The full-length male figure, heir to the ancient Kouros, dominates Joannis Avramidis’ oeuvre. However, his is a figure that is stripped of every descriptive detail. Schematized, it stands upright, self-contained, imposing and static, like an ancient column.

The solitary figure-standard, as of 1959, constituted the core of his group compositions. The figures create a unit and frequently result from the revolving of the ancient figure around its axis. In this manner, Avramidis conveyed the idea of the ancient Greek “Polis” (City-State) in his sculpture of the same title. The repetition of the ancient figure nine times creates a compact group of identically-sized figures with like features. The piece thus personifies the idea of a community in which all its citizens are equal.

Dionyssis Gerolymatos is one of the few sculptors still working in the traditional sense, that is, he works with hard materials – stone, marble, cement. His thematic field includes works taken on commission as well as compositions of free inspiration, small or large. Since his student years, he has made use of extreme schematization, which, in his later works, is sometimes transformed into abstraction. Employing an expressionistic or surrealistic style, he gives form to thoughts, feelings, and impressions, while frequently poetry is also a motivation behind compositions through which he illustrates verses.

The “Stone of Patience” is a characteristic example, where a line from George Seferis is taken as the title of a work, while other of the poet’s verses are engraved on the side. Using stone, a hard material, Gerolymatos combines the external volume, left deliberately rough, with a piece ground smooth which then takes on the schematic form of a bird with open wings – symbol of freedom and hope – and thus creates his own image, an optimistic one, for the poetic words.

