Froso Efthymiadi studied pottery-making in Vienna and for a long period made works exclusively in terracotta in a realistic manner. In 1955 she abandoned terracotta and turned to the use of metal, while the realistic rendering began to lessen and the figures became very abstract, but without the physical form itself becoming unrecognizable.

The female figure provided the spark for the creation of a multitude of both small and large compositions which, sometimes static and other times in motion, set forth the personal view of the sculptor in regard to the rendering of female charms.

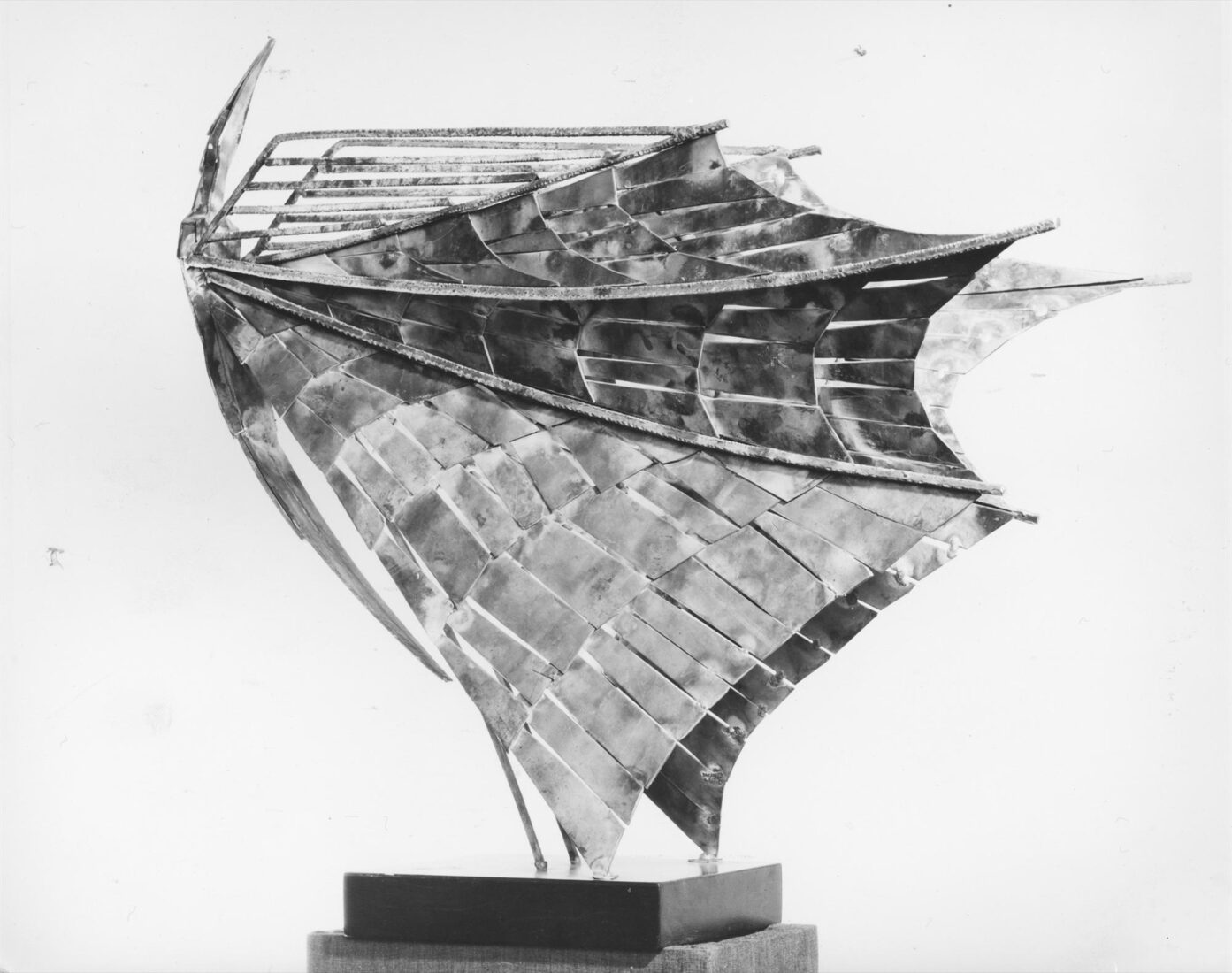

From around the end of the Fifties she started using hammered metal rods. The rods were welded together having empty spaces left between them, thus allowing space to enter the work and become a dynamic element in the composition. A “Nike” from 1960, done in hammered bronze and reshaped into practically a straight line, is an ethereal and dynamic form of the ancient image of the “Winged Victory (Nike) of Samothrace”, as it surges forward freely and impulsively and is imposed on space with the assistance of the empty space, which is spontaneously transformed into a natural background. In 1969, the rendering of movement became even freer, as the bronze rods were polished, widened and transformed into ribbons which bend and wind around empty space suggesting the body in “Nike II”, which now seems not only to be rushing ahead but to also be swirling around in a victory dance.

Frosso Efthymiadi studied ceramics in Vienna and for a long period made realistic works exclusively in terracotta. In 1955 she abandoned terracotta and turned to using metal. At this time her work became very abstract, but the physical form always remained recognizable.

The female figure sparked the creation of many small and large compositions. Sometimes static, elsewhere in motion, these pieces formulate Efthymiadi’s personal view of the harmonious rendering of female grace.

“Lot’s Wife” is her only work that portrays a religious figure. For its rendering, Efhymiadi borrowed the shape of an organic form – a tiny ordinary seashell. With this she conveyed the pure form of a woman who turned into “a pillar of salt.” The very shape of the shell offered the solution for the creation of the work, with its endless coiling and uncoiling. Schematic but totally recognizable, “Lot’s Wife”, wound in her cloak, stands petrified, motionless and silent.

