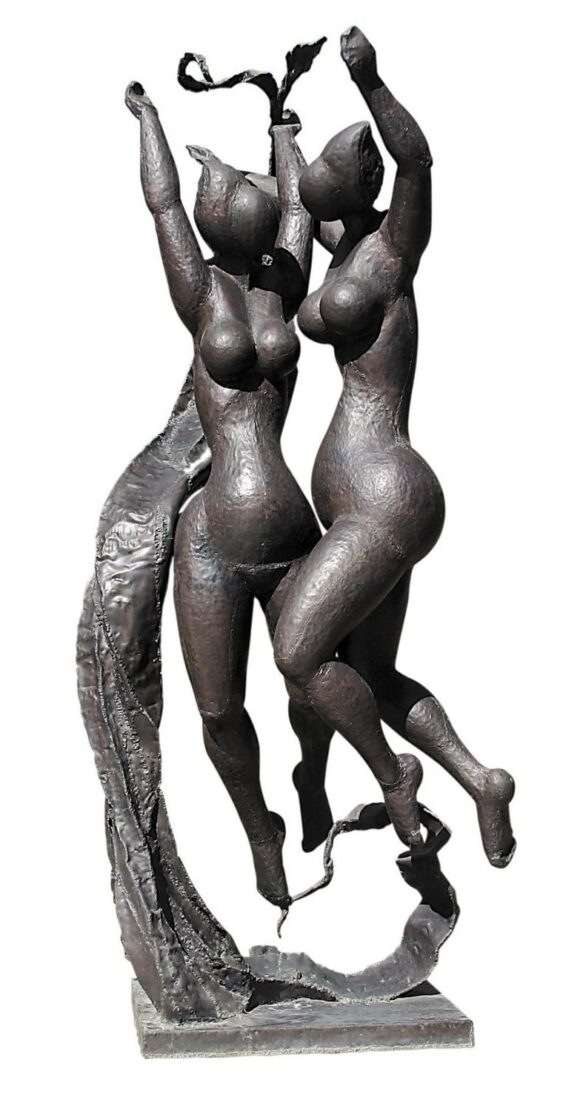

His focus consistently on the human figure, Christos Kapralos fashioned his own personal style through the assimilation of the doctrines of ancient Greek and folk art as well as those of the European avant garde. He made his first works of clay and plaster, realistic but at the same time simplified and pure. When he turned to the use of bronze in 1957 the human body was transformed into Nikes and mythological figures, ancient warriors, couples, mothers and children.

In 1965 Kapralos began using wood, eucalyptus trunks in particular. This gave him the opportunity to create compositions powerfully schematic and strongly non-figurative, obedient to the form imposed on him by the shape of the trunks themselves. Thus, he created a series of works inspired by the events and figures of antiquity, such as “Warrior”, a theme which had occupied him since the Fifties. In contrast, however, to the dramatic intensity which characterized the older compositions in bronze, the “Warrior” made of wood acquires a monumental character and thus is transformed into a symbol of Victory.

Antonios Sochos was one of the first sculptors to distance himself from neoclassicist doctrines and turn in a completely different direction. His study of archaic plastic art from the 7th and 6th century BC, of Cycladic figurines, as well as Gothic art, coupled with his initiation into the long tradition of folk sculpture on Tinos in combination with an acquaintance with the avant garde movements in Europe were the sources of his inspiration.

“Girl” is a work that makes a clear reference to early archaic sculpture, to effigies and even to Egyptian art. The pose assumed by the young figure, frontal and static, practically without depth, points to a distant model in the “Lady of Auxerre” from the 7th century BC and “Hera by Cheramyes” from the 6th. The right hand, holding the folds of the garment, is the only element breaking the absolute immobility, while the surfaces are for all intents and purposes flat, with the exception of the emphasis on the chest, the light grooving suggestive of drapery and the engraved decoration on the bottom part of the tunic. The carving was done directly on eucalyptus wood. The use of wood in a large number of Sochos’ works is a further indication of the artist’s innovative thrust and connects him both to the folk sculptors who made figureheads for ships and the primitivist perceptions which then held sway in Europe.