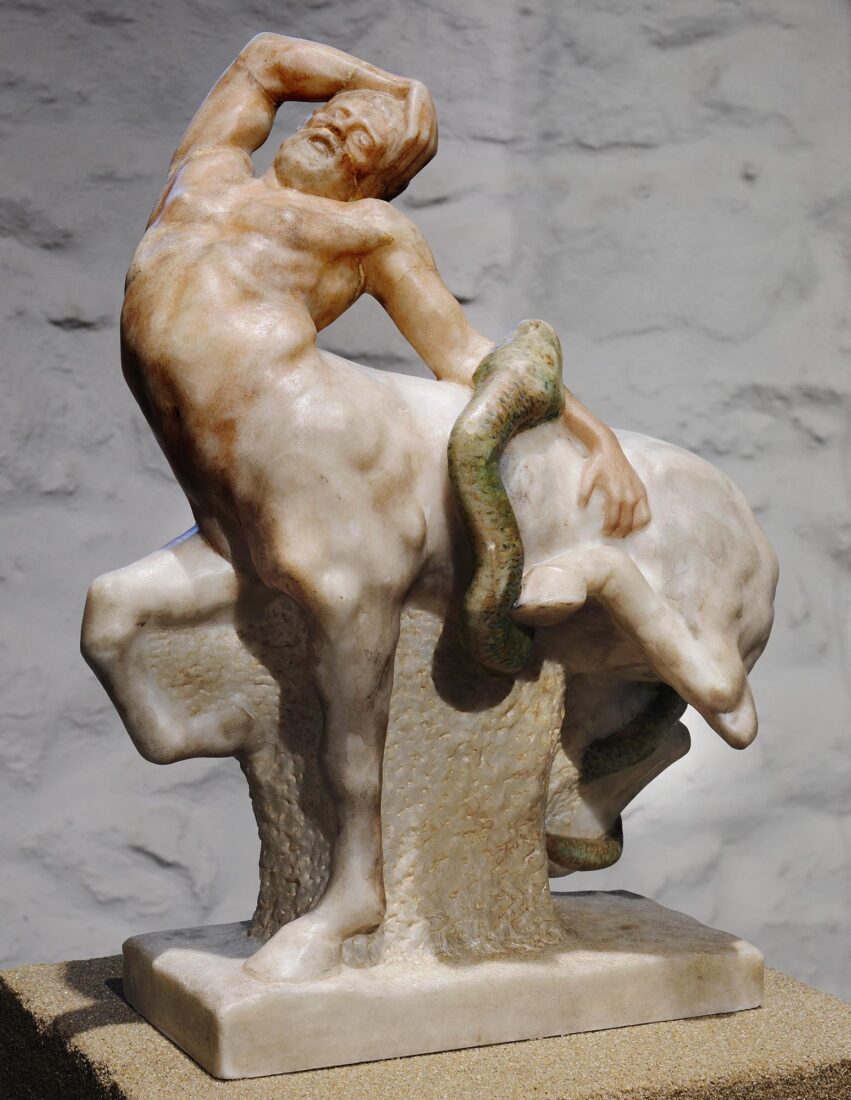

Thomas Thomopoulos was one of the last Greek sculptors to do post-graduate work in Munich, during a period when most other artists had already turned to Paris. This fact, however, did not prevent him from nourishing a deep admiration for the sculpture of Rodin and to be considered during his time as the “introducer of the Rodinian School in Greece”. His work combines academicism with symbolism and romantic tendencies, which are all derived from the French artist’s style, while in a number of compositions he also adopts a realistic form of depiction.

“Centaur” is a work inspired by Greek mythology, an echo, perhaps, in terms of theme, of “Female Centaur” (circa 1887) by Rodin. The “Centaur” is depicted at a moment of crisis, as a snake has wrapped itself around his body. His reaction to the deadly attack is shown by the contraction of the body backward and his right hand brought to his brow, a pose obviously based on the Hellenistic Laocoon group. Conversely, the fluid and soft surfaces and the naturally evolved base which also acts as a support, reveal the influence of Rodin’s plastic perceptions. The sculpture was painted using the encaustic method, as were quite a few of Thomopoulos’ works, who introduced this innovation around 1900.

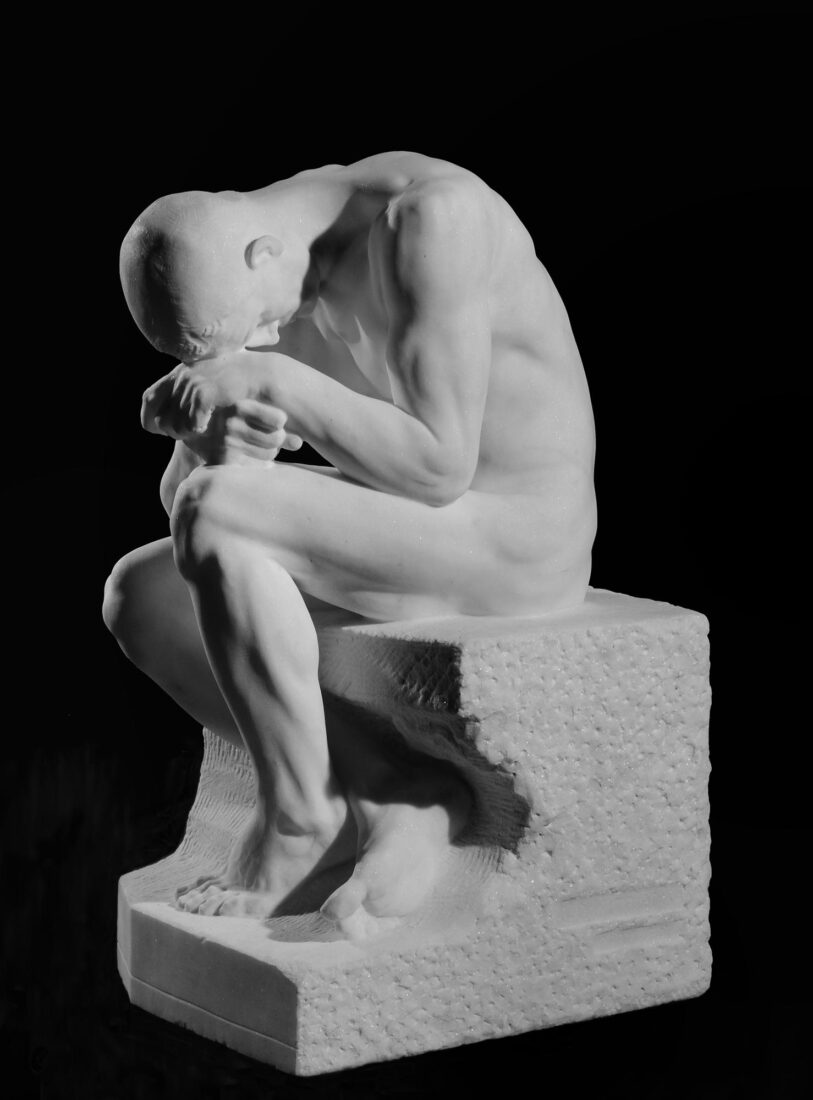

Constantinos Dimitriadis could be characterized as Rodin’s most consistent representative in modern Greek sculpture. He adopted the French artist’s style of modeling forms and used the same subject matter as a point of departure.