The realistic and at the same time psychographic rendering of the depicted person in busts, which had already come to dominate Europe, pricked the interest of Filippotis as well, who during the period 1864-1870 was continuing his studies in Rome.

The bust of Eirene Abanopoulou, a beautiful young woman, is rendered in a practically generalized manner in regard to her nude upper chest and shoulders, which are moulded with soft curves and slight protrusions and depressions of the marble surface, but with an especially dexterous manner in the rendering of the smooth and vibrant young flesh. The sculptor’s realistic approach is expressed most clearly in the rendering of the natural features, seen in the delicate eyebrows, the pupil and iris of the eye, the fine, well-proportioned nose and the small mouth, as well as the lacy border of the dress with the low neckline. This rendering reaches its crowning point in the elaborately worked hair-style, with the long braid wound around her head like a crown.

Georgios Bonanos lived in a period of transition for modern Greek sculpture. It was a time when a number of artists had begun abandoning neoclassical styles and subject matter in favor of realism.

“Nana” is a daring composition, inspired by Emile Zola’s novel of the same name. It displays the influence of this particular literary work on Greek art as well as Bonanos’ shift towards realistic subject matter. Nonetheless, the rendition remains neoclassical. The marble surface is highly refined and the heroine is depicted nude with a tranquil face that is almost indifferent to her body’s sensual pose.

Bonanos showed this work in 1900 at the Paris Exhibition, where it won the bronze medal. In 1938 he exhibited it in the Panhellenic exhibition at the Zappeion in Athens. Bold for its time, it provoked considerable debate. At any rate, the sculptor later changed the title to “Huntress”. This change was probably due to Bonanos’ Hellenocentric ideology, but also could have been his attempt to avoid scandal. Nonetheless, the dog, the lion’s skin, and the bow and quiver associate the young woman with Artemis, Goddess of the Hunt, “mistress” and “enchantress” of animals, who here becomes the temptress of men.

Thodoros Papayannis made the human figure practically his exclusive subject, but liberated from any trite naturalistic stylization. His knowledge of ancient Greek civilization and the broader Mediterranean region, Greek folk tradition and his post-graduate studies in Paris later on, nourished, by the stimuli they offered him, the formation of his style.

