belongs to the National Gallery.

The dexterity of the artist in the moulding of the nude body, already evident in his earlier works, has now reached its acme. The athlete is depicted at precisely the moment before the toss, in a carefully calculated stance, while his swollen veins and his nerves, that are outlined, reveal his total concentration just before the final endeavor and place an emphasis on the momentary. The work spreads out and dynamically occupies space, while the variety of opposition displayed by the limbs, makes it possible for the composition to be viewed from all sides.