“To the Dreams Left Behind and Defead” is a characteristic example. It was to have been the central scene in a larger iconographical sculpture group titled “Life’s Defeated”. Nine individual scenes were to comprise the whole, references to the failures, disappointments, dilemmas and efforts of ordinary human beings in the course of life.

Dimitriadis carved two versions of “Dreams Left Behind and Defeated”. In the first, an unseen figure covered by the veil of Destiny rises up to envelop a couple. The second version is on display in the National Glyptotheque.

The powerful, muscular man, here, seems to have surrendered to his fate. His facial expression imparts a sense of forbearance, perhaps even reverie. The woman, curled up as if seeking protection, leans towards her companion.

The man’s well-defined musculature and the woman’s soft curves are elements that characterize many of Dimitriadis’ works and reveal the influence of Rodin’s views on modeling forms. The same is true for the heavy, unrefined block of marble that frames the figures, allowing them to emerge as nearly carved in the round.

Giorgos Nikolaidis’ sculpture encompasses a broad spectrum of forms, from traditional anthropocentric representations to abstract constructivist compositions, as well as environments and installations. In his earliest pieces he focused on the human figure. The abstract tendency in these works gradually morphed into total abstraction.

In the 1970s Nikolaidis produced a series of sculptures in stainless steel, which he titled with numbers. These works are fashioned from segments of cylindrical shapes with pointed ends that coil freely and dynamically in the space or converge in various rhythmic combinations. The dominant feature is a perpetual circular or spiral movement that is immediately perceptible in some works but latent in others.

“1211A” is a characteristic piece from this series. Starting out from aggressive acute-angled shapes in its lower portion, it evolves into two cylindrical segments that seem to want to form a circle. The piece is incorporated into and coexists harmoniously with the surrounding space. At the same time, the space is defined by the shape and encompassed by it, contributing to the refinement of the sculptural form.