Using stone, marble, bronze and clay, he gave form to his earliest, tectonic compositions, which were formed by means of geometric volumes. From around the middle of the Eighties his tendency toward ever increasing schematization has been expressed through the use of more curved lines and he has thus been led to larger-than-life-size totemic figures, references to the imposing divinities of ancient civilizations which take their form through a combination of wood, iron, polyester fibers, and various metals, as well as readymade materials that are reused.

One particular entity of his work is the series “My Phantoms”, consisting of figures tragic and at the same time repulsive, made of old wood and iron, remnants of sections of the National Technical University burned by vandals in 1994, which express the artist’s protest against violence and waste.

Thodoros Papayannis made the human figure practically his exclusive subject, but liberated from any trite naturalistic stylization. His knowledge of ancient Greek civilization and the broader Mediterranean region, Greek folk tradition and his post-graduate studies in Paris later on, nourished, by the stimuli they offered him, the formation of his style.

Using stone, marble, bronze and clay, he gave form to his earliest, tectonic compositions, which were formed by means of geometric volumes. From around the middle of the Eighties his tendency toward ever increasing schematization has been expressed through the use of more curved lines and he has thus been led to larger-than-life-size totemic figures, references to the imposing divinities of ancient civilizations which take their form through a combination of wood, iron, polyester fibers, and various metals, as well as readymade materials that are reused.

One particular entity of his work is the series “My Phantoms”, consisting of figures tragic and at the same time repulsive, made of old wood and iron, remnants of sections of the National Technical University burned by vandals in 1994, which express the artist’s protest against violence and waste.

Vally Nomidou studied painting. Her practice, however, is a combination of painting, sculpture, and environment in three-dimensional compositions crafted from all manner of material: wood, paper, plaster, paint mediums, cardboard, newspapers, and fabric. Human figures drawn from everyday life are a characteristic part of her enterprise. These figures define the space and on their own create a specific environment with minimal auxiliary attributes.

The little girl in “Bien venue” is one of Nomidou’s familiar, quotidian figures that she exhibited in Medusa Gallery in 2003. Melancholic and isolated in an invisible environment that is new and obviously unknown, the girl balances on a wooden board, the sole feature that denotes the space.

Michael Michaeledes initially worked within representational painting. Gradually his manner became more abstract, indeed becoming completely abstract by 1959. Always aspiring to capture the essence of light and to exploit the possibilities it offered for the highlighting of his compositions, he limited his use of color and along with his painting began to create reliefs and structures to be viewed from all sides, initially white and then in one or even more colors, which were composed into simple geometric shapes. In these constructions he makes use of the frame and canvas, but reverses their traditional use, as the frame functions as the interior support to which is adapted and stretched the fabric. The geometric compositions that arise from this process, repeating a shape in the same size or a gradually increasing one, are minimalist renderings of natural forms, familiar human structures or ancient architectural elements. At the same time, with the placement of the frame in the interior and the manner by which the material is stretched, even with the distance that one piece of material is placed from another, such as in “Leaning”, he manages to exploit the possibilities of light which thereby creates a host of chiaroscuros, projecting the volumes to the utmost and stressing the relief texture of the surfaces.

Theodoros very soon abandoned the representational efforts of his student years to impose his personal independent spirit on his work. He has always sought a way for sculpture to establish a close relationship with the public by creating sculptures for public spaces.

His works of the 1960s were sculptural compositions mostly in bronze or steel. He experimented with the harmony and equilibrium of forms on the ground and in the air with Surrealistic or Dadaistic prototypes as his points of departure. In this vein, in 1993, Theodoros created the construction “Twelve Ray-Spoked Wheel on Cables Counterbalanced by a Sphere”. Impressive and imposing, this construction is the only version realized in a scale appropriate for a public space. At the same time, it is a proposal for a sculpture that functions in an urban setting in the post-industrial age.