A sculptor who centered his attention on the human figure, faithful to representation but with a strong tendency toward the schematic and the abstract, Memos Makris studied at the Athens School of Fine Arts, and then attended lessons in the studios of Jean-Paul Laurens and Marcel Gimond in Paris, where he lived for five years, settling in Hungary in 1950. Busts, female figures, nudes, and monuments designed for public spaces, made up the core of his work, which drew elements from both archaic art and his French teachers and, occasionally, abstract and expressionist models.

In 1965 he began working on a number of naked figures. These figures are rendered very schematically, with oval heads and sometimes with the characteristics of their physiognomy simplified, and other times without any characteristics at all, with the bodies all worked the same way, with rounded volumes and elongated forms. The “Spring Dance” follows along these lines, but the abstract rendering is even greater, while the two figures hover in the air in a laudatory dance in honor of spring, recalling scenes from the three Graces in compositions of European art.

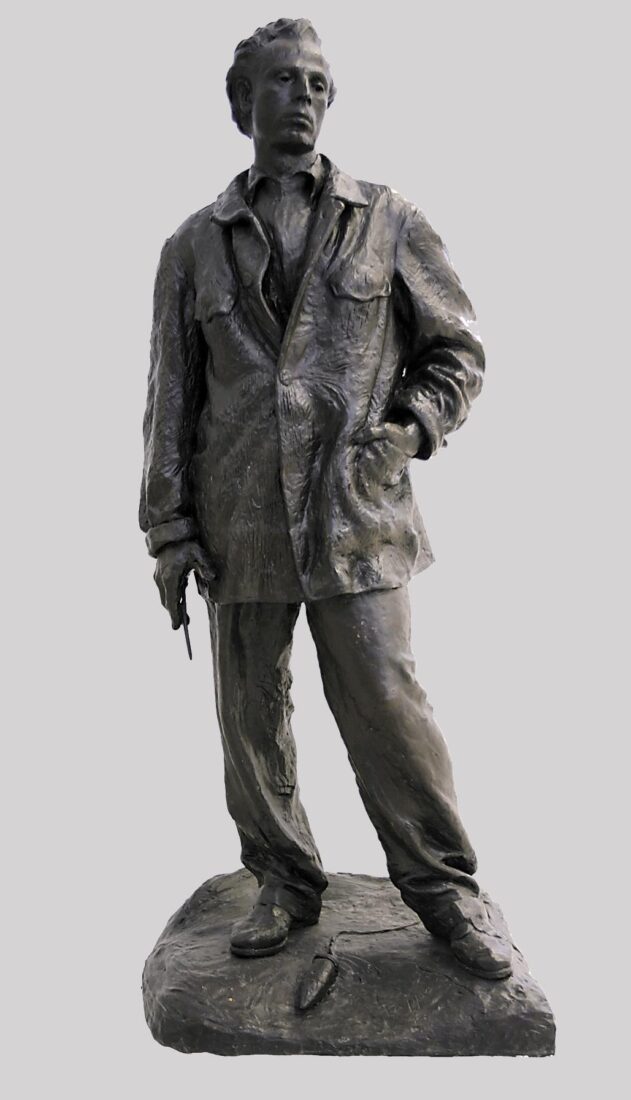

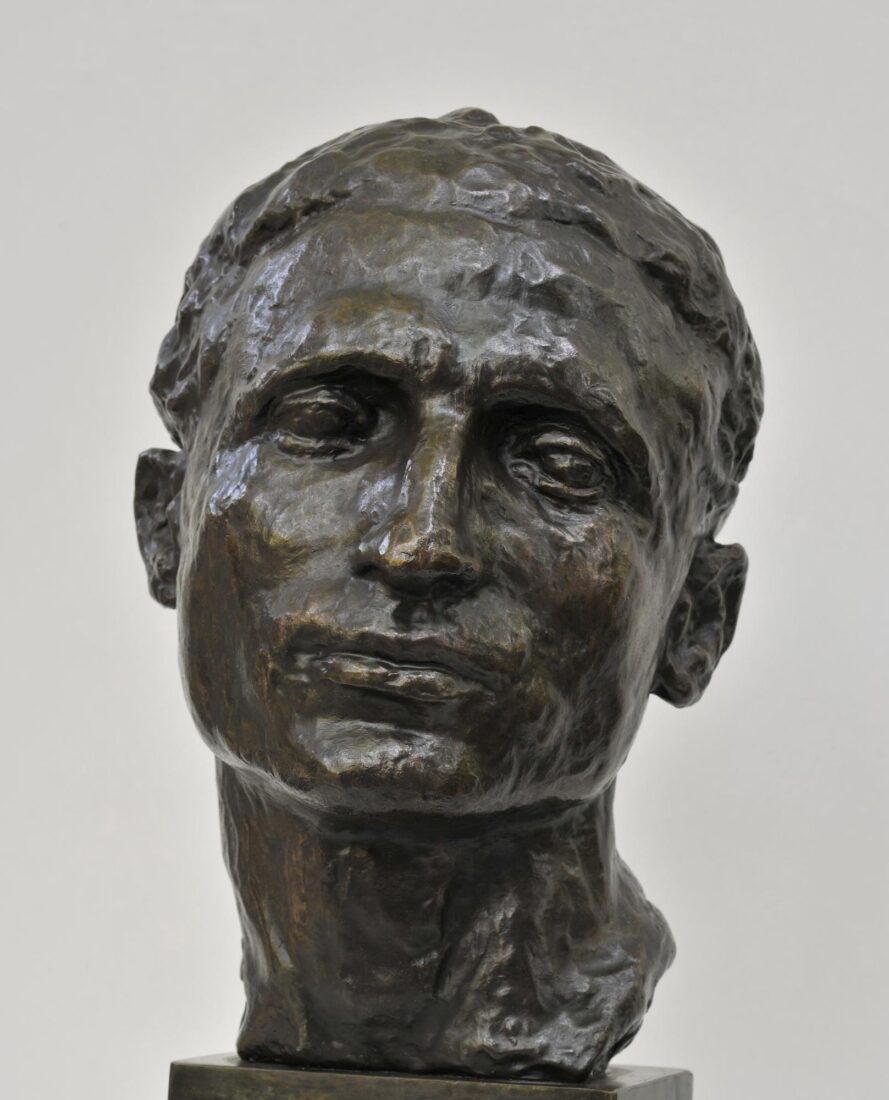

Yannis Pappas remained faithful to the figurative depiction focused on the human being throughout his entire artistic career. Guided by nature and tradition he moulded, drew and painted the human figure, initially placing his stress on a realistic and detailed rendering and eventually seeking to express the essence of the subject, using a simplified and more abstract manner. His style echoes both archaic Greek and Egyptian sculpture, as well as the contemporary trends.

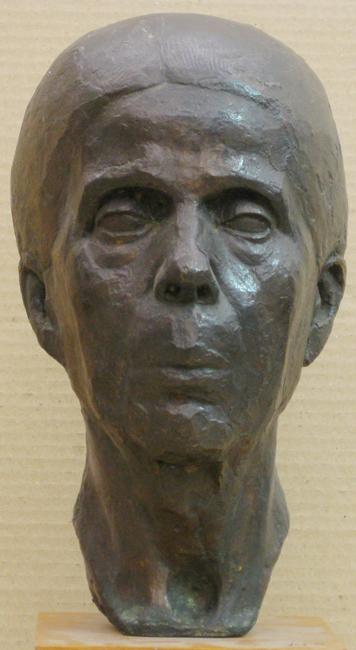

During his stay in Paris he made the sculptures of Christos Kapralos (1936) and Yannis Moralis (1937), two very characteristic early works. The differences in the rendering of these works indicate the style that he will adopt in his later compositions. While Kapralos is characterized by intense realism, Yannis Moralis’s sculpture is characterized by the essential and the details are stressed in a discreet and selective manner in specific parts of the face and the body. Thus they forewarn the more abstract style which will characterize his later works.