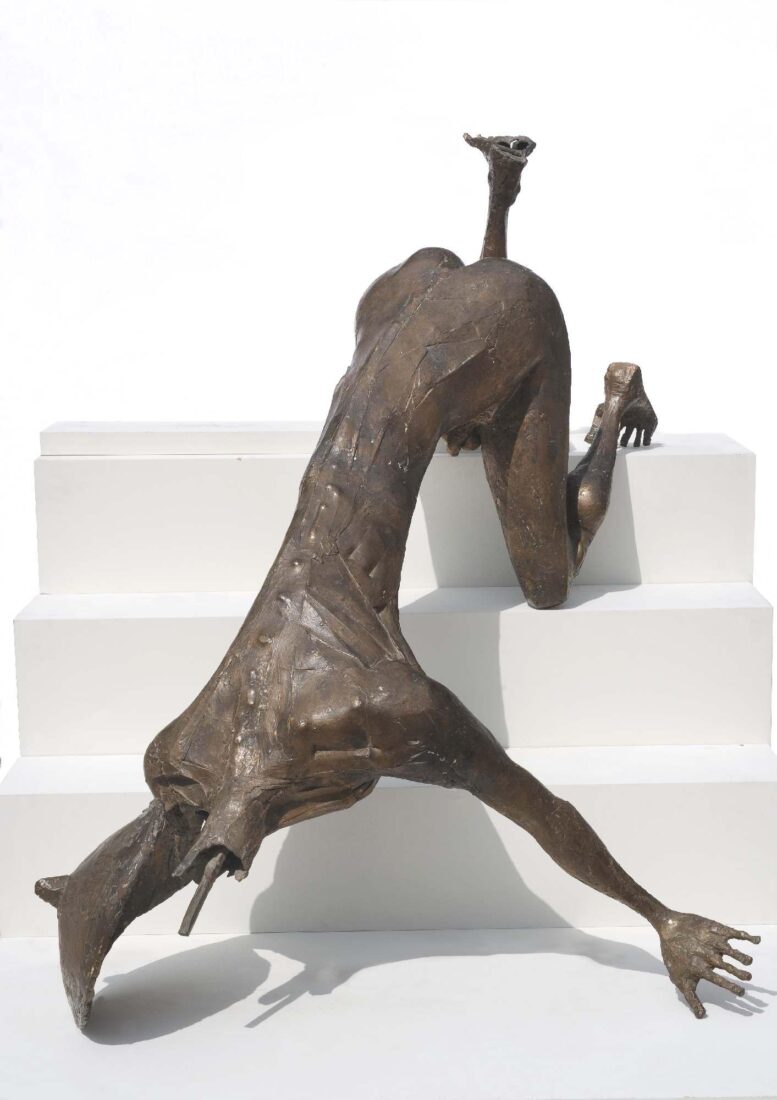

Costas Dimitriadis was the most committed exponent of Rodin’s style in Modern Greek sculpture. He adopted the latter artist’s style, with whom he shared a common thematic starting point, especially in his free compositions. What might be characterised as his most innovative contribution to Modern Greek sculpture is also owed to Rodin’s influence: He established the fragmented figure as an autonomous, complete work.

Prominent place among his free compositions enjoy his nude female figures, either whole figures, or not. His “Nude Woman” (or “Dancer”) is a typical work, in which, echoing Rodin’s “Woman-Centaur” (c. 1887), with the tense twist of the torso and the arms spread out in exasperation in front, the artist captures a fleeting dancing movement. The torso of this sculpture later became an autonomous work, on which Dimitriadis worked in various sizes. The version in the National Gallery collection went on display at the Venice Biennale in 1936 and is the sculpture which launched the museum’s sculpture collection, in 1933.

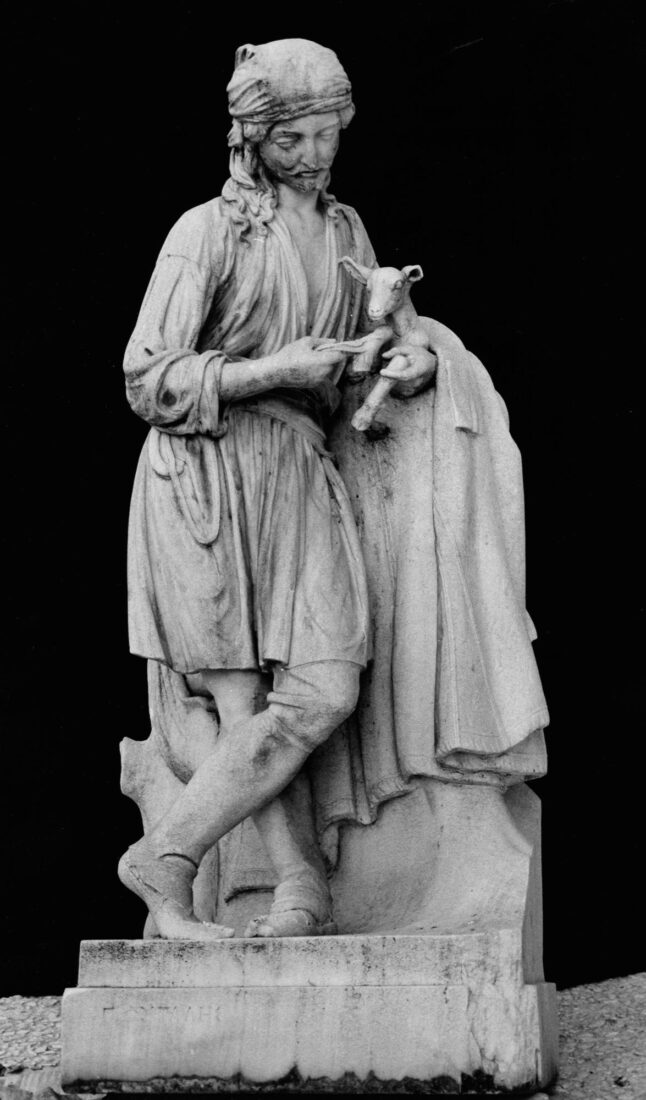

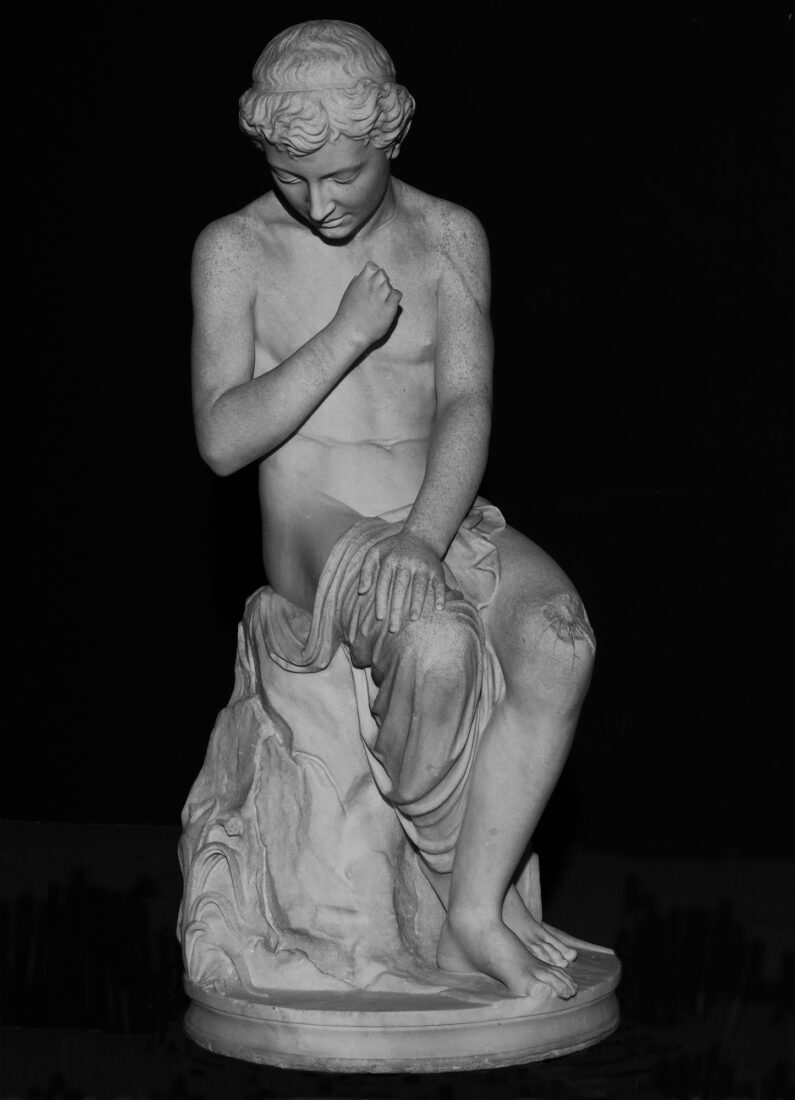

A work that came into the National Gallery collection in 1949, with the bequest of Nicholaos I. Iliopoulos, “Shepherd with Baby Goat” is a characteristic piece by Georgios Fytalis, dating from his period of study at the Athens School of Fine Arts. The work had been submitted at the Kontostavleios competition, in 1856. Both the Fytalis brothers entered the competition, in which their works received an equal number of votes and they shared the first prize. Only Georgios’s work was cast in marble, though.

“Shepherd with Baby Goat” combines the typology of ancient Greek sculpture with neoclassical idealisation, and the meticulous rendition of individual elements with the realistic qualities of an early, for Modern Greek sculpture, genre approach.