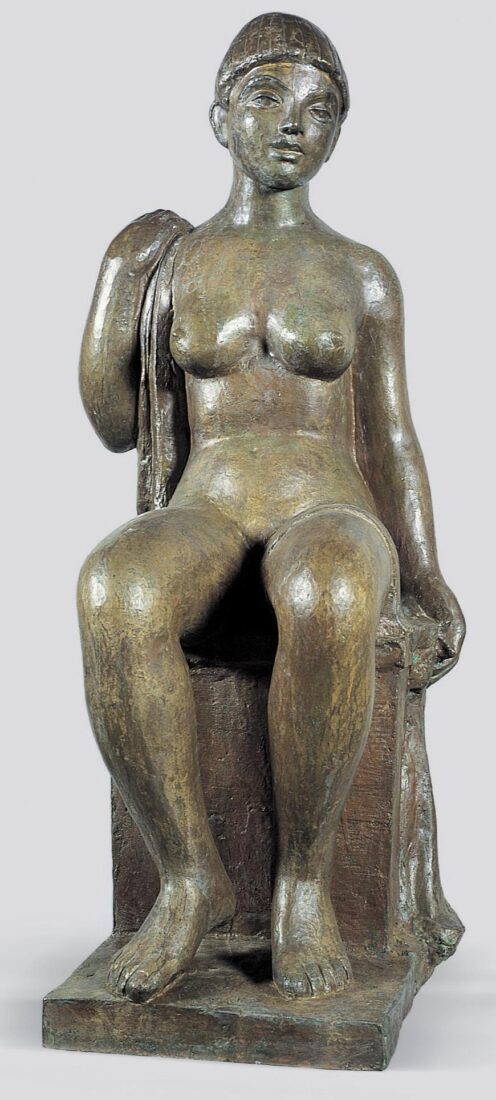

Titsa Chryssochoidi, a student of Thomas Thomopoulos, Thanassis Apartis and the French sculptor Robert Wlerick, belongs among those Greek sculptors who served as conduits par excellence for the style of Aristide Maillol. The female figures, the dominant theme of her work, are usually rendered nude, reclining, seated or half-reclining, with lavish and gentle curves, stable and assured outlines, simple arrangements, a tranquil even languid pose and an otherworldly expression. All these reflect the style of the French artist which Chrysochoidi adopted and adapted to her own perceptions.

The seated “Nude” at the National Gallery is a characteristic example of her personal style which not infrequently reveals a romantic temperament.

Michalis Tombros was a leader in disseminating avant-garde European currents in Greek art. He lived and worked in Paris from 1925 to 1928, yet he had visited the French capital three times already. This three-year stay in the French capital was decisive in shaping his enterprise. The influence of Rodin’s descendents is recognized in many female figures that were created during that period. The “Stout Seated Woman” is a characteristic example. A woman with ample curves does not represent the physical ideal, but adheres to the prototype of similar figures by Aristide Maillol. The views of the French artist on the modeling of the female nude were decisive for both Tombros and other Greek sculptors as well. Thus the figure, with an expression of anticipation and forbearance is conveyed in a closed, compact form with robust curves and a clean outline. Without becoming consumed in descriptive details, the artist shapes large, clear volumes with no voids, creating a solid piece that imposes itself on the space with its stillness and calm.

Antonios Sochos was one of the first sculptors to distance himself from neoclassicist doctrines and turn in a completely different direction. His study of archaic plastic art from the 7th and 6th century BC, of Cycladic figurines, as well as Gothic art, coupled with his initiation into the long tradition of folk sculpture on Tinos in combination with an acquaintance with the avant garde movements in Europe were the sources of his inspiration.

“Head of Kore”, carved directly into porous stone, with the beautiful features, the expressive face and the slight but thoughtful frown, makes it obvious that he drew his inspiration from the “Kores” on the Acropolis. The frontal rendering, the lips, the eyebrows and the pupils of the eye which are lightly made-up, the stylized hair-style which softly frames the face and even the material itself, connect this work to the figures of archaic plastic art, while the incorporated base, which creates a compact volume with the head and the neck, serves as a reference to ancient hermaic steles.