A Greek of the diaspora, Philolaos settled in Paris after the war. His liberation from the academic spirit of the Athens School of Fine Arts is obvious even in his earliest work, despite the fact he was still working in the field of representation; he soon consolidated his quests and advanced on to abstraction. The result was compositions based on geometric forms or, in certain cases, on expression by means of non-figurative shapes, in which the figurative elements are limited to a completely schematic rendition. A chance event at the end of the Fifties, when he was trying to give form to a work in iron, revealed to him a physical tendency of the material to undergo centrifugal divergence, leading him to the utilization and the combination of the diagonal with the vertical axis. Thus, using stone, wood, lead, iron and, above all, stainless steel and beton lave, he made compositions such as “The Prow”, which are balanced on vertical and inclined levels, while at the same creating the impression of a potentially revolving movement.

Yannis Gaitis was a restless and inventive man with a strong need to question things coupled with an innate sense of humor. These qualities characterize his art and are embodied in his signature little men.

The little man, a kind of “everyman,” appeared in Gaitis’ painting in the early sixties. He was gradually standardized, schematized and became the protagonist of his compositions, rhythmically repeated in a multitude of combinations. The little man later moved beyond the strict confines of the two-dimensional painted image. He went on to occupy three-dimensional space, decorating furniture and all sorts of everyday utilitarian objects, entered the realm of fashion, and starred in environments and happenings as a finally living human being.

“Mass Transport” is an expression of Gaitis’ critical as well as ironic view of the homogenization, encapsulation and isolation of humankind in urban centers. The double title – “Mass Transport” or “General Transport” – provokes a number of different associations.

Yannoulis Chalepas was a uniquely gifted artist. But his life and artistic development were marked by the manifestation of mental illness that led to confinement in a psychiatric hospital on the island of Corfu and a forty-year hiatus in his artistic production. The first symptoms of aberrant behavior presented in 1878, the same year that he completed his first body of work, referred to by historians as the “first period.”

The “Sleeping Female Figure” is Chalepas’ most widely known sculpture. The original composition was created in marble for the grave of eighteen-year-old Sofia Afentaki in the 1st Cemetery of Athens.

Chalepas based his depiction of the dead girl on the convention of the supine or reclining figure on a sarcophagus or bed. This image originated in ancient Etruria and was particularly popular in European sculpture. Chalepas, however, eschewed total rigidity by flexing the figure’s leg and slightly turning her head. The plasticity of the flesh and the different fabric textures render the work especially lifelike. The girl has a tranquil expression on her face. With her closed eyes and parted lips, she appears to be in a state of abandoned, peaceful sleep. Her pose is completely natural and the drapery folds are executed with exceptional skill. The sole feature evoking the world of the dead is the cross she holds at her breast. This feature connects the work to Greek antiquity as well as to classicistic notions. In ancient Greece, Hypnos (Sleep) and Thanatos (Death) were twin brothers. Neoclassicists saw death as an eternal dreamless sleep.

This cast of the sculpture was made in 1980 in the workshop of the National Archeological Museum. It was an initiative of the then director of the National Gallery Dimitris Papastamos and the mayor of Athens Dimitris Beis in an effort to save certain important neo-Hellenic sculptures from deterioration due to extended environmental exposure.