Yannis Pappas remained faithful to the figurative depiction focused on the human being throughout his entire artistic career. Guided by nature and tradition he moulded, drew and painted the human figure, initially placing his stress on a realistic and detailed rendering and eventually seeking to express the essence of the subject, using a simplified and more abstract manner, which echoes both archaic Greek and Egyptian sculpture, as well as the contemporary trends.

During his stay in Paris he made the sculptures of Christos Kapralos (1936) and Yannis Moralis (1937), two very characteristic early works. The differences in the rendering of these works indicate the style that he will adopt in his later compositions.

Making use of a completely realistic approach, Pappas moulded Christos Kapralos in an open and relaxed composition, in which the spontaneous and well-balanced pose, the placement of the hands, and the clothes, the head slightly turned, and the expression on the face, are all combined together in order to render this unsophisticated young artist who was in the French capital and, despite his hesitations and fears, had the hope of succeeding and the temperament to accomplish it.

Nikos Perantinos remained faithful to an anthropocentrically conceived depiction, in agreement with the classicist perception, during a period in Greece when quite a number of artists had begun to turn to non-figurative or even completely abstract shapes. Busts and full-bodied statues, whether from free inspiration or commissions, made up the largest part of his artistic work.

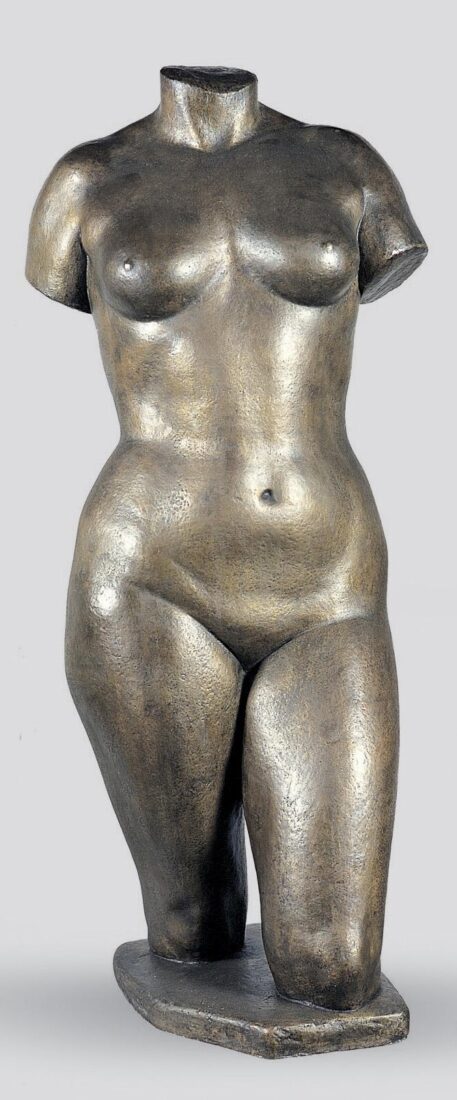

“Torso”, which is based on his wife, Olympia, is part of a series of works, starting in 1938 with “Olympia”, where the torso is shown with the head. In 1939 the plaster model was made of the work at the National Glyptotheque. In subsequent versions, the main theme is sometimes retained untouched and other times becomes part of a statue, full-bodied or not, with or without a head and limbs and with small variations in the manner of moulding, arriving at the final full rendition in 1960.

The vigorous female body, imposed on space with her dynamic presence, the clear contours and the harmonious moulding, refers back to a sculptural perception of form as it is expressed in the works of Aristide Maillol and reveals the idealistic outlook that more generally distinguishes Perantinos’ sculpture.

Student of Antoine Bourdelle, Georgios Kastriotis remained faithful to an “anthropocentrically” focused depiction. Though from his teacher he retained the doctrines regarding the rendering of surfaces, the clarity of drawing and the love of impulsive movement, during his career he formed his own particular style which combined realistic rendering with symbolism, or even allegory.

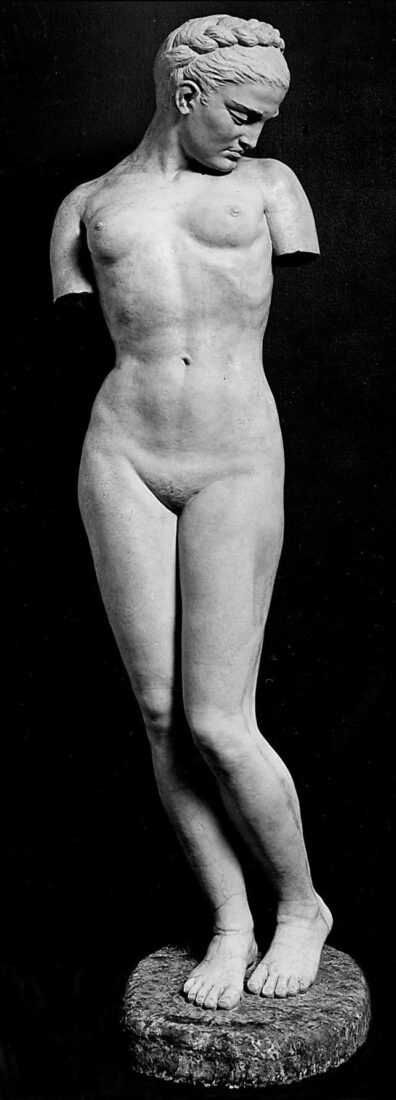

“Modesty” is part of a thematic cycle, where the nude or semi-nude female figures function as symbols or allegories. The young woman with the finely-drawn body and whose head is turned left and lowered with a bashful glance, produces the type of virginal beauty which stirred the artist‘s interest in quite a number of cases. Her arms severed high above the elbows reveal at the same time a tendency to associate this sculpture with the beauty of ancient statues and the fragmentary figure, which Rodin first made into an independent work of art.

A sculptor from Pergamos in Asia Minor, Vassos Kapantaes made the land of Ionia the center of his work. Using elements from the art of the archaic period, folk art, as well as modern tendencies, he creates works such as “Asia Minor Ma”, inspired especially by the history of Asia Minor.

Ma was an ancient goddess with a multiplicity of meanings, while in “Supplicants” by Aeschylus lent her name to Earth, the mother of everything. Here she is rendered as a fragmentary female figure, bearing a dramatic expression as if it were a mask from the ancient theater and an archaic hair-style that increases her dramaticness. Being depicted as static, without arms and with her legs cut-off, constitutes the personification of the artist’s own amputated paternal land.

In the mid-Thirties, Apartis turned his interest to the making of animal sculpture, studying at the Paris Zoological Garden. Occupied since then, from time to time, with the same subject, in 1955 he made “Female Dog”, using “Duchess”, the dog of a neighbor in Paris, as his model.

The animal, despite the fact it’s motionless, gives the impression of being in a state of complete preparedness, with its pricked ears and muzzle jutting. Guided by ancient art, but having a living model before him as well, Apartis did not expend himself in descriptive details, but moulded a sturdy body with smooth surfaces, under which is outlined the powerful skeleton. The animal’s pose, with its legs parallel to each other, the slight turn of the head to the right and the tail touching the legs, as well as the moulding of the sturdy body itself, bring to mind one of the most important works of ancient art, namely the Etruscan “She-Wolf” in the Capitoline Museum (500-480 BC), while the jutting head had its, albeit distant, model of a dog from the Sanctuary of Artemis in Vravrona (530-520 BC), now in the Acropolis Museum, which, with its body tensed and its legs spread, is ready to attack.

Apartis made this relief stele in response to a commission for a monument to the Boy Scouts of Smyrna, who had been tortured during the Asia Minor Disaster. But in the end the memorial was not approved by the commissioners because it depicted a naked male figure. In 1983 the relief, incorporated into the copy of the iron door of a cell, was used for the composition of a monument in honor of the patriots who were tortured during the German Occupation, in the holding cells of the Gestapo. The composition also bears the titles “The Prisoner”, “The Martyr”, “The Victim”, “On Execution” and “So the Land You Walk upon Will be Free”.