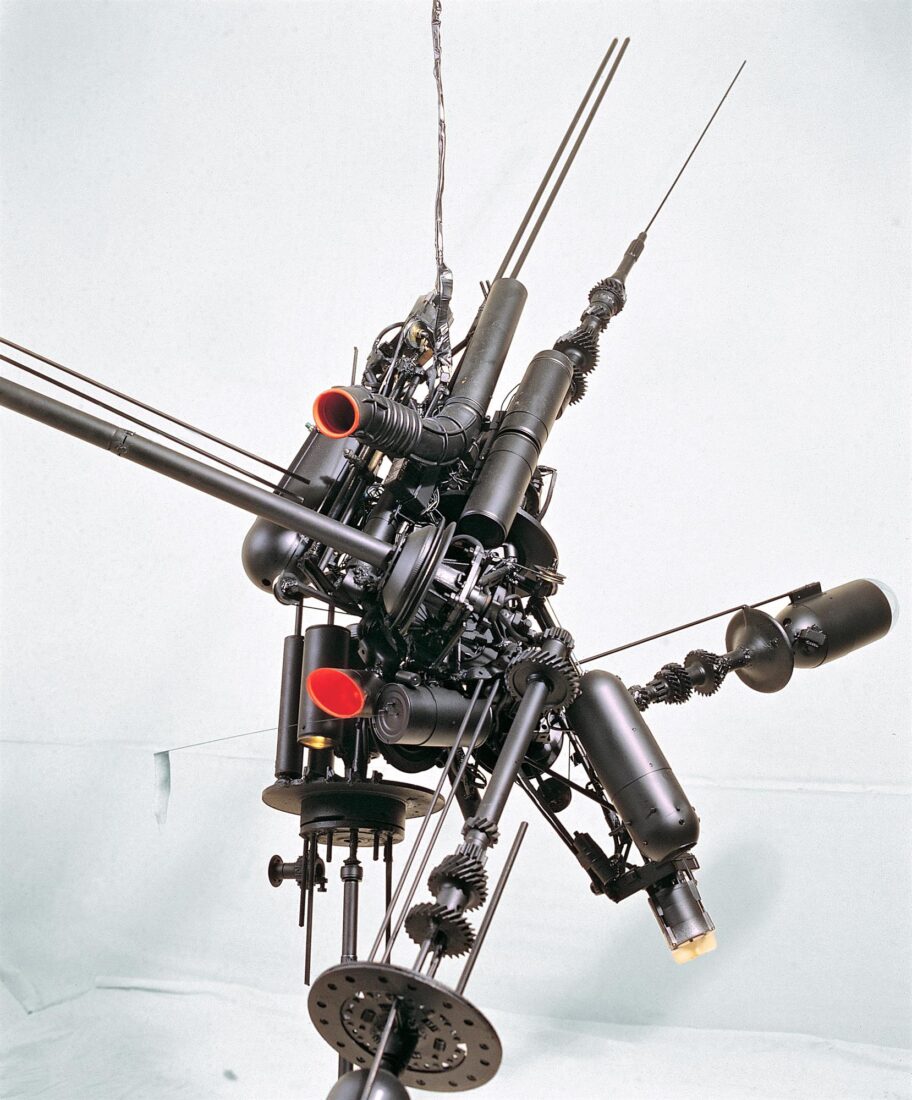

Lambros Gatis studied at the Vakalo School and worked closely for ten years with the engraver Vasso Katraki, but sculpture has always been his principal expressive means. His interest in form and the possibility of the transformation and extension of it through space by means of motion manifested itself at the beginning of the Eighties when he began to create metal constructions assembled from various useless objects and machine parts. These constructions, hanging suspended or on the ground, made with imagination and inventiveness, resemble robots, imaginary beings or peculiar weapons and impose themselves on space by means of mechanical motion and lighting.

“SBBR G” is a hanging electrically-driven construction whose parts turn in various directions, transmit small bursts of light and at the same time emit a strange sound, which might be the sound made by some unknown weapon.

His focus consistently on the human figure, Christos Kapralos fashioned his own personal style through the assimilation of the doctrines of ancient Greek and folk art as well as those of the European avant garde. He made his first works of clay and plaster, realistic but at the same time simplified and pure. When he turned to the use of bronze in 1957 the human body was transformed into Nikes and mythological figures, ancient warriors, couples, mothers and children.

In 1965 Kapralos began using wood, eucalyptus trunks in particular. This gave him the opportunity to create compositions powerfully schematic and strongly non-figurative, obedient to the form imposed on him by the shape of the trunks themselves. Thus, he created a series of works inspired by the events and figures of antiquity, such as “Warrior”, a theme which had occupied him since the Fifties. In contrast, however, to the dramatic intensity which characterized the older compositions in bronze, the “Warrior” made of wood acquires a monumental character and thus is transformed into a symbol of Victory.

Konstantinos Papadimitriou was a folk artist who lived and worked in the 19th century. His works include woodcut figures of War-of-Independence fighters in the popular tradition.

“Georgios Karaiskakis” is depicted in a frontal, serene, but also resolute pose, while the colourisation – a characteristic feature of folk art – accentuates the overall realism. The inscription “This statue of the blessed Karaiskakis was carved and painted by the hand of Konstantinos Papadimitriou, hailing from Agrafa, on June 8, 1829” is also characteristic of the folk culture, not only stating the identity of the portrayed figure, but also the artist’s desire to assert that the work was made by a folk, yet named artist.