Apartis, wanting to make a work that would symbolize all the young men who sacrificed themselves for an ideal, combines elements from Maillol’s “Bicyclist”, from ancient funerary steles, as well as the inclination of the head which, in works by Michelangelo, Rodin and Bourdelle expresses inner anguish and death.

Thanassis Apartis was the first of several Greek sculptors to study under Antoine Bourdelle. The teachings of the latter and other descendents of Rodin and the simplicity of Archaic sculpture shaped Apartis’ style.

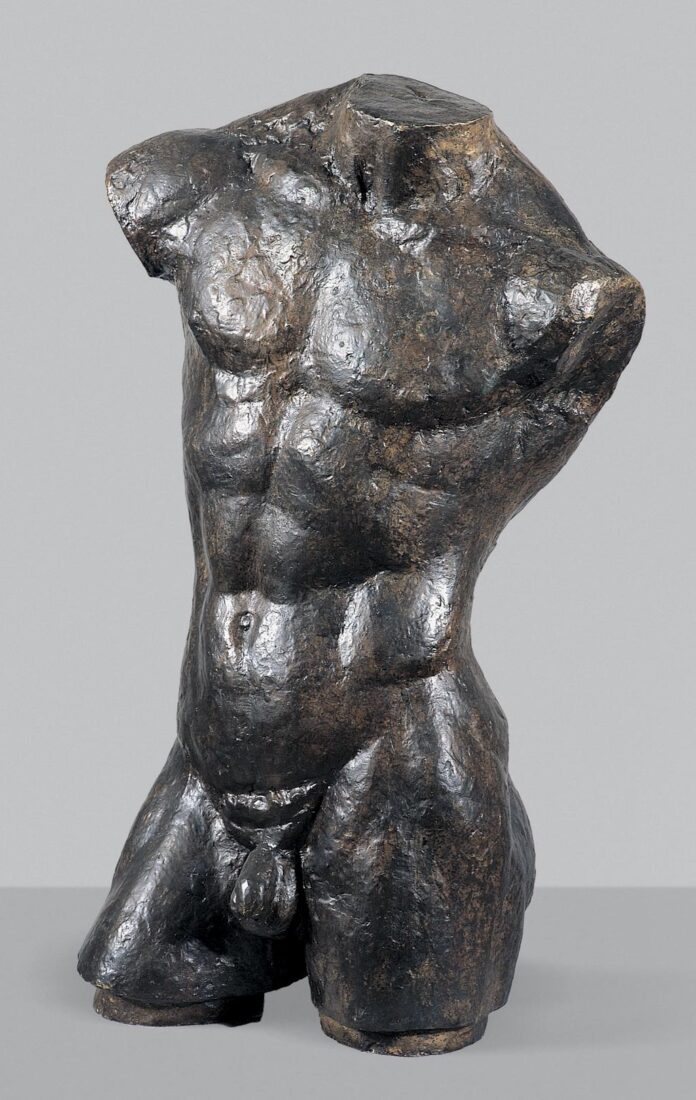

In 1921, while still a student, Apartis made the “Torso of a Portuguese Man” in a characteristic contrapposto pose, using a Portuguese aristocrat as his model. He worked on the piece for three months under Bourdelle’s close supervision and frequently productive interventions. In fact, Apartis himself considered it a milestone in his creative progress.

It should be noted, however, that Apartis did not render the “Torso of a Portuguese Man” with characteristic Archaic simplification that characterized his later work. The pulsating surfaces and fragmented treatment in this case brought him closer to the work of Rodin, whom the Greek artist admired immeasurably. Rodin was the first sculptor to intentionally produce a limbless torso as an autonomous work. In so doing, he bestowed an independent quality on the imperfect figure, stressing its expressive force through its modeling and the deliberate omission of its limbs.